Episode 055

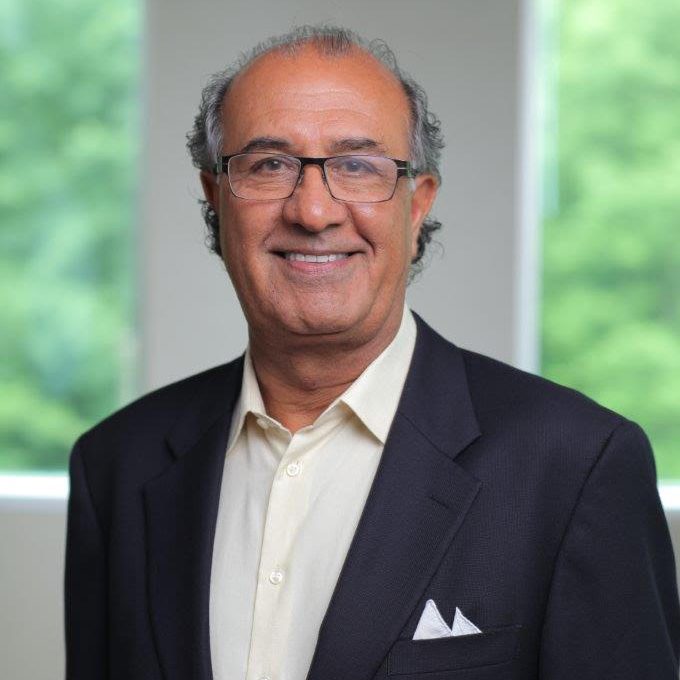

Iqbal Paroo, Paroo & Associates

The fascinating life of Iqbal Paroo: How an accident led to an epiphany - and a 45-year career

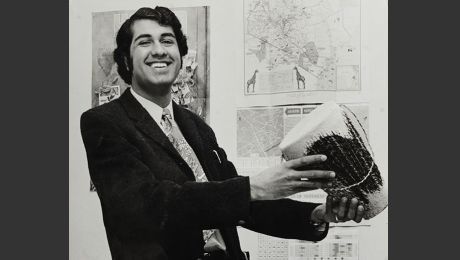

On this episode of SPx, our host Joe Hamilton is joined in studio by the unparalleled Iqbal Paroo. There are few people in this world with a life story as inspiring as Paroo's. From his childhood in colonial Kenya to his time in the Kenyan air force, to the traumatic injury that changed the course of his life, Paroo has packed three lifetimes into one. He shares his story, his professional trajectory and how he made his way to St. Pete. Paroo talks becoming a hospital CEO at 25, and president of a university at 37, raising capital as an entrepreneurship and how race shaped his experience in the United States.

Key Insights

- On this episode of SPx: Iqbal Paroo. From colonial Kenya to St. Petersburg, Paroo shares his long career in healthcare and healthcare consulting, with caveats in higher education and nonprofit work along the way.

- Paroo lost his leg in a motorcycle accident at age 17. During the recovery process, he became interested in how healthcare was delivered and how such a large organization was run.

- Paroo asked to speak with the hospital superintendent and became deeply interested in study healthcare administration. That superintendent pushed him to study in the United States.

- Paroo received a scholarship to Georgia State University through NSAID, he became a finance major and also considered pursuing medicine.

- As a junior in college, Paroo began running all of the business operations for a hospital. At 25, he became a hospital administrator for a hospital in Biloxi, Mississippi.

- Eventually, Paroo's mother would send his 13 year old sister to live with him. "I assumed a lot of responsibility at a young age," Paroo said. "I think between how I grew up and the responsibilities that I took on all lead me to develop certain skillsets about dealing with things and people and issues."

- After Paroo's initial stint in healthcare, he felt a calling to return to his roots: "There was a calling for me to go back. So, I hadn't gone back to Kenya, but I was ready to go back to a developing country to deploy the skills and the experiences I had gained to go build something that would benefit that part of the world for a long time to come."

- Higher education: Paroo spent 2-3 years at Hubbard Hospital at Meharry Medical College, attempting to turn the historically black medical school around. He successfully lobbied the Reagan administration to continue funding the school, despite Reagan's blanket order to end funding.

