Competitive Assessment

Introduction

In both the perception of local stakeholders and visually through new and under-construction downtown developments, St. Petersburg is a city on the rise. Long-term residents often begin stories about St. Petersburg with, “if you would have seen this (fill in the blank) ten years ago, you wouldn’t believe how much it’s changed for the better.” Downtown and the waterfront are buzzing with activity and certain intown neighborhoods are seeing re-investment after years of decline. The city’s long-time economic strengths in tourism and construction are being complemented by growing concentrations in marine science, health care, professional and technical services, financial services, and the arts. But analysis of the data reveals some continuing concerns. The city of St. Petersburg and its home county of Pinellas are among the few Florida communities to have lost population in the previous ten years. Economic growth has also stagnated, even before the crippling effects of the Great Recession. The city has experienced losses in some higher-wage skills-based sectors, including information technology and manufacturing, as well as in historically strong sectors, such as retail, that presumably negatively impact city revenues. Poverty and crime remain stubbornly high and performance rates of many public school students frustratingly low. But – as symbolized by its logo “Mr. Sun” – the Sunshine City of St. Petersburg has a bright future if the momentum of its intown resurgence can continue to bolster outer districts and the gradual diversification of its economy can be accelerated. Positive signs abound in its entrepreneurial economy as an ecosystem builds around a host of key assets and skilled talent is attracted to the walkable and amenity-rich downtown. Ultimately, what many in the community would like to see is St. Petersburg better differentiate itself in the Tampa Bay area, improving prospects not only in the city but also the region as a whole. The Grow Smarter Initiative will seek to determine what makes St. Petersburg unique, how it can be developed and improved and, ultimately, how the city’s “story” can be told to potential investors and talent across the country and globe.

Overview

The St. Petersburg Area Chamber of Commerce and the City of St. Petersburg are embarking on a comprehensive process to assess and enhance the city’s competitive position to support quality, diverse economic growth now and in the future. As other cities in Florida and across the country focus more and more resources and attention on growing their economies, how St. Petersburg is positioned for quality growth is a critical issue to address. Comprehensive quantitative and qualitative research will help inform the development of a unified Grow Smarter Initiative Strategy, the culmination of an eight-month process. The Strategy will include recommendations to advance economic opportunity for all St. Petersburg residents and make the city a top destination for companies and talent. The phases of the Grow Smarter Initiative include:

COMPETITIVE ASSESSMENT

This Competitive Assessment will provide a detailed examination of St. Petersburg’s competitive position as a place to live, work, visit, and do business. Rather than simply describing data trends, the Competitive Assessment synthesizes key findings from the analysis and community input framing the discussion around key “stories” and competitive issues faced by the community. St. Petersburg trends will be compared against the cities of Durham, North Carolina; Jacksonville, Florida; and Orlando, Florida

TARGET BUSINESS ANALYSIS AND MARKETING REVIEW

Using the findings from the first phase, we often then review and define the business sectors that most strongly align with St. Petersburg’s competitive strengths. The Target Business Analysis will begin with an evaluation of the region’s workforce and then reviews existing economic strengths, global trends, and both obvious and “aspirational” job sectors. The goal of the Target Business Analysis is to identify how to diversify and strengthen the economy through entrepreneurship, existing business expansion, and recruitment. A Marketing Review will assess St. Petersburg’s principal marketing programs and tools

GROW SMARTER INITIATIVE STRATEGY

The Strategy will be holistic and inclusive of the many components that affect St. Petersburg’s ability to be a prosperous community. From business retention, expansion, and small business support to quality of life needs and educational programs that strengthen the talent pipeline, the Strategy’s ultimate goal areas, objectives, and actions would build on the findings from the research.

IMPLEMENTATION PLAN

While the Strategy represents “what” St. Petersburg needs to do, the Implementation Plan determines “how” to do it. The Implementation Plan will serve as the “road map” for putting the Strategy into motion. The Implementation Plan outlines the activities of the Strategy’s objectives on a day-by-day, month-bymonth, and year-by-year basis.

PUBLIC INPUT

Quantitative analysis in this Competitive Assessment report was supplemented by a comprehensive publicinput process. This included multiple focus groups, over 20 one-on-one interviews with top regional leaders, and an online survey available to all regional stakeholders that garnered 1,510 responses. Survey responses are provided in a separate document.

THE ST. PETERSBURG STORY

The quantitative and qualitative information gathered and analyzed for this Competitive Assessment led to the identification of certain key themes that can serve to help tell the city of St. Petersburg’s “story” in recent years. The components of this narrative not only address the community’s past, but also present questions for its future based on the identified realities, challenges, and opportunities that emerge from this assessment. In the end, the principal “takeaways” from this report will inform the subsequent phases of the Grow Smarter Initiative, ultimately leading to the development of the strategic and implementation plans themselves. The “chapters” of St. Petersburg’s story are:

- A Stagnant but Changing Population

- Returning to Residential Growth: Attractiveness to Existing and New Residents

- A Stalled but Evolving Economy

- Returning to Economic Growth: Competitiveness to Existing and New Businesses

A Stagnant but Changing Population

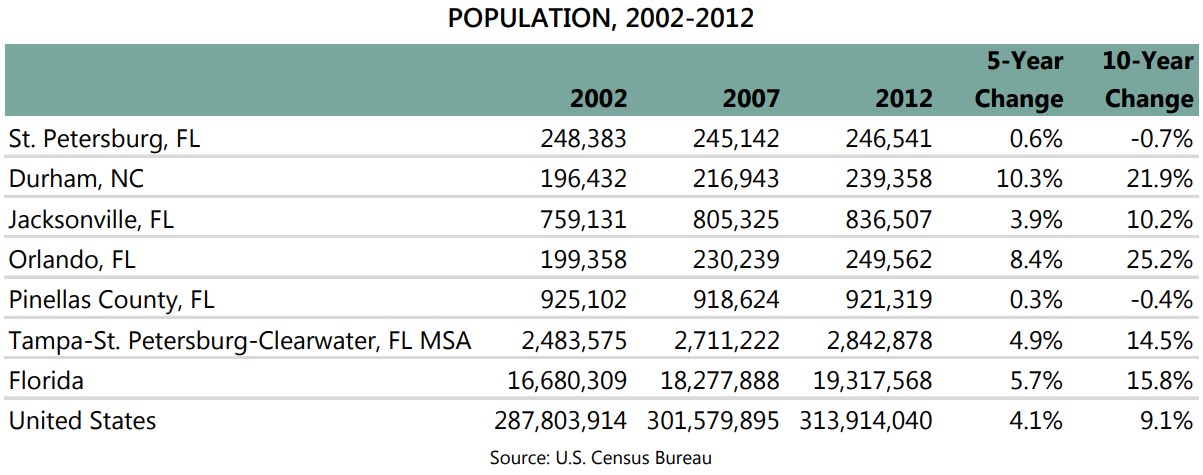

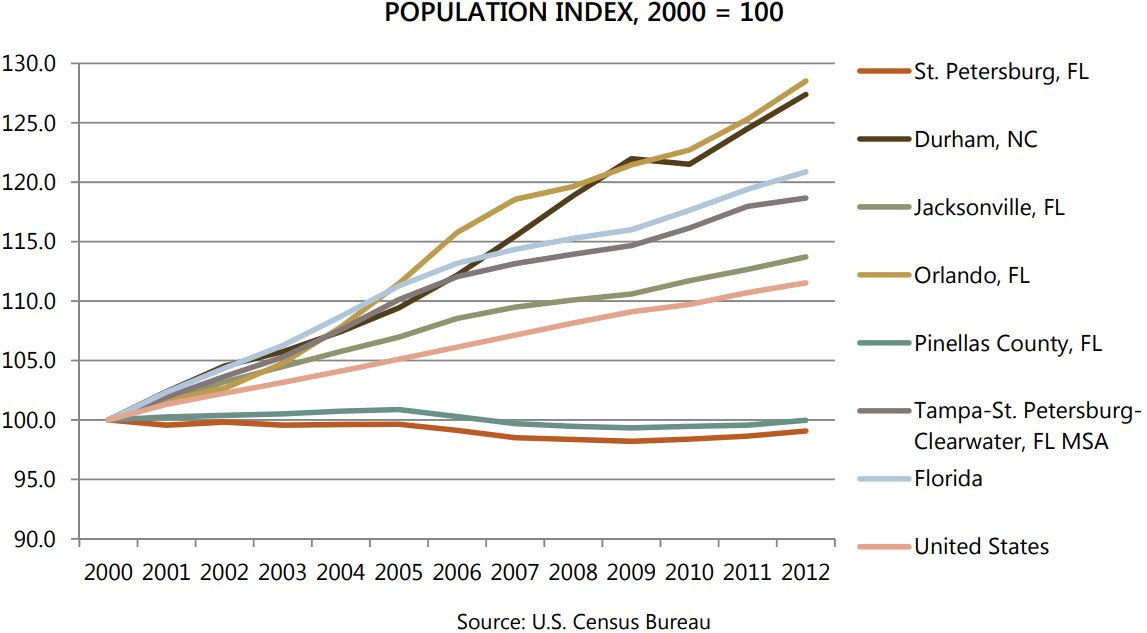

As St. Petersburg, Florida makes a gradual transition from a historical retirement destination – once pejoratively referred to as “God’s waiting room” – to a diversified economic hub, the city has experienced changes in its population dynamics, in terms of numbers and demographic makeup. Despite a highly regarded quality of life, both St. Petersburg and Pinellas County have shed residents (-0.7 percent and -0.4 percent, respectively), while all comparison geographies have experience population growth upwards of 25 percent.

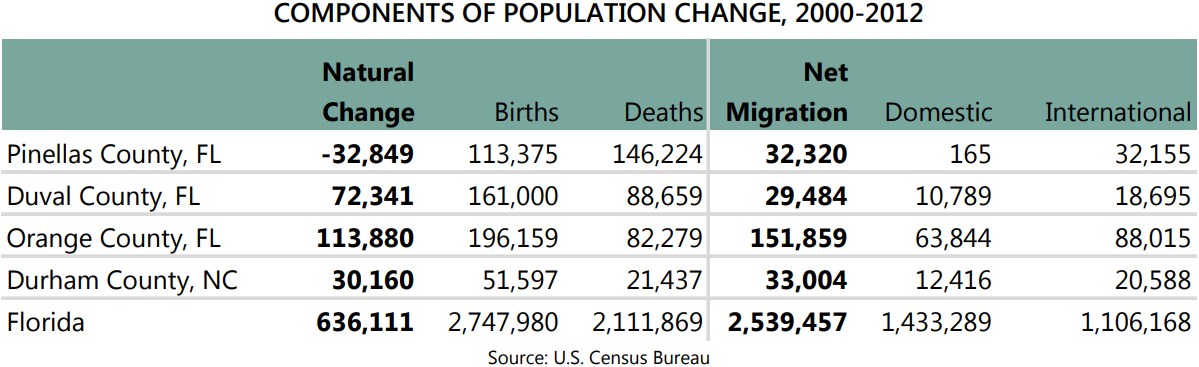

A deeper look into population components reveals that in Pinellas County, the source of population loss stems from natural change: there have been significantly more deaths than births countywide. It is worth emphasizing that Pinellas County is the only geography examined that experienced this negative natural change between 2000 and 2012

The city actually grew rapidly through the 1960s, but growth began to slow in the 1970s. St. Petersburg’s population growth has essentially been flat since 1980. The city of St. Petersburg and Pinellas County were particularly hard hit in the middle part of the 2000s. According to one input respondent, the community faced the “perfect storm” of higher property values, higher property taxes, and a steep increase in flood insurance due to the effects of Hurricane Katrina on policy rates in vulnerable coastal areas. St. Petersburg “became a place where no one could afford to live.” The next story will examine housing dynamics and other quality of life factors that influence residential choice.

As of 2012, the city of St. Petersburg’s population stood at 246,541, while Pinellas County’s population was at 921,319. With St. Petersburg comprising roughly 27 percent of the county’s total population, clearly the other Pinellas cities and unincorporated county have also seen stagnant growth. Both the previous table and the following chart starkly portray the difference between St. Petersburg’s and Pinellas’ growth curves versus this report’s comparison geographies.