- Paroo talks about what it was like to be a young person of color in the United States at that time, especially one who didn't fit into the binaries of black and white.

- Paroo shares how he obtained funding from one of New York's largest equity funds, Warburg Pincus, and how that helped him launch his healthcare company Qualitas.

- Following his work with eBay founder Pierre Omidyar's foundation, in 2008 Paroo and his wife moved back to her hometown, St. Petersburg, where they continue to live more than a decade later.

- Paroo now serves as managing partner of Paroo & Associates, where he has advised large companies like Johns Hopkins, Atlantic Health, Emory University and Emory Health.

- Paroo was also appointed by President Obama to the African Development Foundation. To this day, Paroo travels to African 3-4 times per year for two weeks at time.

- "I'm working hard to level the playing field. I work hard in things that would give people who lack opportunity access to opportunity to create the enabling conditions and environment for people. I do it in Africa, I'm doing it here too in my own ways."

- Paroo's shoutouts: The Florida Orchestra, The St. Pete Free Clinic, USF St. Petersburg's Martin Tadlock, and the Open Partnership Education Network.

"I label myself as a humanist, I consider myself a world citizen, literally. I'm U.S. citizen, but I'm a world citizen."

" I achieved my success in this country, I worked hard for it, but I achieved it here and he told me that at some point no matter who you were or what your background was, what your color was, what your faith was, you could achieve."

Iqbal Paroo Speech from Alumni Association on Vimeo.

Table of Contents

(00:00 to 00:54) Introduction

(00:54 to 03:50) Starting Out

(03:50 to 05:30) Iqbal’s Accident

(05:30 to 08:20) Iqbal’s Epiphany

(08:20 to 10:19) Pursuing The Medical Profession

(10:19 to 13:12) Working Together And Relying On Others

(13:12 to 14:10) Journey Through School

(14:10 to 15:42 ) The Family Business

(15:42 to 20:34) Becoming a Hospital Administrator

(20:34 to 22:41) Being a Young Leader

(22:41 to 24:55) Being A Leader In Different Hospitals

(24:55 to 27:15) Calling To Karachi

(27:15 to 28:21) Coming Back To The United States

(28:21 to 30:22) The Evolving Healthcare Business

(30:22 to 36:05) Experiencing Racial Divide

(36:05 to 39:30) Preventing Distress Funding Loss

(39:30 to 47:30) Iqbal’s Later Career

(47:30 to 48:39) Being a Consultant to John Hopkins

(48:39 to 49:45) African Development Foundation

(49:45 to 52:13) Wealth Disparity

(52:13 to 55:15) Politics In The Field

(55:15 to 59:04) Conclusion

Full Transcript:

Joe: Joining me on SPx is Iqbal Paroo, welcome sir.

Iqbal: Thank you for having me.

Joe: You have a very interesting life and I’m excited to dig into it. I guess what you would consider your sort of core profession is a boutique consulting effort in the medicine space, can you tell us a little bit about that?

Iqbal: Yes, so I actually call it in the healthcare space which would include medicine and it comes out of a very long career that I’ve had in healthcare from my early days in the undergraduate when I was an undergraduate I worked in a nursing home just to supplement income while I was on a scholarship. And there is a whole story behind how I got into healthcare because I was born and raised in Kenya and was in the Kenyan air force training as a pilot. And one weekend I had an accident and lost my leg above the knee – my left leg was amputated. And while I was recovering I began to think about, well, I knew I wasn’t going to be able to fly again, so I said, ‘What am I going to do?’ And was just intrigued with my own recovery process and the healthcare being practiced around me. But you’ve got to remember it was 1967 in Kenya so the medicine was pretty basic and yet it saved my life.

[00:02:17]

And an epiphany came to me which was to sort of think about healthcare medicine as a space I could pursue. And I was a very strong student, and I was very strong in the sciences. I also grew up in a family where I was exposed to a lot of business, I had a business sense to me. So, I said wow, I could combine all of this and potentially pursue healthcare. And that’s what ended up bringing me to the U.S. I got a scholarship through USAID to come to the U.S. and that took me on a long path. I was the youngest administrator of a hospital in a company, I was only 25 and I became an administrator of a hospital. By 37 I was president of Hahnemann University in Philadelphia which is a health sciences university. And in between I’ve done many, many things and running larger hospitals, help build a campus in Karachi, Pakistan for the Aga Khan Foundation. I had run and done a turnaround of Meharry Medical College in Nashville. So, I was deeply, deeply steeped in the healthcare space. And then I’ve done many other things in my career, but finally 10 years ago I decided to stop being the Chief Executive of a large organization, whatever it was, because I had also run a foundation for a few years. I set up a boutique consulting practice and so that’s what I do now.

Joe: Well, there’s a lot in there. Let’s go back to Kenya.

Iqbal: Yes.

Joe: So, you had the accident when you were…?

Iqbal: I was 17.

Joe: Can you talk about the accident?

[00:04:00]

Iqbal: Yeah, so I was on a motorcycle with friends on a weekend because as I said I was in flight training in the air force and I had the weekend off so I was on a motorcycle and was hit by a car being driven by an elderly lady who was coming out of her driveway and she failed to stop, she just entered the main road which I was on, and so were my friends. And she hit me, I think from what I understand she panicked and when she hit me instead of putting on the breaks she hit the accelerator which dragged me for quite a distance and in the process crushed my left leg. So, I ended up in an emergency room where they determined that the damage was so severe- They tried to save the leg, but when you sever your femoral artery, you’re bleeding out, there’s not much they can do, but they tried very hard to save it. The truth is even in 1967 in the United States you couldn’t have saved the leg because we didn’t have microvascular surgery and didn’t know how to actually do the kind of work that it needed to save that leg. So yeah, that’s what happened.

Joe: And obviously that’s a very impactful event. And you have this impactful event and you have all of a sudden the realization that flying is going to be off the table at that point and you have this long recovery period of which you have a lot of time to think, so it’s a very open-minded age, it’s a very large event, tell me about the epiphany process.

Iqbal: So, as I was recovering in the early part of my recovery because I was injured so severely, I have vague memories except a lot of pain and the realization that I’ve been amputated because I remember waking up after surgery and realizing the leg was gone. But two, three weeks into the recovery I started thinking about so now what am I going to do. And there was a fascination around what was happening around me; how my care was being delivered. And the first question I had was how does this place run?

[00:06:08]

Joe: Right.

Iqbal: And through that I realized there was a person- They called him the hospital superintendent, but today we call them hospital administrators, hospital presidents, but he was British, and they said, you know, he’s the person who runs this place. And I actually said could I meet that person; I was just curious. And they were very nice, they must have gone and asked him there’s a patient upstairs who is asking to meet you and learn. And so, he invited me, so I was on my crutches and I went into his office and sat down with him, I even remember his name, his last name was McBride. He was very kind, he talked to me about what his job was to run the place. And I took it to heart and said, “This is really interesting.” So, after my discharge I talked to my father and said, “I’d really like to study this thing.” And it was McBride actually that was British who said to me, “I was trained in the national health service in Britain, but America has a different health system and I think that you may want to consider the option.” Because Kenya was a British colony when I was growing up and then it became independent when I was 13 years old. So, we had an orientation to Britain, a lot of my classmates went to England to go to school. But he said to me, “You might want to think about America, it’s an emerging field, it’s a new field in America itself.” In those days. And so, that led me to go down to the American Embassy and engage them in a discussion about it.

Joe: Interesting. So, when you went to meet the superintendent at the hospital, did you feel like that was just more curiosity driven or more driven by wanting to make things better because of what happened to you?

[00:08:00]

Iqbal: Yes.

Joe: You see a lot of people, some of the biggest champions in certain spaces, you know, breast cancer, someone who survived breast cancer, childhood disease, someone who has lost someone to that childhood disease and that gives them the impetus to pursue that as a passion and profession. When you went down this road, how much do you think was that sort of side of it because of what you had been through or just real true general curiosity interest?

Iqbal: That’s an interesting question. I have known about that because others have asked me that. Given that my long career in healthcare they all want to know how did you get into it, especially if you were born and raised in Kenya and what brought you to America. So, the way I think about it – And as you know how the brain works, you know, there’s a little bit of revisionism in that you think you are thinking that.

Joe: Right.