Age Dynamics

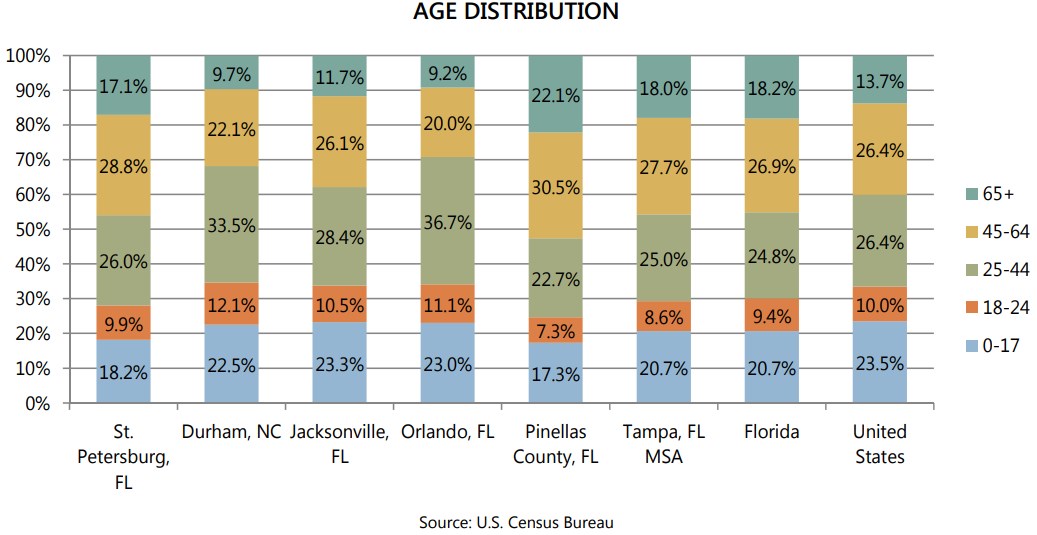

Driven by international migration, Pinellas’ impressive levels of positive net migration were not enough to overcome the effects of negative natural change, illustrated in a previous chart, which seems to reflect the community’s long history as a top retirement destination. This is reinforced by the much higher percentage of 65+ residents in St. Petersburg and Pinellas County than all the comparison areas.

Looking at the other end of the age spectrum further illustrates why natural change has been negative. St. Petersburg’s 25-44 demographic, which captures the ages where many adults are starting families with children, represents a larger share of the population than the average Florida community (26 percent versus 24.8 percent), while children under age 17 represent a relatively small share (18.2 percent vs. 20.7 percent statewide). Accordingly, this suggests that the community has a relatively low birth rate; in fact, of 67 counties, Pinellas has the 15th lowest birth rate in the state.

These trends imply that, relative to the average Florida community, St. Petersburg is either more attractive to single or married young professionals without children and/or less attractive to young families that have or plan to have children. Supporting this hypothesis is the fact that only 21.1 percent of St. Petersburg households include children, compared to 24.8 percent of Florida households and 29 percent of U.S. households. Further, the average household size in St. Petersburg is 2.27, compared to 2.62 in Florida and 2.64 nationwide.

Public input provides evidence why fewer households in St. Petersburg have children under age 17. The two biggest challenges to talent retention and attraction mentioned by multiple input respondents were housing and public schools. One interviewee said it is “tough” for families moving to St. Petersburg to find a quality three-bedroom, two-bath house. When people ask, “Where’s your executive housing?,” the respondent said, the answer is, “That’s not really St. Pete.”

In terms of schools, perceived challenges in many local K-12 campuses was said to be a disincentive to live in St. Petersburg. One former higher education administrator said that issues with public schools were the “biggest reason we lost faculty.” Other respondents noted that school costs add “another tax” if your child does not place in a desirable charter or fundamental school.

These issues and other location factors will be explored in greater detail later in this report.

Though St. Petersburg has traditionally been known as a retirement destination, perceptions and realities of the city are changing. With a dense, compact built environment conducive to walkability, a revitalized downtown and waterfront, and other place-based amenities, St. Petersburg has become an increasingly popular regional destination for young professionals (YPs).

While young professionals said in public input that the St. Petersburg YP community is “very active,” they acknowledged that the network is lacking the “sophistication” of a Washington, D.C. or Atlanta. There is a lack of engagement with the broader community and entry into the YP network still requires the individual to be proactive. “There are plenty of ways to jump right in,” one YP said, “but the perception is that it’s hard. The reality is, you just show up.” Respondents said that the multitude of YP-focused groups that have cropped up in recent years are disjointed, without a real bond between the networks.

Changing generational demographics is also leading to reported community tensions between long-time residents and newcomers with different attitudes about St. Petersburg’s future. Input residents said there’s a “difference in vision between generations.” These perspectives crop up during discussions of options for the St. Petersburg Pier, reuse of Albert Whitted Airport, and Greenlight Pinellas, among others. One interviewee said of these tensions, “We are not necessarily a ‘nimble’ community. The reality is that older people vote.” Another said that St. Petersburg is “almost Appalachian” in some ways in terms of trusting outsiders. “It’s probably generational, but it’s so hard to get things done sometimes.”

Migration

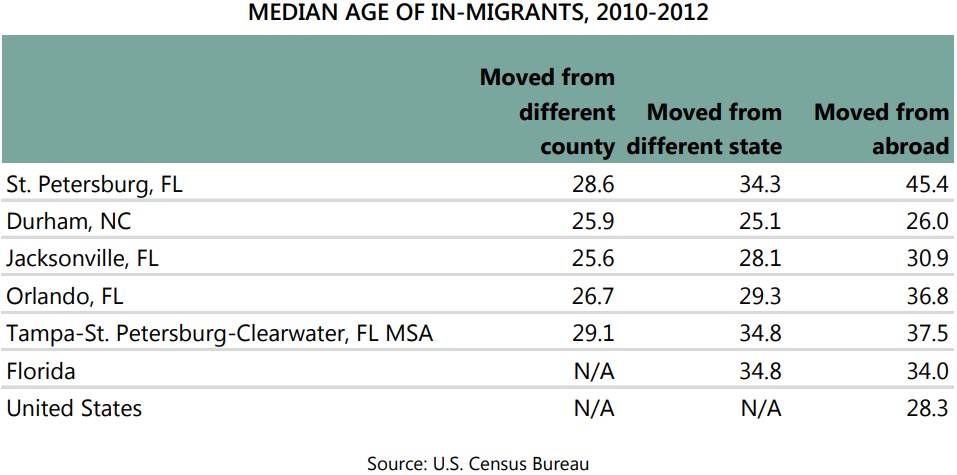

Since Pinellas County (and presumably the city of St. Petersburg) has experienced positive net migration, it is important to take a look at who is moving to the city. As the following table shows, domestic in-migrants are quite a bit younger than the city’s median age of 41.9, a major benefit to the city as it struggles with population growth due to age dynamics.

More notable is the median age of international migrants to St. Petersburg. Data are not available to determine the degree attainment of this specific group of in-migrants, but it is possible that they are drawn to the area’s mix of lifestyle amenities and expanding professional opportunities.

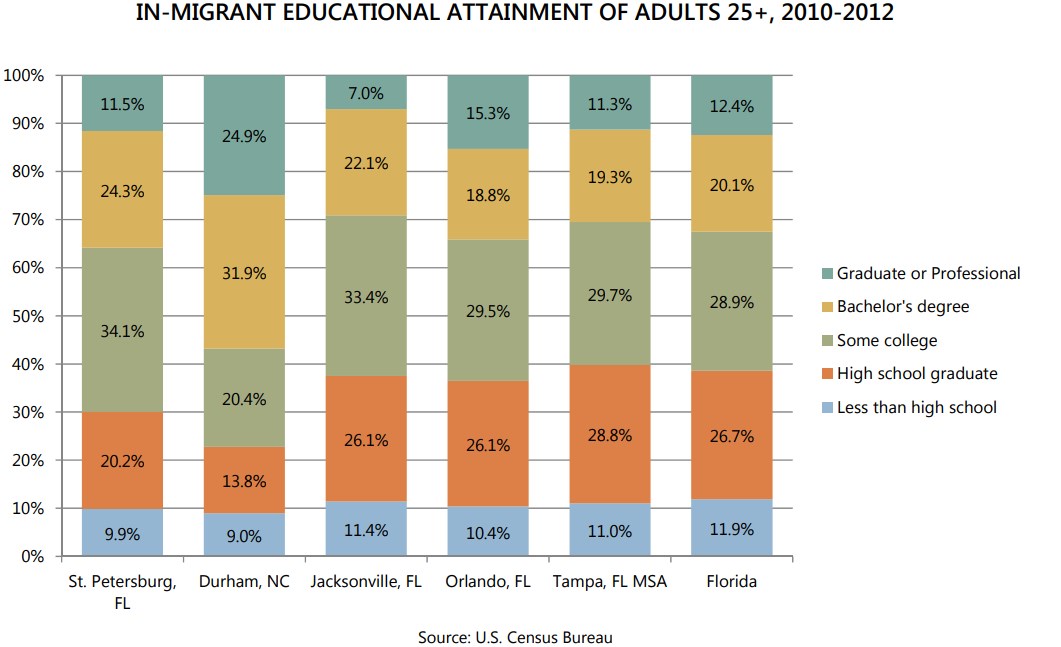

Data covering all in-migrants to the city is available, and in a very positive sign for St. Petersburg’s workforce capacity, in-migrants have higher cumulative bachelor’s degree-plus attainment than all the comparison areas except for the knowledge hub of Durham, North Carolina.

In-migrants are also slightly more diverse than the St. Petersburg average; 39.7 percent of migrants from 2010 to 2012 were minority, compared to 38.2 percent city-wide.

While detailed migration data are not available at the city level, a deeper look into Pinellas County’s foreign-born population demographics reveals that the county’s international residents are largely from Latin America (31.5 percent of all foreign-born residents of Pinellas County), Europe (31.0 percent), and Asia (23.5 percent). This is a greater level of diversity among international residents than in the Tampa MSA and the state of Florida. In Tampa, over half (53.2 percent) of its international residents are from Latin America, while in Florida three quarters are from Latin American countries.

Compared to the average resident in Pinellas, foreign-born residents are older, have a lower median household income, are slightly more likely to live in poverty, and have larger households. Foreign-born residents, as a group, are just as likely as all Pinellas County residents to hold at least a bachelor’s degree. When origins are taken into account, each subgroup has distinct characteristics. Residents who are originally from Latin America are younger but are less likely to have a four-year degree or higher, have lower median household incomes, and have higher levels of poverty. Residents originally from Europe are much older, have household sizes closer to the average countywide household size, and have the lowest poverty rate of the groups examined. Foreign-born residents from Asia have high levels of bachelor’s and graduate degree attainment, have comparatively high median household incomes, are younger than the average county resident, and also have the largest households.

Data from the Internal Revenue Service is consistent with Census data but provide more insight into recent migration patterns. Between 2006 and 2011, foreign in-migrants on average have lower household incomes ($34,385) than foreign out-migrants ($50,550). However, this is due to a large amount of highincome residents moving to another country between 2010 and 2011. In this year, the average household income of foreign out-migrants was $119,531. In other years, that figure was much lower and nearly equivalent to the incomes of foreign in-migrants. Additionally, international in-migrants during the fiveyear span had household incomes $10,000 lower than domestic in-migrants. Interestingly, household incomes of all migrants, domestic and international, were lower on average than incomes of existing residents.

An important consideration in any discussion of migration is the degree to which a community is “welcoming” of newcomers and provides access to established social and business networks. St. Petersburg’s residents, recent and long-term, overwhelmingly assert that the community is a welcoming place. Many public input respondents commented on the “Midwestern values” that continue to pervade St. Petersburg, with a strong community ethic and neighbor-helping-neighbor mentality. One interviewee recalled their first years in the city and the openness of existing residents to new professional relationships. The newcomer was “blown away by the sense of community” in St. Petersburg and noted that they were able to “make a mark” in a way inconceivable in a larger community like Chicago or New York City. “As an outsider, I was still welcomed with open arms,” they said, noting that St. Petersburg was even more open to newcomers than Tampa, where the “good old boy network is more prevalent.”