Iqbal: So, I try really hard to actually go back and examine the journey I was on so whenever I get asked what you just asked me I now have been pretty consistent about how I answer that because I have thought about it, which is that clearly the initial part of it was truly curiosity. It was like well, how does this thing work? There’s so many different people doing so many different things, how is my care being delivered? So, there was definitely this sort of curiosity. It is only after I had a conversation with him that curiosity very quickly turned into I think this would be interesting for me to pursue. And the other thing that at the same time I was thinking about was I’m a Kenyan and if I went and got trained in this, I could come back and run one of these hospitals over time after I’ve gotten not only my education, but some experience, I could do this. And this whole idea that as a newly independent country that we have to rely on an expatriate, on somebody else to manage something that is so vital, so essential to the country. And so, it was really a bunch of things that crossed my mind, curiosity, converting to, “Wow, I could do this” to saying, “I should do this because then I can come back and do this,” that’s what led me to it.

[00:10:19]

Joe: But that’s a lot of confidence and vision for a 17-year-old. And that’s what I wonder you said, “Let me talk to the person who runs this place.” And I wonder if the energy is I can make it better. And so, when you were there was the mindset that this is something that is slightly broken that I can make better or this is something that’s working that we can innovate on?

Iqbal: No, I didn’t know enough to make an assessment. [Chuckle] That would be pretty arrogant of me to figure out that it’s not working well. Definitely, it wasn’t something that I said, “Oh, it’s not really working well, I could do better.” I had no idea even how it worked.

Joe: Right, so you were looking up at it at that point, aspiring to it.

Iqbal: I was like whoa, today I use that word, I can assure you I didn’t have that word in my vocabulary in 1967 which is a sense of self-organization. Like how does this place know, given how many people are in various beds, what they need, when they need it, how they need it and how much they need from who? A nurse? Or a technician, or how does it all work? If it’s so intriguing to me. And then again the other word that I use today which is again not something I talk about was the sense of interdependency that not only is it self-organized but there is an interdependency between professionals. That they trust each other of doing the right job at the right time at the right place. That they’re doing something that’s working. And those were taught, but not refined enough for me to say that I understood the sense of self-organization, trust, interdependency all of those things. Only as I begin to study it very quickly I reflected on my thoughts and said, “Whoa, this is what it really is.”

[00:12:07]

Joe: Well, and a lot of those words you described could also be used to describe the military, working together, interdependence, trust, everybody playing their part, how is it all organized. So, coming, given that you started to walk down that path, definitely some parallels there.

Iqbal: You are right. When I was being trained as a pilot I thought about all the people that I relied on, no question. In fact, we were actually explicitly taught about relying on mechanics that checked the aircraft before we got into it. We were relying on the control tower, we were relying on the people who were thinking about the weather who were giving us the reports, we were relying on the flight engineer. In those days, you know, you’d have somebody sitting next to you, it was a flight engineer, or a navigator, and relying on the set of instruments in front of me and realizing that if these don’t work, I’m in trouble. But somebody is obviously maintaining them, checking them, they are testing them, and so yes, that much I learned in my flight training. [Chuckle]

Joe: All right, so then you initially went to school in- what was the program?

Iqbal: In Atlanta, so I went to Georgia State University who gave me the scholarship through USAID. And I enrolled in the business school and took as my major Finance primarily because I grew up in a business family and then I knew that the things that I wanted to study were more at the graduate level. So, I needed a foundation, but besides studying finance which I had already done a lot of sciences, because I went to the British systems, school systems, so it’s what we call all levels and A levels. A levels is like pre-university. So, I’ve done a lot of physics and chemistry and biology and math and I had done all of that. But I wanted to make sure at the university level I took those courses because there was a side of me that said, “Hm, I might pursue medicine. I might go become a doctor.” And so, I was doing both. I was taking a lot of sciences and I was studying finance. So, I was keeping all my options open as an undergrad.

[00:14:10]

Joe: Got it, and before we leave Kenya, what was the family business that you grew up in?

Iqbal: So, we had several businesses. My family is of Indian/Persian origin, but we’ve lived in Africa for over 150 years. So, family was originally from the island of Zanzibar, that’s where my father was born, my grandfather, my great-grandfather, they were all born on the island. So, I was the first one born in Kenya in the capital city of Nairobi which was when I was born it was a tiny town more like railway stop, today it’s a metropolis of seven million people. When I was born there were, I don’t know, 50- 70,000 people. By the time I left in 1968 it has grown to 350,000. As I said, today is seven million. So, and our family, my great-grandfather and grandfather were all traders. So, they were spice merchants and they traded between Asia and Africa. My father then branched off and moved to the capital city and had a couple of small businesses, electronics, he had the RCA franchise. And my uncle had the Coca Cola bottling plant.

Joe: Oh wow.

Iqbal: So, I was exposed to interestingly from the time I was young even though it was a British colony I was exposed to America. I learned very young about Elvis Presley and John Wayne, and all of the American icons. I learned about all of that very young.

Joe: Interesting. All right, so you left university and moved straight into administration?

Iqbal: While I was in school I lost my father the year I was in school. So, you know, I was young, and he was very young he was just 46 when he passed away. And so, my immediate reaction was to go back home, but my mom insisted I had three younger sisters and she insisted that I stayed in America and she said that’s what your father would have wanted, you need to finish school, you can’t come back home and go into the business. And I then took a job initially part-time and then full-time in a nursing home to supplement some income. By the time I was a junior, I was offered a job in a hospital to run the entire business operations. And by the time I became a senior in my undergraduate school they had already given me enough responsibilities in the clinical departments besides the business office.

[00:16:32]

So, I was learning the business fast and through that process I decided instead of going into medicine I would pursue healthcare management. So, I then enrolled in the MBA program while I was still working and got a master’s in healthcare administration at the university. And then spent a year in residency which was a requirement to ultimately get your professional degree, so that’s how I got into the field. And literally the moment I finished my graduate work the company that I was already working in the hospital asked me they said you are ready, you’ve been working, we want to send you to one of our newer hospitals in Biloxi, Mississippi to open it and become its first administrator. So, I was 25 when I went to run the hospital.

Joe: And that leads me back to how does a junior get that amount of responsibility. What was the relationship or how did that job open up to you?

Iqbal: Because the hospital was owned by a medical corporation and the hospital that I was working in in Atlanta which was a Community Hospital.

Joe: But I mean the first position when you were a junior.

Iqbal: Yeah, yeah, when I got the business.

Joe: Because that’s a pretty advanced position for a junior, right?

Iqbal: So, when the hospital was advertising for somebody to come run, it was the new hospital, this is business operations. I applied for the job and I told them that I’d been doing all of this for the past several years at the nursing home, that I understood healthcare, and they brought me in for an interview and there were obviously many other candidates. And the person who was the controller of the hospital and also the vice president, so the was number two, interviewed me initially because I was going to run the business operations which would include, you know, the front office, admissions, and patient billing, and insurance, and account. And I had done many of those courses in school, plus like I said, I grew up in a business family so I had a knack for business.

[00:18:29]

And he interviewed me and then he said, we’ll call you back. And within a few days he called me and said the administrator wants to meet you, I think he went to the administrator and said I’ve got this guy who is foreign born, but he really understands this business and I want to hire him and the administrator said I got to meet this person before you hand him the job. So, he met me and at the end of the interview he said I now I understand why Elliot- who was the controller – wanted to hire you. So, I went to work for them and literally over the two years from my junior to senior year the two years they kept on giving me new responsibilities and I kept on absorbing them. And by the end of my senior year, as I said, I was running clinical departments plus the business office.

Joe: And at that age, how did you manage the relationships with the doctors that they didn’t walk all over you?

Iqbal: [Chuckle] One of the things that if you talk to doctors from my first hospital that I ran all the way to the last hospital that I was the chief executive of, that whole entire journey over 30 years – and even when I was president of the university I still had to deal with doctors. The one thing they would all tell you was that one of the best skills that I had was learning how to understand doctors, how to work with them, how to be deliberate about finding ways to meet their needs, but not at the expense of patients. I always put patients in the middle. And I always figured out that I’m willing to enable, create the enabling environment, the right conditions for doctors to be more successful, to work better, to deliver the quality care, as long as their primary objective was the patient and not the money. And was very tough about that.

[00:20:22]

Joe: Yeah?

Iqbal: It doesn’t mean that I didn’t make good money, but it had to be because the center of what we designed as I thought about care was the patient and the quality of the care.