RACE AND ETHNICITY

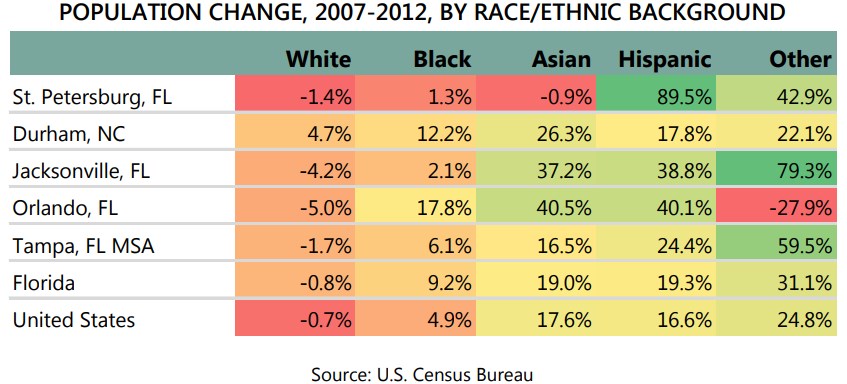

During the last decade, St. Petersburg has also diversified in terms of racial and ethnic backgrounds, consistent with national trends. From 2007 to 2012, the city experienced a 1.4 percent decline in nonHispanic whites, compared to a 0.7 percent decline nationwide. The growth in St. Petersburg’s Hispanic population was substantial—9,793 Hispanic residents were added over the five year period, or 89.5 percent growth; this represented the greatest nominal and percentage increase across all racial and ethnic groups in the city and increase eclipsed all other comparison geographies. One interesting divergence in St. Petersburg from the comparison geographies was its decline in Asian population during this period.

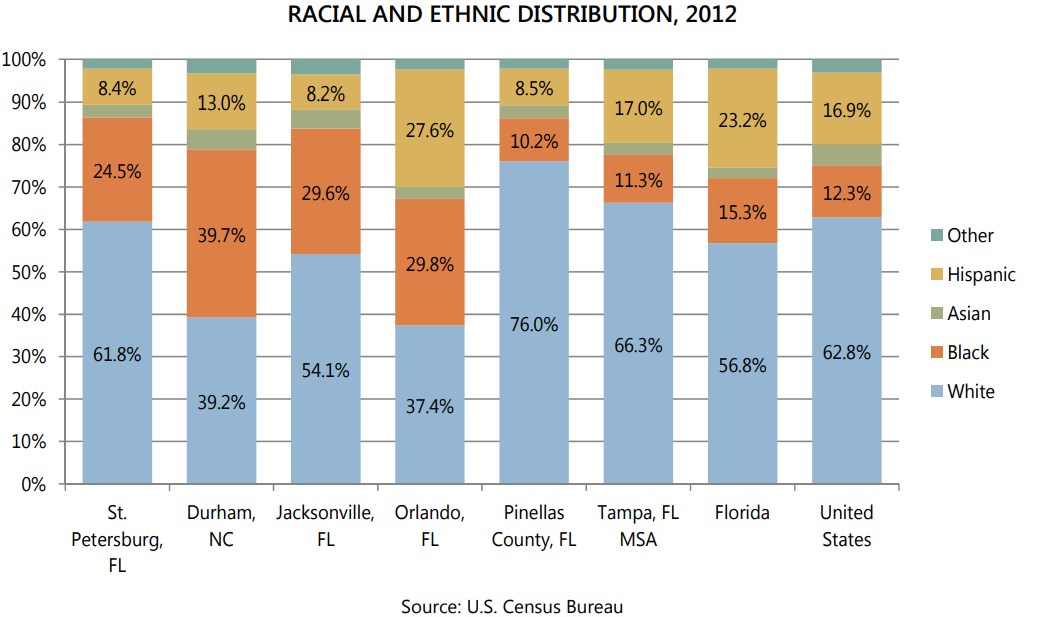

As the following chart shows, St. Petersburg, while more diverse than the Tampa metro and Pinellas County, is still significantly less diverse than its comparison cities, the state, and the nation. As the city continues to diversify, it will become increasingly important that the composition of local elected, appointed, and private leadership reflects the changing demographics of the city itself.

Despite positive feedback about St. Petersburg’s history of welcoming of newcomers, stakeholders believe that the city still must work to be more inclusive. One input participant said, “This community has never been comfortable talking about race.” Central Avenue has traditionally been the “dividing” line between black and white St. Petersburg and, despite progress in recent years, residents say some of these long-standing divisions still hold. One respondent said that some officials are “scared” at times to give feedback to minority leaders for fear of being seen as antagonistic, adding that, “We need facilitators – bridge builders.” Others said that there is still not a great deal of diversity in leadership in St. Petersburg, which leads to the perception among some outsiders that the city is “still old and white.” However, the city is changing in other ways. For example, St. Petersburg has the largest gay pride festival in the state; many credit the gay population with spurring the revitalization of the Grand Central district and other arts hubs.

When asked to rate statements on the community’s diversity and openness, on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), survey respondents collectively rated the statement “St. Petersburg is a welcoming place” as 3.99. When cross-tabbed by race, the average rating of nonwhite residents was 3.75, compared to 4.02 by non-Hispanic whites. “Opportunities, communities, and networks in St. Petersburg are accessible and open to a diverse range of people” received a much lower ranking of 3.53 overall, with whites rating this statement 3.58, and non-whites, 3.2. Residents noted the “Central Avenue invisible color line” as a persisting issue and that “more could be done to integrate and involve low income minority populations.” Another said that “the 2020 plan is a good start,” and one suggested that St. Petersburg “keep building on the inter-cultural exchanges that already exists. Keep celebrating our diverse communities more and more.”

INCOME AND POVERTY

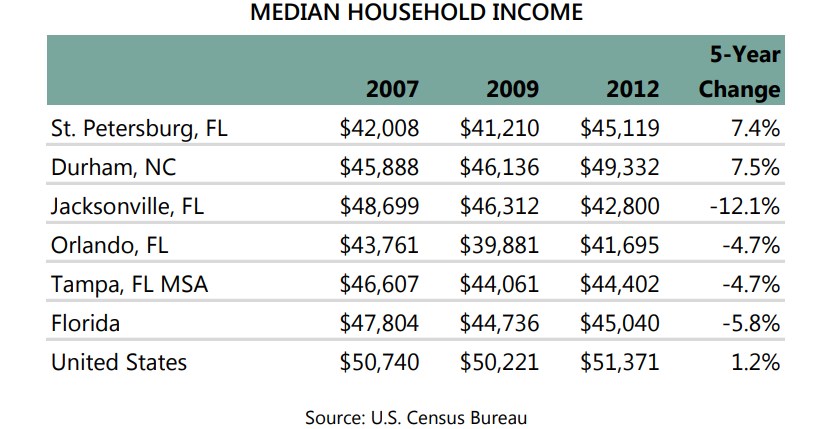

Ultimately, economic development is about creating quality jobs that serve to raise the income levels of all local residents. As such, it is important to examine the well-being of the population and how it has changed over time. As seen in the following table, changing age and racial/ethnic demographics have not had an adverse effect on St. Petersburg’s household incomes. The city’s median household income of $45,119 trailed only Durham and the U.S. among the comparison geographies. Additionally, St. Petersburg’s growth rate of 7.4 percent trailed only Durham among the comparisons. When seen in the context of the Florida geographies, St. Petersburg’s performance is even more notable. Jacksonville households saw a 12.1 percent decline in income, with Orlando and the state also experiencing losses.

When race and ethnicity are factored in, data show that St. Petersburg’s Hispanic households are doing well, with a median income of $40,814, roughly $3,000 higher than the state average. The income gap between Hispanic and white households is smaller in Pinellas than both Florida and the U.S. However, not all races and ethnicities in Pinellas are experiencing these trends. The black-white median household income gap in the county is $19,306, larger than the state of Florida ($18,182).

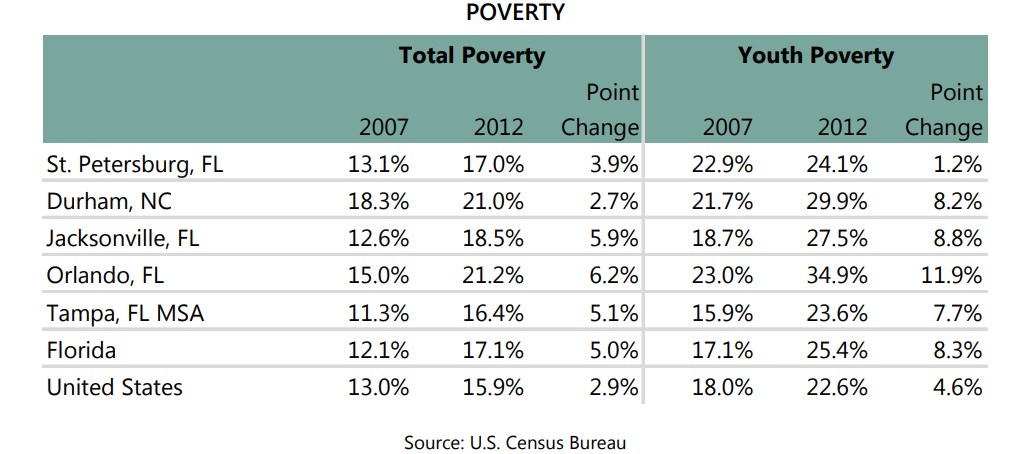

As seen in the following chart, rising incomes in St. Petersburg have kept adult and youth poverty rates below most of its comparison areas.

In 2013, the federal poverty threshold for a family of four with two children was $23,624. In St. Petersburg, 17 percent of households are in poverty, on par with the state of Florida and slightly higher than in the metro (16.4 percent) and the nation (15.9 percent). The city’s youth poverty rate (24.1 percent) has similar comparative dynamics. Despite the elevation compared to the metro and nation, St. Petersburg residents are doing well compared to its comparison cities. The city has a much lower percentage of families and youth in poverty than its peers, and its overall poverty rate has increased over a five-year period at a slower pace than Florida comparisons, partially due to St. Petersburg’s relatively small household size. There was a marginal increase in the city’s youth poverty rate from 2007 to 2012, much less than that of all comparison geographies.

In order to shed more light on poverty dynamics in St. Petersburg and Pinellas County, the County Board of Commissioners published the Economic Impact of Poverty report in 2012. A particular area of focus was South St. Petersburg, which has a poverty rate of 25 percent. The report highlights one particular Census tract in that area (245.03) that has a poverty rate of 48 percent, the second highest in Pinellas County. Overall, the report found that poverty in five high-poverty districts costs taxpayers $2.3 billion per year. A 2013 update report increased that total to $2.8 billion, while subsequent research estimated poverty costs for South St. Petersburg alone at $660 million per year.

Designed to reverse these trends, the 2020 Plan is a five-year $170 million initiative to reduce the poverty rate by 30 percent in South St. Petersburg by the 2020 Census. Set to launch in 2014, the Plan emerged from discussions and efforts from community leaders who later enlisted the support of Pinellas County and the city of St. Petersburg. In 2012, the city formalized a link between the 2020 Plan and the Southside Community Redevelopment Area (CRA) investment zone. The Southside CRA is poised to become the first new TIF district in St. Petersburg since 1992. Leaders of the 2020 effort see the CRA as a core building block of their poverty-reduction strategy. In March 2014, the Florida House and Senate appropriated $1.6 million for the 2020 Plan in the state’s next budget. However, in June 2014, Governor Rick Scott vetoed the budget recommendation despite the bipartisan support it garnered. The 2020 Task Force plans to move forward with its plan, leveraging federal funding, private foundation grants, local public funding, and private investments.

Public input participants identified generational poverty in St. Petersburg as one of the city’s most challenging issues. In many ways, one focus group participant said, “St. Pete is a tale of two cities,” with downtown and a handful of intown neighborhoods thriving and many others still struggling. The impacts of poverty were linked to challenges faced by Pinellas County schools, persistently high crime rates, poor local health outcomes in selected populations, and “food deserts” across many low-income neighborhoods.

Opinions varied on the portrayal of high-poverty neighborhoods in the local media. While some feel that progress in these districts has not been reported, others said that the magnitude of St. Petersburg’s generational poverty issue has actually been under-reported.

Poverty has also contributed to growth in St. Petersburg’s homeless population. In 2010, a Strategic Action Plan to Reduce Homelessness for Pinellas County was developed with recommendations that included, among many, coordinating and streamlining existing organizations in terms of decision-making, funding, and service delivery; improving services for families with children; and upgrading Pinellas Safe Harbor and

Pinellas Hope. Pinellas Safe Harbor is a homeless shelter designed to serve as an alternative to jail. The city of St. Petersburg has also invested much recent time, effort, and resources towards revitalization of disinvested neighborhoods, including helping to form resident and business associations, developing neighborhood plans, incentivizing the development of new retail like the January 2012 opening of a new Walmart Neighborhood Market in Midtown, and funding streetscape improvements in key corridors.

Positives

- Despite flat population change, poverty has experienced relatively slow growth during the period (2007-2012) that coincides with the Great Recession and subsequent sluggish recovery. At the same time, incomes are rising at a comparatively rapid rate. St. Petersburg also has a lower percentage of families and youth in poverty than its comparison cities.

- St. Petersburg has attracted diverse and well-educated new residents. In-migrants have higher cumulative bachelor’s degree-plus attainment than all the comparison areas except Durham, NC.

- The city is attractive to young professionals without children, as evidenced by smaller than average household sizes, low birth rates, and age distribution dynamics.

- Although overall population growth is flat due to natural change, the city of St. Petersburg enjoys a high level of international net in-migration.

- St. Petersburg is a relatively wealthy community. The city’s median household income was higher than all comparison geographies except Durham and the U.S. Incomes have grown more rapidly in the city than in its comparison geographies.

- The median Hispanic household in St. Petersburg earns more than their national counterparts. The income gap between Hispanics and white is much smaller in St. Petersburg than the state and nation.

- Residents provided resounding feedback that the city has a welcoming atmosphere, important for a place experiencing rapid diversification and high levels of in-migration.

Negatives

- The city of St. Petersburg and Pinellas County have both experienced population loss since the 1970s and are currently approaching 2000 levels. This is fueled by negative natural change, which has erased positive migration trends.

- With low birth rates, the city and county are not producing a growing number of residents who have lifelong connections to the community

- Although the average domestic in-migrant is significantly younger than the average existing resident, St. Petersburg’s in-migrants are much older than those moving to comparison cities.

- Although St. Petersburg is aging at roughly the same pace as the average American community, its average age is well above that in comparison communities, which has important implications for a broad array of issues including workforce, health and social services, and government revenues.

- Data regarding age dynamics of the community implies that St. Petersburg is not as attractive to families with children as its counterparts are, possibly reflecting the lack of confidence in public schools.

- While the city continues to diversify, its image has not kept up with reality. Although residents feel St. Petersburg is a welcoming place, they don’t feel it is as inclusive as it could be.

Returning to Residential Growth: Attractiveness to Existing and New Residents

As discussed in the previous section, while St. Petersburg’s total population has been stagnant since the 1970s, the composition of its population continues to change and diversify. This section will discuss a few of the key factors that have impacted and will continue to impact the community’s appeal to existing and prospective residents. In addition to economic conditions discussed in subsequent sections, the ability of the community to promote residential growth will depend heavily upon the community’s promotion and development of certain assets while addressing challenges that serve as residential disincentives.

Assets

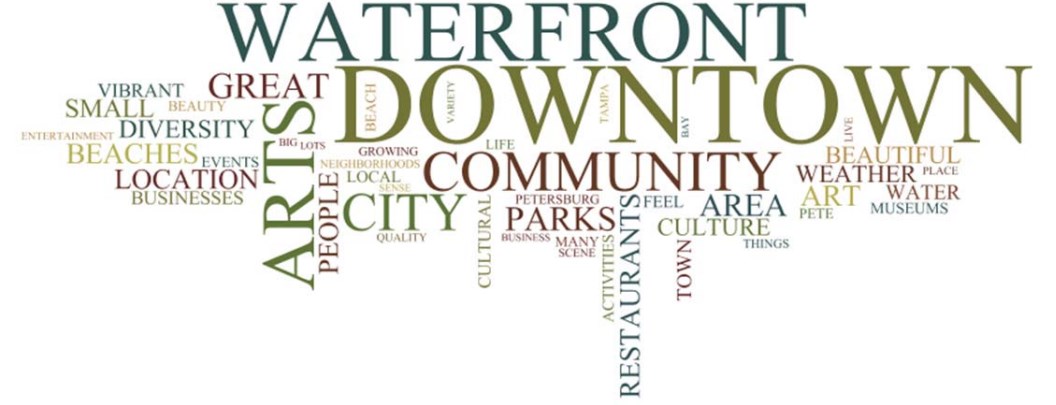

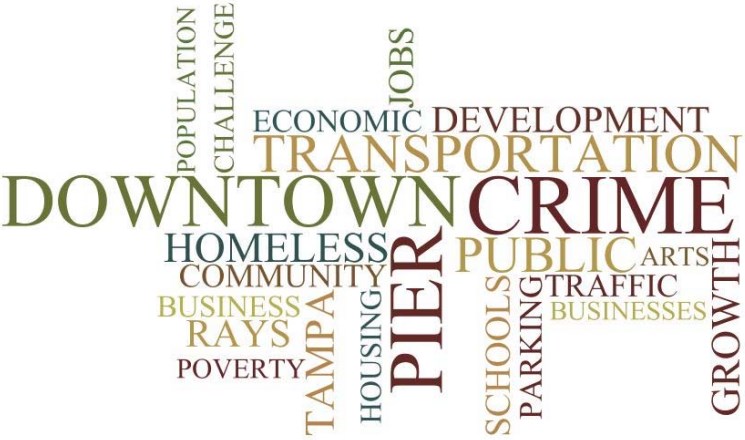

The following elements comprise key assets that contribute to the attractiveness of St. Petersburg as a residential destination. The below graphic represents a “word picture” of the most commonly used terms when community survey participants were asked, “What is St. Petersburg’s greatest strength?” Downtown St. Petersburg and the waterfront are by far considered as the city’s greatest assets, with arts also a key amenity.

Downtown St. Petersburg

As was referenced in the previous section, some St. Petersburg stakeholders view the city as “Downtown and everything else.” In only a few short years, Downtown St. Petersburg has become a thriving hub of retail, residential, entertainment, and recreation amenities and is slowly becoming the crux of the community’s entrepreneurial ecosystem. A potential innovation corridor of healthcare and marine sciences is poised for growth and cranes dot the skyline as new high-rise residential towers come out of the ground to meet growing demand for a “live, work, play” downtown environment.

The waterfront has always been seen as St. Petersburg’s greatest physical asset, serving as an anchor for industrial development in the late 1800s and early 1900s and then as the focus of the city’s beautification efforts in the 1910s and 1920s.2 The waterfront is now the location for many of the assets that makes St. Petersburg’s downtown a hotbed for growth and development: Albert Whitted Airport, the Port of St. Petersburg, plush greenspace for residents and visitors, marinas and aquariums, museums, arts amenities, University of South Florida St. Petersburg, All Children’s Hospital, Bayfront Family Health Center, St. Anthony’s Hospital, and private research firms such as SRI International.

By city charter, the bayfront cannot be developed, but the Downtown Waterfront Master Plan, currently under development, is expected to recommend planning options for sites such as Al Lang Stadium, a home for baseball spring training and international baseball, and Whitted Airport. While potentially divisive, the Plan is also anticipated to include potential re-use scenarios for the St. Petersburg Pier, the redevelopment of which has been a long-standing issue for local residents. A referendum for a new signature Pier structure was resoundingly defeated by city voters.

The St. Petersburg City Council is currently debating the merits of contracting with the planning firm AECOM for up to $500,000 to develop the Waterfront Master Plan and the planning geography that will be utilized for the analysis. The Council is slated to make its final decision on May 15, 2014. Council members would also like to see the results of an earlier development study by the Urban Land Institute incorporated into the Master Plan. The city is required to complete the Master Plan by July 2015, the result of a voterapproved referendum. The specific functionality and design of the St. Petersburg Pier will not be addressed in this master plan, however the Pier plan and the waterfront plan will be integrated and the issue is being advanced by Mayor Rick Kriseman.

Scheduled to open in spring 2014, The Sundial, a project by local businessman Bill Edwards, is a completely refurbished transformation of the former BayWalk retail/entertainment complex. Edwards has invested $40 million in the upscale shopping center with planned tenants that include Ruth’s Chris Steak House, Diamonds Direct, and White House Black Market.

One stakeholder called the revitalization of Downtown St. Petersburg, “A 25-year overnight success story.” Key catalysts included the construction of BayWalk, the redevelopment of the Vinoy Hotel and resort, and the launch of the Grand Prix of St. Petersburg. Subsequent investments in health care facilities, marine research institutions, and the University of South Florida St. Petersburg’s (USFSP) ongoing commitment to downtown were also major factors in the district’s revival. Now, leaders feel that additional meeting space, more Class-A office capacity, and business incubation facilities will help further downtown’s development into an even more dynamic mixed-use destination.

Lack of parking was also noted by input participants as a key issue. However, some acknowledge that ample parking exists but that it needs to be better promoted or connected via a wayfinding system.

Finally, while stakeholders showed excitement and support for the improvements happening in downtown, many expressed the desire to see similarly aggressive attention paid to districts outside the city center.

Another flashpoint for downtown discussion and controversy is the future of the Tampa Bay Rays in St. Petersburg. Though they have a use agreement to play at Tropicana Field until 2027, the team has expressed the desire to relocate to a new stadium either in the city or across the bay in Tampa. Even those who support the Rays remaining in St. Petersburg say that the opportunities to develop the 86-acre Tropicana Field site are enticing, especially because it abuts the assets of a potential innovation corridor. With St. Petersburg’s and the TDC’s debt obligations fulfilled at Tropicana Field in two years, interest groups are positioning themselves to claim the tourism dollars that will be freed up for other uses.

Arts and Culture

Known as the “City of the Arts,” St. Petersburg has a long history of supporting arts and culture as a key component of its tourism-development strategies. The city was the site of the first art gallery south of Atlanta and was the first Florida city to organize its museums. Currently, St. Petersburg is known for its concentration of blown-glass artists and benefits from the presence of dozens of top-ranked galleries, several theatrical and music venues, many world-famous museums, seven performing arts companies, and over 1,000 public events annually. Five distinct arts districts are located in the city, including Grand Central and the Warehouse Arts District. In 2013, ArtPlace America named Downtown St. Petersburg one of America’s top ArtPlaces. For three years running, American Style Magazine has named St. Petersburg as its number one mid-size city for art. The New York Times included the city on a list of 52 global places to go in 2014, while British newspaper The Independent reported that St. Petersburg now rivals Miami as an arts destination.

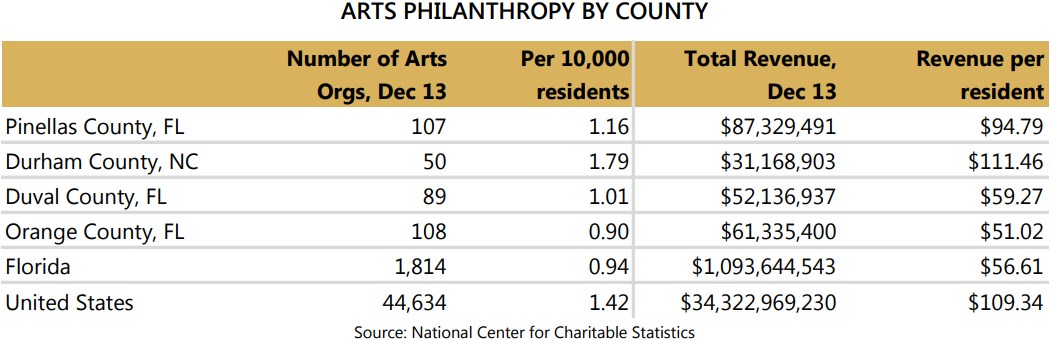

As the following table shows, non-profit Pinellas County arts organizations are numerous and receive comparatively high levels of support from philanthropists. Only Durham and the U.S. had higher per capita numbers of arts organizations and revenue per resident.