Joe: And was your style- Did you make it a matter of building the infrastructure to operate that way? Or did you put that out there as sort of this is my leadership style because you almost have to make an infrastructure at that age especially.

Iqbal: I grew up, as I said, very fast. One because I grew up in a business family, two I was the only son, three sisters and a dozen cousins who were all girls. And so, I learned really fast as a young man to be given responsibilities. And then my father passed away and as I said, I realized I was the patriarch of the family. And just as a sidebar I was still a sophomore at that time. And my youngest sister by then was 13 when my dad passed away, she was only 11. And my older sisters were just a year and two years younger than me, by then had gone to Canada to go to school. And my mother called me one day and said I can’t handle your sister, she’s 13, she’s a teenager, it’s tough on me, she needs a dad, so I’m sending her to you. So, my sister came to live with me, that’s when I moved out of the dorms and moved into an apartment, and I basically put her through school while I was also in school and working and I put her through high school in the United States. So, I assumed a lot of responsibility at a young age, and I think between how I grew up and the responsibilities that I took on all lead me to develop certain skillsets about dealing with things and people and issues. And so, assuming responsibility at a young age was something that I just learned.

[00:22:21]

Joe: Right.

Iqbal: So, when I was given these jobs, I think as I said, at the age of 37 I was the youngest president of the university in the history of that university. You know, 150-year-old history I was the first person at the age of 37 to become president at that university taking on a lot of responsibility.

Joe: When you moved on to run the hospital in you said it was-?

Iqbal: Biloxi. The first one, yeah, and then I did several after that.

Joe: And that was all within the same company and you just kept moving to bigger hospitals?

Iqbal: Yes, and then they moved me to New Orleans, and then they moved me to the biggest hospital, which is Las Vegas, so I got to run that hospital. It was at that time that I was called by the Aga Khan Foundation out of Geneva who was building a campus in Karachi, brand new campus to establish that campus at a North American standard. So, they were building an 800-teaching hospital, a medical school, a nursing school as phase one, and since then they have built many more schools. And they wanted somebody who had grown up in a developing country who was educated in the U.S. who would be the bridge because at that time Pakistan was substantially considered underdeveloped to developing.

Joe: Right.

Iqbal: And to think of bringing a standard of care at a much higher level and a standard of education, they needed somebody who actually understood the environment, the culture, and the delta, the gap between what they had and where the aspiration was. And so, I was asked to be the head of the project. So, I went to Karachi for three years to help get that campus off the ground.

[00:24:00]

Joe: What was that decision process like? Obviously, you had been with one company-

Iqbal: Yes, for my whole career. So, I left that and the company was initially surprised because I was so successful at a very young age.

Joe: Right.

Iqbal: And they knew that I would continue growing within the company and assume bigger leadership roles, but they were also very supportive of the fact that there was a calling. There was a calling for me to go back. So, I hadn’t gone back to Kenya, but I was ready to go back to a developing country to deploy the skills and the experiences I had gained to go build something that would benefit that part of the world for a long time to come. So, they actually were very supportive and understood that and said when you return to the U.S. there will always be a home here for you.

Joe: Right. So, you know, there is a uniqueness to how fast you had to grow up. You had a number of facets both from the trauma to your father, to the gender mix in your family that had you sort of skip a few levels of personal evolution, right?

Iqbal: Yes.

Joe: Because you could. And if you take that and look at a normal life’s arch, there’s sort of the coming up years, the learning, the finding your way, and then working towards success, and then kind of redefining your meaning which is when a lot of people start to give back and change their life in that way. Do you feel like when you decided to leave to go to Karachi that it was more that you had accelerated through the professional and you were sort of okay, I’ve been there, done that, and my meanings are changing, or do you feel like I’ve always knew I wanted to go back since I was a child and this is just an exercise of that?

Iqbal: Yeah, it was that. There was still a lot of growing up for me to do, a lot more learning to do, and I sort of knew that, you know? In hindsight at this stage in my life after 45 years in healthcare and I’m almost 70 now, I look back and I thought what were they thinking when they made me the head of a hospital at 25? Even though I was successful, but boy what risk they were taking because I could have really screwed up.