Stakeholders in the arts community expressed concern in public input that St. Petersburg’s competitive advantage in the arts is at risk due to a lack of public and private support. One participant noted that everyone in the arts world is “hanging on by the fingernails. We need businesses to step up and support us.” Another added, “The city is building its reputation on the back of artists,” but the sector is not being funded. According to arts officials, six local galleries have moved to other cities in the last four to five months. Ultimately, said one stakeholder, “artists need more arts buyers, and that comes from promotion.”

Another obstacle, according to input participants, is St. Petersburg’s “complicated minefield of little arts groups” that makes it hard to organize and focus the constituent base.

Recently, the Tampa Tribune reported that a newly formed alliance of arts organizations called the PinArts Coalition is demanding that Pinellas County restore funding that was cut during the recession. At one point, the now defunct Pinellas County Cultural Affairs Council provided $600,000 in annual grants to local arts organizations, while the Tourist Development Council (TDC) delivered $750,000 in bed tax dollars each year. PinArts would like to see $1.5 million in county and TDC money dedicated to arts and culture and the creation of a $150,000 “artist resource fund.” It is also calling for the City of St. Petersburg to return the amount available for arts grants to prerecession levels. City funding for local arts grants fell from $400,000 to $175,000 in 2008 and has not been increased.

Walkability

Communities are beginning to understand that

walkability is a multi-generational desire. Walkable places

feature destinations like grocery stores, restaurants,

entertainment, retail, green space, and other amenities

that can be accessed by foot on one trip. Research has

shown that the Millennial generation is partial to

communities with options beyond cars for getting

around and that some actively seek places to live that

provide ample alternatives to driving, such as public

transportation, ride sharing, and car sharing. Also

applicable is the growing research showing that seniors

value walkability in communities to help them maintain a

healthy, active lifestyle and access to services beyond

their driving days. More and more people, irrespective of

age, enjoy easy access to “third places”—a place they can

go for social interaction outside of home and work.

Communities are beginning to understand that

walkability is a multi-generational desire. Walkable places

feature destinations like grocery stores, restaurants,

entertainment, retail, green space, and other amenities

that can be accessed by foot on one trip. Research has

shown that the Millennial generation is partial to

communities with options beyond cars for getting

around and that some actively seek places to live that

provide ample alternatives to driving, such as public

transportation, ride sharing, and car sharing. Also

applicable is the growing research showing that seniors

value walkability in communities to help them maintain a

healthy, active lifestyle and access to services beyond

their driving days. More and more people, irrespective of

age, enjoy easy access to “third places”—a place they can

go for social interaction outside of home and work.

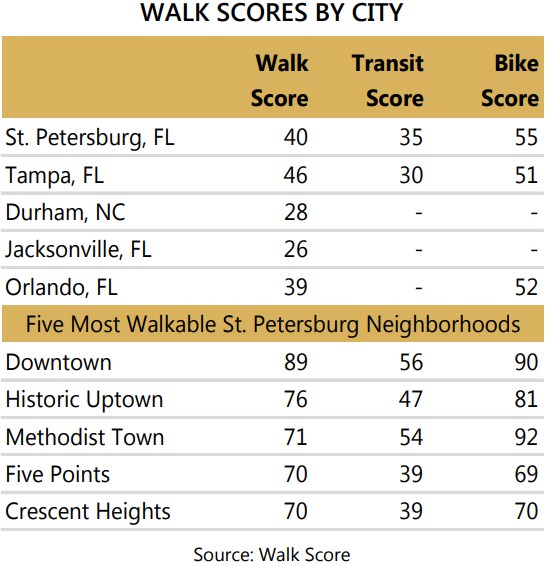

The table above shows that the Tampa Bay area has a competitive advantage in terms of walkability compared to the other cities profiled in this report. Downtown and Historic Uptown St. Petersburg are especially competitive in this regard. Although St. Petersburg’s bike score is higher than Orlando and Tampa, the score is relatively low on a national comparison. The City Trails program is approximately 10 years old and has been improving the city’s bike score. , St. Petersburg’s relatively low scores on transit and biking capacity show that there is much work to be done to enable true multi-modal mobility in the city.

Even though Shermans Travel named St. Petersburg one of its top ten cities for cycling because of its 35 miles of bike trails, 75 miles of on-street bike lanes, and status as a bronze-level Bicycle Friendly City by the League of American Bicyclists since 2006, stakeholders would like to see enhanced bike lanes and trails, including wider lanes and more off-street biking infrastructure.

A key initiative that would potentially increase St. Petersburg’s transit score is Greenlight Pinellas, a mass transit referendum scheduled for a public vote in fall 2014. The Greenlight Pinellas Plan includes bus improvements and future passenger rail that supporters say would significantly enhance public transportation in Pinellas County. The plan would be funded by a proposed 1 percent sales tax increase and would be implemented over span of 30 years. Components of the plan include:

- A 65 percent increase in overall bus service throughout Pinellas County

- Bus Rapid Transit lines on most major Pinellas corridors.

- Buses running to and from Tampa and the airport in the evenings and on weekends

- Longer service hours to accommodate second shift workers and evening travelers

- Light Rail – 24 miles

- Future passenger rail from St. Petersburg to Clearwater via the Gateway/Carillon area

Multiple public and private officials speaking in public input identified Greenlight Pinellas as a potential “game changer” for St. Petersburg. In addition to improving rail and bus transit capacity and connectivity, the opportunities for transit-oriented development (TOD) and the creation of activity and job centers around stations could be transformative for the city and complement its already high density and walkability. Though the initiative is supported almost unanimously by business and civic associations on both sides of the Bay, officials fear that perceived burdens caused by increased sales taxes could sway public opinion against the measure. Current polls show that a majority of likely voters support Greenlight Pinellas.

The following pages comprise key challenges to raising St. Petersburg’s population levels as identified by research and public input. The below graphic represents the terms most used by community survey respondents when asked about St. Petersburg’s “greatest threat or challenge” to overcome. Crime, homelessness, transportation, the Pier, and housing were among the top challenges identified. Downtown, a top asset, was also a top challenge, likely because of public safety and homelessness issues.

CHALLENGES

The following pages comprise key challenges to raising St. Petersburg’s population levels as identified by research and public input. The below graphic represents the terms most used by community survey respondents when asked about St. Petersburg’s “greatest threat or challenge” to overcome. Crime, homelessness, transportation, the Pier, and housing were among the top challenges identified. Downtown, a top asset, was also a top challenge, likely because of public safety and homelessness issues.

Land Capacity

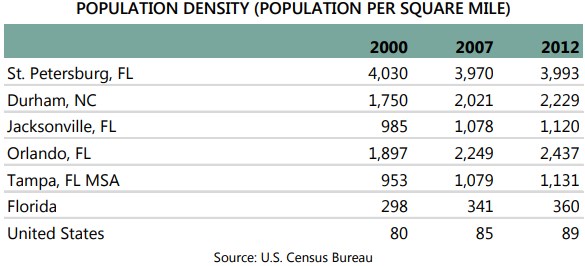

Though it is a misnomer that St. Petersburg is “built out,” as many people allege, it is true that there are few if any major “greenfield” sites available for development, either residential, retail, office, or industrial. This notion is validated by the data in the following table showing the comparative densities of St. Petersburg and the benchmarks. While the comparison areas have become denser in recent years, St. Petersburg is still by far the densest of these geographies. The city has nearly 4,000 people per square mile and has likely not shown the increases in density of the comparison areas because of factors possibly including residential abandonment due to the foreclosure crisis, limited redevelopment and high-rise infill construction due to the effects of the Great Recession, and the plain fact that there is not a lot of land for new construction.

With seven CRAs, three with available TIF, and other tools, Pinellas County and the city of St. Petersburg feature a number of programs supporting neighborhood revitalization, redevelopment and infill construction.

Public officials say that the city and county are still coming to grips with the “new normal” of postrecession Pinellas. Governments are looking at opportunities for regeneration and adjusting landuse and zoning controls accordingly. Future land-use plans are being reexamined not only in the context of redevelopment but also to capture potential opportunities related to Greenlight Pinellas passage and the continuing spread of development pressures outward from Downtown St. Petersburg into the downtown’s close-in neighborhoods.

Housing

As was noted, along with perception of school quality, the top issue constraining St. Petersburg’s future growth identified by stakeholders is the quality of the city’s housing stock. There are over 1,000 condo and apartment units currently under construction in Downtown St. Petersburg, with plans for an array of price points, to accommodate the demand for housing in the thriving area. However, the need for detached homes, both to purchase and to rent, with enough square footage, bedrooms, and bathrooms to satisfy growing families is a pressing concern for city officials, and is consistent with the earlier finding that St. Petersburg is not currently attracting young families with children. The city’s historic attractiveness as a retirement destination led to the construction of thousands of “2+1” concrete block homes-on-slab sufficient for the needs of middle-income retirees but inadequate for the demands of modern couples and families. More condos and apartments reinforce current dynamics, and housing diversification is necessary if St. Petersburg wants to increase its attractiveness to families. Because of the lack of land capacity, building new detached homes is not a viable solution—revitalization and renovation of existing homes will be key.

Young professionals and entrepreneurs commented on the unavailability of nice, affordable housing in St. Petersburg, stating that newer homes in favorable neighborhoods are unattainable pricewise and that affordable homes were either located in neighborhoods they are uncomfortable moving to or needed too much rehabilitation work.

The Venture House project seeks to address this deficit and revitalize neighborhoods at the same time by leveraging a combination of private and public funds and “sweat equity” to transform dilapidated homes into residences that can attract entrepreneurial and artistic talent from the region and elsewhere into St. Petersburg’s core. Venture House is spearheaded by Frank Wells, who uses a community land trust model to hold properties and connect buyers with resources to purchase and rehab the homes.

The quantity of available homes in St. Petersburg increased after the recession as more residents in the city turned to rental housing from 2007 to 2012. While consistent with trends across the state and country, St. Petersburg experienced a larger percentage decline in home-ownership than all the comparison areas, from 66.0 to 57.6 percent.

In addition to challenges homebuyers face due to tightening credit markets, another major issue affecting whether individuals can retain or purchase homes is the dramatic increase in flood-insurance premiums. When the Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act took effect on October 1, 2013, homeowners saw insurance rates increase by 20 percent per year or more. Partial relief is on the way as a new federal bill, known as the Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act, recently signed into law keeps rates from climbing more than 15 percent annually and institutes a hard cap of 18 percent. The bill goes into effect on May 1, 2014, and homeowners should see the new rates reflected in their insurance premiums when they renew their policies. While primary homeowners will likely see benefits, businesses and second-home buyers will not see significant reductions in their insurance bills.

Public Safety

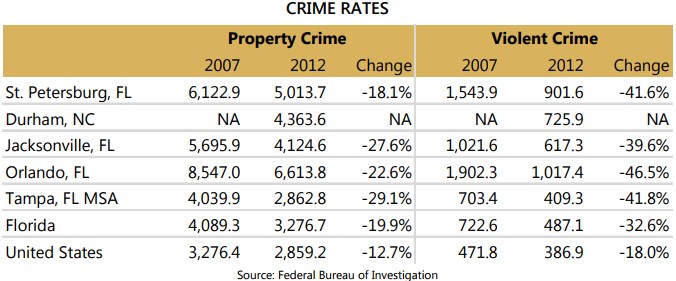

Public safety is a critical component of a community’s quality of life. Dynamics of crime typically involve two elements: the reality of crime and the perception of crime. Each is important because perception is the equivalent of reality for most residents and businesses. Data reveals that crime is on the decline in St. Petersburg. However, crime is very high in the city and considerably higher than the metro average. Despite this, the Tampa Bay metropolitan statistical area (MSA) has relatively low crime as compared to other Florida metros.