[00:26:06]

Joe: How was your confidence at that when they offered you the job? When they said come to Karachi did you have any confidence lacks or you felt good?

Iqbal: No, I felt very good because I already had a successful career at a young age, I was quite confident that I could do this. But the reason for going was the calling, it was going to be an opportunity even though I was young I thought wow, this is an opportunity to contribute.

Joe: Right.

Iqbal: It wasn’t about giving back, it was more like contributing to potentially something long-term that could have an impact. And now, you know, it’s 30 years later having an enormous impact in that part of the world. And I did that a couple of more times I’ve gone back out of the country. And like I’ve been to Malaysia for five years in my mid 40’s after I left the university I was venture funded and built a whole healthcare company in Malaysia for five years.

Joe: If I were to ask you since you did it, you got the meaning out of it, but if you say you had the calling when you left Karachi, mission accomplished and feeling good? Or?

Iqbal: Feeling very good, came back, I probably came back sooner than I would have come back, I might have stayed longer, but by then the political situation in the country had deteriorated. The Prime Minister at that time was Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. His daughter later on Benazir Bhutto became the Prime Minister. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto the father was Prime Minister and there was a coup by General Zia and he was overthrown. And by that time, I was married and had a child and I was concerned, I was married to a girl from the U.S. who I had met actually in Switzerland when I was there for a meeting. And I decided that I think for a whole host of reasons it was time to come back. And so, I came back and sort of re-entered the U.S. healthcare space and immediately became the chief executive and went to Nashville. By then I went to actually- Didn’t go back to my old company because they had already restructured and had been acquired. So, I went to a Hospital Corporation of America and went to run Hubbard Hospital at Meharry Medical College which was the historically black medical school in the United States which was at that time in distressed, it was financially in trouble and so I went to do a turnaround.

[00:28:21]

Joe: So, you use the term CEO instead of hospital administrator, why?

Iqbal: I think the field had evolved by them and so they were using different titles. They would use executive director of a hospital rather than administrator, then the title evolved to president, then chief executive. Yeah, so it was just an evolution in some ways the healthcare field was becoming such a huge business. And you know, the last enterprise I ran was a six-billion-dollar business. So, it was so huge that when they thought about the people running it and the skills required they thought about paralleling that with corporate America. It’s the same kind of people you would need except a different set of skill sets.

Joe: And what attracted you to a turnaround and how was that process?

Iqbal: So, when I was asked to do that the turnaround was primarily because the institution had lost a lot of federal funding and it was in a depressed part of Nashville, historically black school serving a lot of under-served people under-insured. And I think the company realized that one, I had skills around being very good at the business side of it, but also it needed somebody who would have compassion for what they were going through. And so, they realized somebody who has been overseas, worked in difficult environments, had grown up in another country. And you know, in hindsight I think they picked me because they realized that somebody who would be viewed by that community would just be dominantly would be African American.

[00:30:01]

Joe: Right.

Iqbal: And that I was born in Africa even though I’m not African American and understood what it meant to be a minority in a British colony.

Joe: Right.

Iqbal: And so, they wanted somebody who could do the business side of it, but also have the sensitivity to the culture of what the people were going through.

Joe: How much were you impacted by race when you came to the states and obviously Britain as well? And how did that sort of evolve into how you handled that aspect of the turnaround? Because obviously as the head of that organization you are the main ambassador out to the community which means you’re addressing those issues with the community.

Iqbal: So, your question has two dimensions to it.

Joe: It does.

Iqbal: One was growing up in a British colony where I was in the minority and so are 99% of the people. So, you are in the country, which is being ruled by white British, predominantly black, but some people of Asian/Indian background. So, browns and blacks with traditional apartheid issues of South Africa, which was white controlled. And it was in 1963 when I was 13 that finally Kenya became independent. So, I recall my first 13 years growing up in the country where if you were not white you were not allowed in certain places. You couldn’t go to certain clubs, you couldn’t go to certain restaurants, you couldn’t go to public facilities, you weren’t allowed. There were swimming pools which were for whites only, you know? I was fortunate enough to be able to go to a swimming pool in my school which was multiracial so it didn’t matter, but millions of other people were not able to. And so, I grew up seeing that as you can imagine how it would make one feel when you go through something like that and then after independence obviously things changed. And then I come to the U.S. and I go to the South and I remember growing up in Kenya admiring John Kennedy and Martin Luther King and then obviously the assassinations of somebody who I admired and I’m a young man and then subsequently the assassination of Martin Luther King.