In a very positive sign, violent crime in St. Petersburg has decreased over time at a rate on par with the metro and at a higher pace than the state and nation. It is also important to note that while Orlando experienced a higher percent decrease in violent crime, its 2012 rate is still the highest among all geographies. Unlike violent crime rates, property crime in St. Petersburg has not declined at a competitive rate; its improvement lags behind comparison cities, the metro, and the state. As St. Petersburg attempts to reverse its population outflows, persistent issues of crime are a significant barrier to attracting and retaining households, especially families with children.

Survey respondents were asked to name St. Petersburg’s greatest threat or challenge to overcome. Among the top answers was crime. When asked “If you will not continue to live in the community, and/or feel your children will not choose to live in the community, why do you feel this way?” one respondent answered “I am not sure it is a safe place to raise children.” Sense of personal and property safety was among the lowest rated quality of life aspects, garnering an average response of 3.2 of 5 total points.

Public Education

One significant challenge to St. Petersburg’s quality of life is the perceived quality of Pinellas County public schools. As noted in the previous storyline, public education was said to be a major deterrent to residing in St. Petersburg for young families with children or who plan to have children.

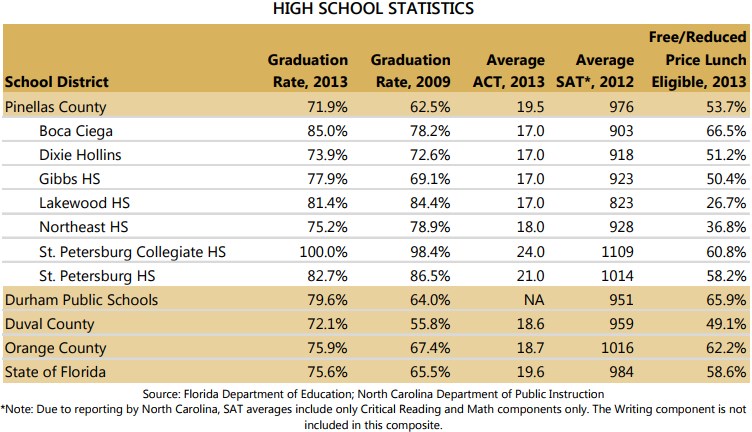

On the face of the issue, Pinellas County performance measures such as SAT and ACT scores are roughly equivalent to the Florida state average, while graduation rates are just slightly lower. Compared to the districts of comparison communities, Pinellas County has low four-year cohort graduation rates, though ACT scores are higher than in Florida peer counties and SAT scores are higher than two of three comparisons. Coupled with lower child poverty and “teenage idleness” rates than the comparison areas, a lower percentage of Pinellas students are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch – considered a proxy for determining low-income student totals for comparisons across states. In fact, when compared to districts in the comparison communities, only Duval County, Florida has a lower percentage of free and reduced-price eligible students. These common measures of exposure to “at-risk” conditions do not seem in line with public perception that Pinellas County Schools are an option of “last resort” for many families.

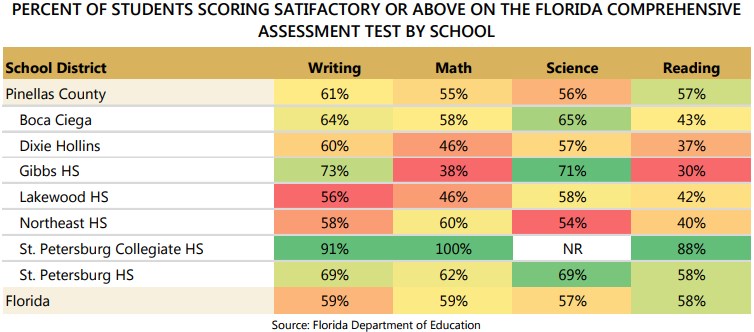

When the high schools in St. Petersburg are examined, data continues to contradict the perception that the city’s schools are challenged. Only three of the seven high schools in St. Petersburg have a greater proportion of students eligible for free or reduced price lunch than the county average. Although college readiness exam scores are on average lower in St. Petersburg high schools than the county, graduation rates for all high schools in the city surpass the county average. This fact is counter to the feedback of many who said the Pinellas schools outside St. Petersburg perform better. Additionally, when Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test (FCAT) scores are taken into account, there are clear stars in St. Petersburg’s public district. Consistent with higher standardized college entrance exam scores, St. Petersburg Collegiate High School and St. Petersburg High School have higher percentages across all subjects of students scoring satisfactory or higher on the FCAT. This is generally true for students at these schools by racial group and for students who are considered economically disadvantaged as well. Gibbs students are strong in Writing and Science, but weak in Math and Reading with economically disadvantaged students trailing school averages by 11 percent and 10 percent, respectively. While the remaining schools do have bright spots in varying subjects, five of the seven high schools in the city have low percentages of students performing well in Reading.

In 2013, the Pinellas County district was graded a C by the Florida Department of Education, which is based on a number of factors including reading, mathematics, science, and writing assessment scores and improvements from previous years. Only one high school in the district scored less than an A or B, and that school was not located in St. Petersburg. Boca Ciega, Lakewood, St. Petersburg High, and St. Petersburg Collegiate High are among the Pinellas high schools earning As. However, this is a new achievement; from 2012 to 2013, schools earning C scores were upgraded to Bs. In 2010, two St. Pete high schools earned Ds. As the school district continues to make valuable changes that result in better performance results, these accomplishments will need to be promoted in order to avoid persistent negative perceptions of improvement trends that may not be entirely valid.

More insight is gleaned in elementary and middle schools. Of the elementary schools located in the city, 11 earned A or B, 7 earned a C, and 8 earned D or F. Unfortunately, many of the low scoring middle schools are located in St. Petersburg. Of the seven middle schools in the city, only one, Thurgood Marshall Fundamental School, scored an A. Two earned Cs, and the rest earned D or F. It is important to note, though, that there are many other elementary and middle schools outside of the city of St. Petersburg that have earned low scores. Nevertheless, parents may choose communities outside the city of St. Petersburg in these grades if these trends continue.

While it is evident that St. Petersburg schools have challenges in some areas, the data does not support the notion that St. Petersburg schools are not competitive with the rest of the district, and parents do have access to a wide range of school models. Alternative campuses include magnet programs, career academies, and fundamental schools. There are also independent schools, charter schools, and traditional private and parochial schools in the city. The curricula and structure of these schools vary.

Additionally, the business community has close ties with the district. Through a partnership with Ford Next Generation Learning and the Florida Association of Career and Technical Educators, the school district has begun implementation of its Academies of Pinellas Five Year Master Plan, which has resulted in a career academy at every high school in Pinellas County guided by industry specific advisory councils. The career sectors represented in St. Pete high schools include finance, information technology, automotive, and graphic arts. Lakewood High School has a marine sciences program in its Academy for Aquatic Management Systems and Environmental Technology.

The Pinellas district also has a mentoring program for students called Executive P.A.S.S. (Partnership to Advance Student Success), involving several area businesses such as Raymond James, through which CEOs along with their employees assist with mentoring students and providing administrators with business perspectives. As the district continues to make strides in providing quality educational opportunities for Pinellas County students and realize subsequent improvements in performance measures, it will need to ensure that residents know about these advancements and that they are happening districtwide, including in St. Petersburg.

Multiple stakeholders indicated that newcomers to the region with school-age children are encouraged to choose Tampa over St. Petersburg because of the difference in quality of schools. Also per stakeholder input, Pinellas County Schools is not the preferred choice for parents in St. Petersburg, unless they are able to win the lottery for the district’s fundamental schools. When commenting on alternative Pinellas campuses, one input respondent said that lower income students are “left behind in regular school.” Participants said there is a “clear border” that divides north and south Pinellas County in terms of perception of school quality with north county schools considered strong and south county’s seen as poor.

Focus group participants added that community and parental involvement is often lacking in Pinellas schools, as are effective mentoring programs for students. Some said that a lack of resources and “lack of will” to make significant changes in the district are also challenges.

Survey respondents were asked to rate various statements about public school quality. “Children in our district receive a high-quality education” received the lowest rating, with a score 2.69 of 5 total points. Career guidance and hands-on work experiences received a rating of 2.93, while the commitment of community and business leaders received 3.03. Among the higher rated (yet still low) statements were opportunities for parental involvement (3.88), available and affordable pre-K programs (3.46), and committed and engaged teachers (3.46).

Positives

- Rapid transformation of Downtown St. Petersburg in recent years is a point of pride for the community. Its “live, work, play” environment has attracted many new residents, while there are several opportunities for business expansion, attraction, and innovation within the corridor.

- St. Petersburg’s vibrant arts community includes world-renowned attractions and has been featured in major publications for its assets. Pinellas County has numerous non-profit arts organizations which receive competitive levels of support from philanthropists.

- St. Petersburg’s walkability is attractive to both the young workers it needs to develop a sustainable workforce and the older retirees who will become decreasingly reliant on cars over their lifetimes.

- Greenlight Pinellas promises to be a game changer for the community if passed this year. There are several enhancements within the plan that will address the connectivity needs that stakeholders have expressed.

- Pinellas County and the city of St. Petersburg feature a number of tools and programs supporting neighborhood revitalization, redevelopment and infill construction.

- Although public perception of schools is mixed, the Pinellas County school district and St. Petersburg campuses have competitive bright spots and are making strides in improving performance results and creating and maintaining meaningful relationships with businesses in the community.

Negatives

- Although the city has seen major declines in recent years, St. Petersburg still has high crime rates and issues of homelessness, which can be residential deterrents to both existing residents and potential new residents

- Lack of business support, lack of government funding, and disconnected arts organizations are among the issues that the arts community has identified as threats.

- Although downtown St. Petersburg will soon have over 1,000 rental and condo units available, the city has single-family detached housing stock that needs to be revitalized to help the city attract families, especially as limited land is available for new construction.

- Public schools are not the preferred option for parents in St. Petersburg and suffer from key perception issues. Residents do not seem to be aware of the improvements that are happening in the public system.

A Stalled but Evolving Economy

Similar to St. Petersburg’s population decline, the city’s economic fortunes in the past decade have not been laudable. Though home to major corporations, large hospitals, a burgeoning entrepreneurial sector, a legacy tourism economy, and one of the strongest concentrations of marine sciences employment in the southeast, the city’s employment numbers paint a dimmer picture than one would imagine from these assets. This section examines St. Petersburg’s recent economic trends and looks at the underlying structure of local employment.

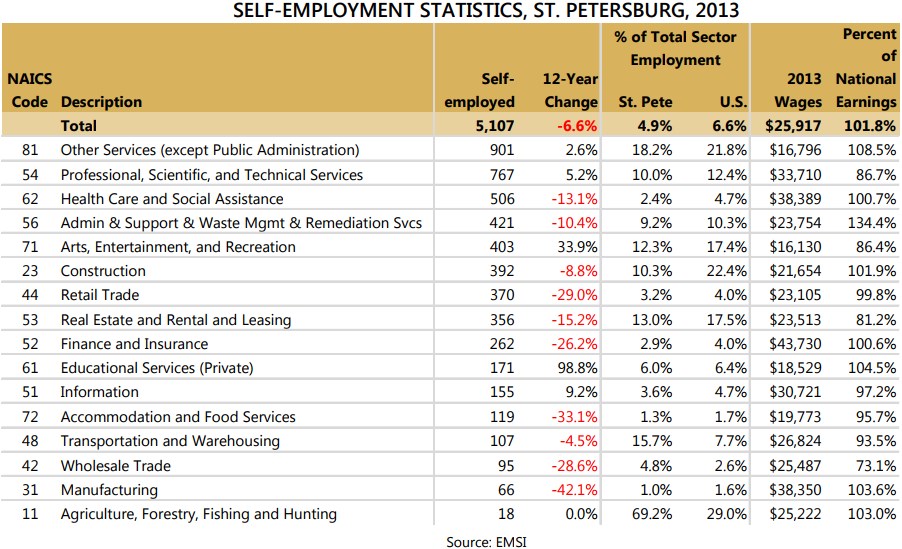

EMPLOYMENT

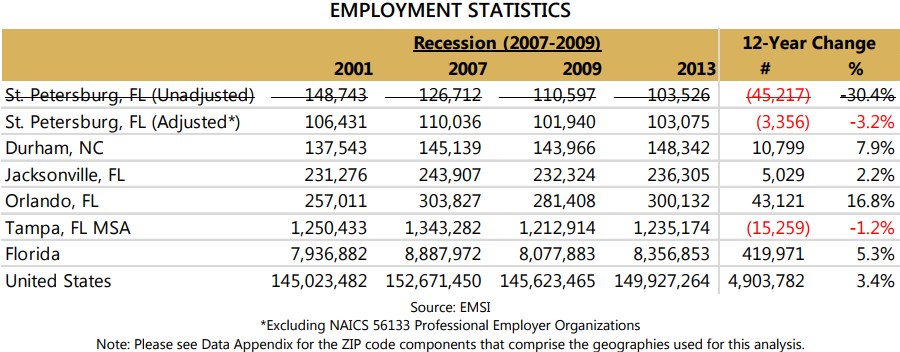

When examining trends in employment since the start of the new millennium, it appears – at first glance – that St. Petersburg has lost a considerable number of jobs in recent years. In fact, the data show that the city shed more than 44,000 jobs from 2001 to 2013, equivalent to roughly 30 percent of its total employment base. However, the reality is that these employment numbers are severely misrepresenting the true employment situation in St. Petersburg.

When examining these reported employment losses in greater detail, it is evident that the overwhelming majority – more than 42,000 – were attributed to job losses among professional employer organizations (PEOs) that provide human resource management services to businesses. These organizations work much like staffing agencies in that the employee is physically located at the worksite of the client business but is technically employed by the PEO. Thus, PEO employees are counted in the home office’s location even if they are working in another city, county, or even state in some instances. So in fact, the losses attributed to PEOs located in St. Petersburg are likely widely dispersed across the state and country; very simply, the reported job losses occurred at establishments whose staffing is managed by a PEO located in St. Petersburg.

When PEOs – the source of this misrepresentation – are excluded from total employment figures, the employment situation looks much less severe. Even so, St. Petersburg still suffered considerable employment losses over a 12-year period from 2001 to 2013. More than 3,300 jobs were lost in the city, equivalent to 3.2 percent of total employment. While St. Petersburg contains roughly eight percent of all jobs in the metropolitan area, it accounted for roughly 22 percent of all job losses in the metropolitan area from 2001 to 2013. During the Great Recession (2007 – 2009), the city lost nearly 8,100 jobs, a rate of decline (-7.4 percent) that exceeded the rate of recessionary employment losses experienced in the three comparison communities, but that trailed the rate of recessionary employment loss observed across the metropolitan area (-9.7 percent) and the state of Florida (-9.1 percent). However, while the city’s recessionary downswing was not quite as severe as that which was experienced regionally or across the state, its recovery has been more sluggish. Since 2009, the city has recouped just 1,135 of the nearly 8,100 jobs shed the recession, or roughly 14 percent. All comparison communities have recouped at least 34 percent of recessionary employment losses, while the national economy has recouped 61 percent of all jobs shed during the Great Recession.

Taken together, these trends illustrate that St. Petersburg is a community whose true employment situation may be mischaracterized by publicly available and proprietary data sources. However, it is also a community that – even when adjusting for these sources of misrepresentation – is still struggling to emerge from the Great Recession, much like the rest of the metropolitan area. As a result, it has fallen behind in the competition for jobs in the new millennium; while St. Petersburg has lost three percent of its jobs since 2001, the cities of Durham, Jacksonville, and Orlando have experienced rates of job growth between two and 17 percent since 2001.

Founded as a tourism-based economy, the city of St. Petersburg has been sustained over decades by business sectors focused on welcoming travelers and providing them with amenities and entertainment. As the Tampa Bay region grew, the city of Tampa became the “production” town (most famously through the manufacture of cigars), while St. Petersburg focused on services. Certainly, there was, and continues to be, a manufacturing presence in St. Petersburg, but the city has increasingly become a location for multiple service sectors running the gamut from health care to financial to “big data” and home shopping.

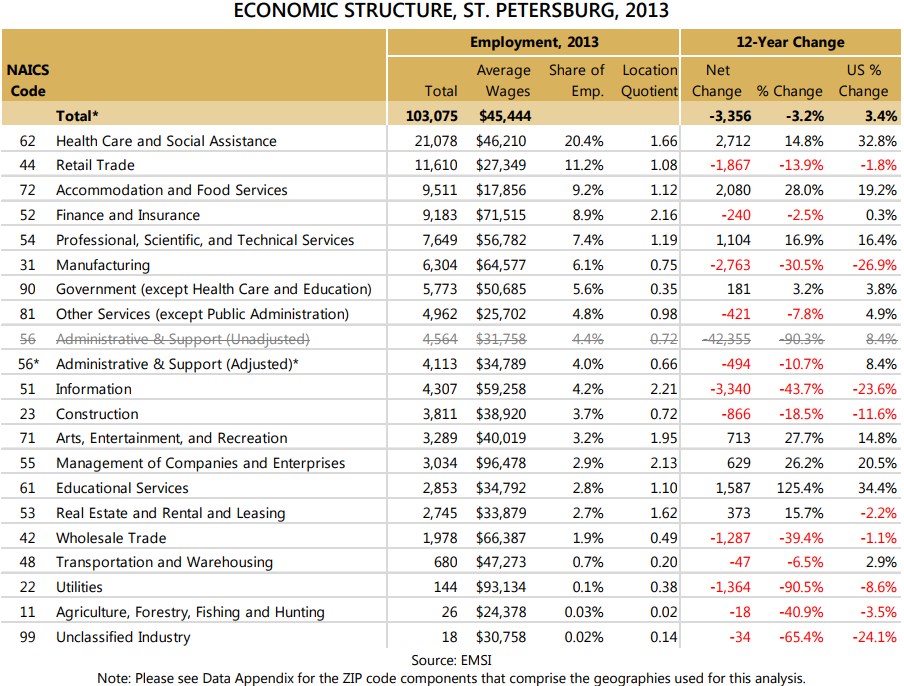

Over the 12-year period examined, St. Petersburg has experienced job growth in higher-wage, knowledgebased sectors such as professional, scientific, and technical services; management of companies and enterprises; and health care and social assistance, which are all existing strengths in the city with the presence of major corporations and headquarters. Over the same period, however, the city has lost many jobs in technical and goods producing sectors. It is important to note, though, that not all of these jobs are lower-wage—manufacturing and wholesale trade provide very competitive average wages. Additionally, the city has experienced a decrease in information services and finance and insurance, two important existing strengths, while increasing lower-wage accommodation and food services jobs. Utilities have likewise decreased over time. In 2011, the Tampa Bay Times reported that Duke Energy employed approximately 400 workers in its St. Petersburg location.5 Losses since that time are likely due to the 2012 merger with Duke Energy. Losses in the information sector included the restructuring of the St. Petersburg Times, which led to layoffs starting in 2003, and losses in finance and insurance included widespread layoffs of firms, including Allstate Insurance, Branch Banking & Trust, Mortgage Investors Corporation, and Transamerica Life Insurance.

Location quotients (LQs) are a commonly-used measure for evaluating the composition of a local or regional economy. Location quotients measure the relative concentration of a given sector in a local economy – as measured by its share of total employment – relative to the national average for that same sector. If a location quotient is greater than 1.0 for a given sector, the community has a larger share of employment in that sector than the nation, indicating that such economic activities are more heavily concentrated in that community than the average American community. Firms operating in sectors that are highly concentrated in a given regional often “cluster” because there is some competitive advantage to be derived from that geographic location. Such advantages could include an abundance of a specific labor pool, proximity to key natural assets, or proximity to infrastructure needs such as a port or intermodal terminal, among many other potential advantages.

Location quotients reveal some areas of historical strength for St. Petersburg, most notably its legacy sectors of Retail Trade (LQ=1.08), Accommodation and Food Services (LQ=1.12), Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation (LQ=1.95), and Real Estate and Rental and Leasing (LQ=1.62) that are heavily tied to the tourism economy. The community is also home to a strong concentration of more knowledge-based sectors such as Finance and Insurance; Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services; and Management of Companies (Corporate Headquarters). Health Care and Social Assistance is not only the city’s largest employment sector by nearly 10,000 jobs, but is also considerably more concentrated in St. Petersburg than the average American community. Health care services – particularly major hospital systems – are typically concentrated in more urban areas; accordingly, some level of concentration of health care services in St. Petersburg is to be expected. However, at roughly 20 percent of all local employment, health care’s immense economic impact cannot be overlooked.

Many of St. Petersburg’s most concentrated sectors are consistent with the city’s largest employers. Raymond James Financial is headquartered in St. Pete and provides investment and financial planning, investment banking, and asset management to its clients. All Children’s Hospital, located in downtown St. Peterburg, is the only specialty licensed and freestanding children’s hospital on Florida’s west coast and is now in the Johns Hopkins network. Bayfront Health St. Petersburg, located in the same district as All Children’s, is a teaching hospital that has a 15-county medical emergency and trauma helicopter program. The Home Shopping Network – categorized an NAICS 51 Information – is a $3.3 billion firm, while Jabil , which manufactures products and develops supply chain strategies for electronics and technology companies, is a multi-national powerhouse with strengths across multiple sectors.

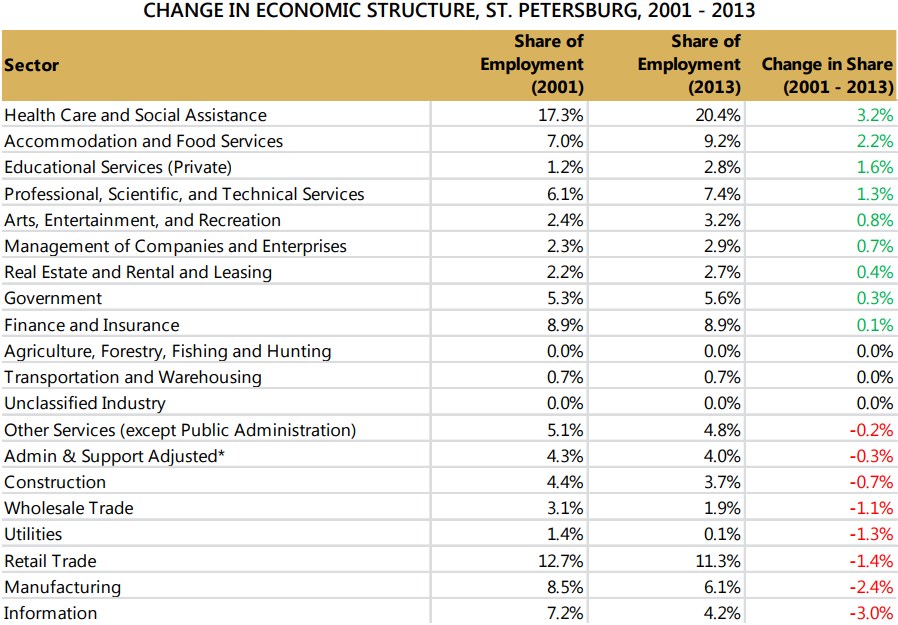

Between 2001 and 2013, a period during which the city lost nearly 3,400 jobs or three percent of its employment base, the community experienced considerable change in its economic structure.

With a few exceptions, the city is very clearly moving towards a more knowledge-based, serviceoriented economy. During the 12-year period, the city shed roughly 4,100 jobs in sectors related to goods production and distribution (manufacturing, transportation and warehousing, and wholesale trade). Those jobs were replaced by a roughly equal gain of nearly 4,300 jobs in health care and social assistance. Given the widespread misperceptions that most manufacturing and distribution-related jobs are low-skill and thus low-wage, many would misperceive this shift away from goods-production and towards health care services as a movement from lower-wage to higher-wage jobs. And while health care is a relatively knowledge-intensive sector with many occupations that pay well above the community’s average wage, the reality is that the average wage for all positions in the manufacturing, transportation and warehousing, and wholesale trade sectors exceeds the average wage across the health care sector.

Certain segments of the community’s tourism-related economy have held up well and strengthened over time. The accommodation and food service (hotels and restaurants) and the arts, entertainment, and recreation sectors have added nearly 2.800 jobs since 2001, increasing their collective share of total city employment form 9.4 percent to 12.4 percent. However, the retail sector – which often tracks closely with the accommodation and food service sector – has shed nearly 1,900 jobs. Although most retail jobs are relatively low-wage, retail sales are an important source of revenues for many local governments. Accordingly, any precipitous decline in retail employment is likely to be accompanied by a corresponding decline in sales tax revenues

When looking at other areas of historical strength for St. Petersburg that are commonly associated with a more knowledge-based, service-oriented economy, it is evident that professional and technical services (including accounting, legal, engineering, research and development, etc.) and the management of companies (corporate headquarters) have become more heavily concentrated while information services (software publishing, data processing and hosting, etc.) has declined considerably.

Overall, the community has experienced a transition that has resulted in the elimination of many jobs associated with goods production and distribution, and the gain of jobs in more knowledge-oriented service sectors. However, there are some important exceptions – most notably the significant decline experienced in information services. The community has shed jobs in some lower-wage sectors associated with travel and tourism, such as retail trade, but added equal numbers in even lower-wage sectors such as accommodation and food service. It has added jobs in the higher-wage professional services and corporate headquarters sectors but shed even more in the higher-wage information services and finance sectors.

But across all sectors, average wages have expanded rapidly in Pinellas County. Given the aforementioned observations regarding change in composition by sector, it is clear that much of this wage growth cannot be attributed to changing economic composition (shifting away from lower-wage jobs to higher-wage jobs); rather, it must largely be attributed to organic growth within sectors. Very simply, employees are experiencing upward mobility in terms of wages at a rate that exceeds that which has been enjoyed by their peers in the comparison communities.

Public input participants were most bullish about St. Petersburg’s opportunities in emerging sectors like “big data” and also its potential to cultivate and leverage a downtown “innovation corridor” spanning employment concentrations in health care and marine science as well as the presence of the University of South Florida St. Petersburg campus. While estimates of the total number of marine science workers and PhDs located at the city’s port varied, there was agreement that St. Petersburg’s marine science industry is one of the most concentrated in the southeast United States and even the nation. With ten agencies, hundreds of PhDs, and $1 billion in infrastructure, the cluster can potentially be economically transformative with the proper support, stakeholders said. This includes opportunities to site research vessels at the port, expand the capacity of USF’s College of Marine Science, and leverage potential synergies between oceanographic research and health sciences innovation at the corridor’s medical establishments. A potential challenge related to expanding a research presence at the Port of St. Petersburg is a ten-year maximum lease period for entities located in the district. A previous referendum to extend the lease term was defeated. More specific data on the city’s economic structure will be included in the Grow Smarter Target Business Analysis.

Bolstering St. Petersburg’s reputation in the marine sciences is the city’s pending hosting of the Blue Ocean Film Festival. Reaching approximately 20,000 filmmakers and scientists and exhibiting film and photography projects by popular media outlets including National Geographic and the Smithsonian Channel, the week-long film festival is one of the largest global environmental documentary film events.

Many stakeholders expressed hope that during this festival, strategic dinners and tours will be employed to develop relationships and stimulate continued interest in St. Petersburg as a prime location for marine sciences.

Opportunities to grow high-value St. Petersburg employment sectors will be examined in much greater detail in the Grow Smarter Initiative Target Business Analysis report, the next deliverable in the planning process.

In the next storyline, we will look at some of the factors that can impact St. Petersburg’s continuing evolution into a more diversified, knowledge-based economy.

Positives

- Wages in St. Petersburg are rising at a rate that exceeds the rate of growth observed in all comparison areas.

- The city has seen job gains in high-paying, knowledge-based sectors such as private health care and social assistance; professional, scientific, and technical services; and management of companies and enterprises (corporate headquarters).

- Tourism-related sectors such as accomodation and food service, and arts, entertainment, and recreation have added jobs since 2001 in St. Petersburg at a pace that significantly exceeds the national rate of expansion.

- Sub-sector data show that job losses in the city are not nearly as significant as what is reported by commonly-cited publicly available and properitary data sources.

Negatives

- St. Petersburg has struggled to emerge from the Great Recession, having recouped a small percentage of the jobs lost between 2007 and 2009.

- The city has shed jobs in some of its areas of historical strength, most notably finance and insurance, and information services.

- St. Petersburg has lost nearly 2,800 manufacturing jobs since 2001, declining at a rate that slightly exceeds the national loss.

- Although it is positive that overall job losses in St. Petersburg are heavily overstated, the misperceptions of these trends could lead observers to make false conclusions about the health of the city’s economy.

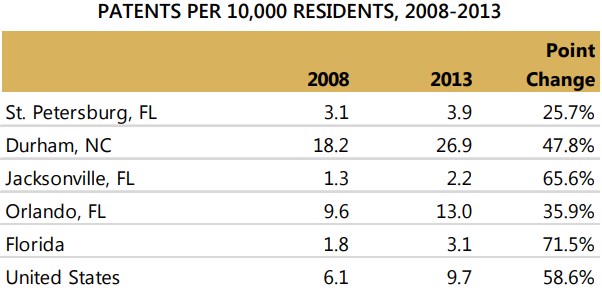

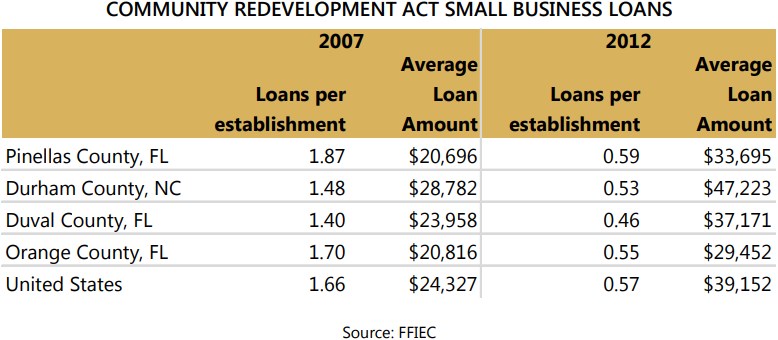

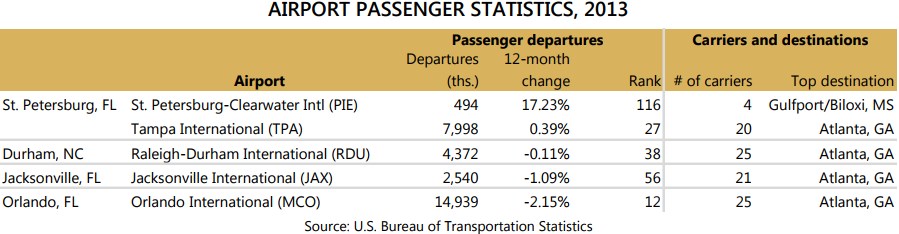

Returning to Economic Growth: Competitiveness to Existing and New Businesses

Many U.S. communities are actively pursuing more “21st Century” knowledge-based jobs; the transition that St. Petersburg is experiencing is positive on the surface, but only if the city can stay abreast and even ahead of the competition. This will require a balanced, targeted, and strategic approach to identifying, nurturing, and leveraging the pressure points that will move St. Petersburg’s technology economy forward. This storyline examines some of the most important elements of this transition.

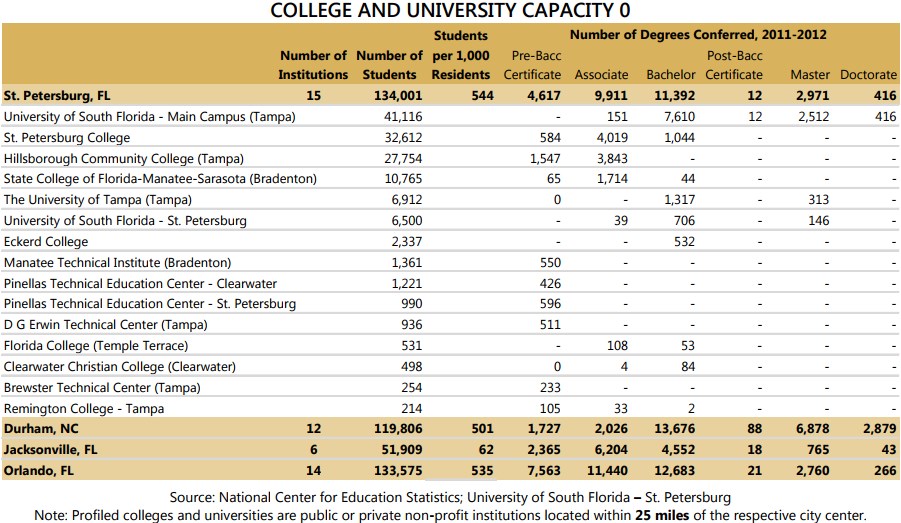

A COMPETITIVE WORKFORCE

Nothing is more important in today’s economy than the skill level of a community’s workforce. It is what technology-focused companies are looking for and they will locate in the places that offer not only the talent to grow their operations but also a training pipeline ensuring that that talent base is sustainable. Transitioning a workforce like St. Petersburg’s from a commodity services model to a technologically sophisticated, knowledge-based model will require time, patience, investment, leadership, perspective, and drive. But the building blocks are there in the thousands of existing technology jobs and steadily evolving entrepreneurial ecosystem in the city.

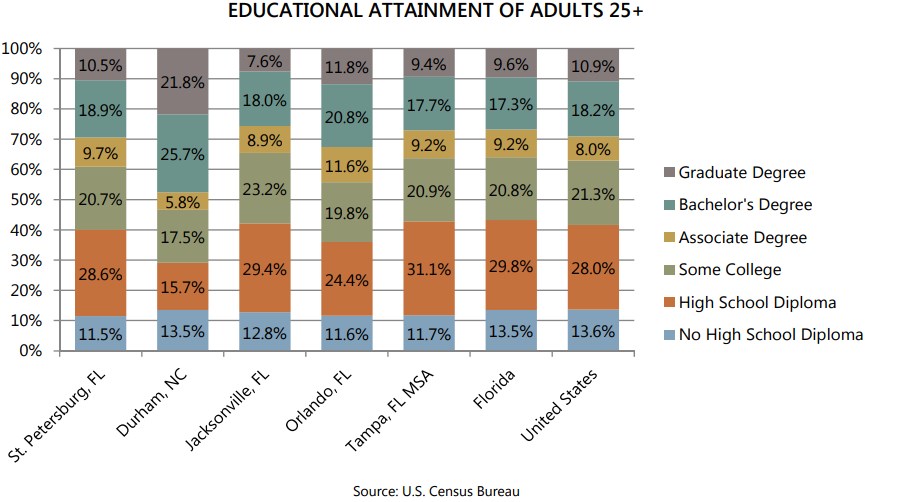

Workforce Skills

Educational attainment – or the percentage of adults with a Bachelor’s degree or above – is a key indicator of a community’s workforce skill capacity. In knowledge-intensive regions, this percentage is often upwards of 40 percent of the adult population. While the percentage of adults aged 25 and older in St. Petersburg with a Bachelor’s or higher is on par with the national average, the Tampa Bay metro’s rates are slightly lower. In fact, of 366 metros in U.S., the Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater MSA ranks number 158 for adults aged 25 and over with at least a college degree. What this means is that in order to compete for future knowledge-intensive jobs with some of the country’s most talent-rich metros, St. Petersburg will have to import talent from outside the region and improve the retention of local college graduates.