[00:32:17]

And also, I was exposed to the Peace Corps which came from America to all these countries and so I met a lot of Peace Corps workers. And I thought wow, these people are good people, they don’t treat you as inferior. And then when I come to America and I’m in Atlanta, Georgia the home of Martin Luther and I realize the racial divide. And I see it in school, I see it in housing, I saw it everywhere. Now I was not black, I was not white, interestingly I was a novelty because people were quite intrigued to see somebody was born in Africa of Asian background with a British accent, this is what I had 45 years ago, and they were intrigued by that. So, in some ways it was sort of weird, I was like a novelty for a while. But I absolutely experienced the racial tension growing up. And then the one thing that I quickly learned, which I also learned in Africa, that people can take a lot away from you, but they can’t take away your brain. If you are good at something at some point you will be recognized. And so, I excelled at school, I excelled at my work, and very soon I realized that people who engage with me saw beyond my color, they just saw me, not my color. And on top of that, as I said earlier I was quite self-confident as a young age. So, I never thought about it, but I have experienced over, explicit, racial discrimination as a young man in this country. I experienced it in Alabama, I experienced it as a young man in restaurants, in shopping centers. You know, when I was in my early twenties, I experienced all of that.

[00:34:02]

Joe: But when you took over the job in Nashville-

Iqbal: Yes.

Joe: Now it becomes-

Iqbal: More profound.

Joe: – more than you because now you have to –

Iqbal: Yes, because the school was historically black. And so, part of my task that I gave myself was to actually, as I said, walk in the shoes of the fisherman. Understand where they were coming from rather than them understanding who I was. And just because I grew up in Africa doesn’t mean I automatically knew and understood the African American cultural, I just didn’t. And so, immersed in that. And you know, I learned about the history, the challenged they experienced, the discrimination, the disproportionate funding. And when funding came how the City of Nashville conveniently spent more of their resources on the other side of the tracks than this side of the tracks whether it was in housing, in healthcare, in any public service, you could just see it the roads were better on one side of the other one. Street lighting was better here than there. And so, it was obvious to me, and this was not just Nashville, it was in every city in America, especially in the South this happened. So, I really made it my objective to understand, learn, engage, immerse. And so, I met local African American leaders, I went to their churches, I participated in social events, even though my wife was white, and my children were bi-racial, I made it a special effort to do all of that. And through that I think there was a sense of acceptance of who I was. They saw through me, not my color, but my commitment of what I was trying to do.

Joe: Then you’ve gotten to a good resting place there with the students and the board and that sort of community.

Iqbal: Yes.

Joe: But you still are a high-functioning sort of outsider with a unique in-roads into it and then you have to take that confidence, and acumen, and now new understanding of what the plight is of that, and then represent that back to the people with the money, so how do you handle that?

[00:36:11]

Iqbal: So, you went to the heart of what I had to do which is President Reagan had just come into office and the secretary of HHS was Schweiker from Pennsylvania. And we were notified, we meaning the institution, that they were going to cut off what they call distress funding. And we were in default of the tax exempt bonds that have been floated to build the hospital and the other funding came to the Medical School, the Meharry Medical College and they were going to cut it off. And I went down to Washington and met with the staff of HHS and basically said to them, at least this is what I was told, President Regan had decided we’re going to stop this distress funding, we’re not going to give them any more money. So, I basically said to them, to the staff, does the president and the secretary have the context of supposedly this decision to shut off the funding. This is a historically black medical school, it’s been around a hundred and some years, that 50% of the black doctors and dentist practicing in the United States primarily in underserved areas, right? They’re not practicing on 5th Avenue New York, they’re practicing in poor communities came from this school this one, Howard in Washington, obviously there was the Tuskegee in Alabama but that wasn’t a medical school. But these are the schools that have created the human capital to serve the citizens of this country who happen to be black and they’re going to shut off the funding. So, not only are you shutting off the human capital they’re providing, but the historical value of this and what it means in our own history and the backlash that might come from all of that. I mean, has anybody thought through all of this?

[00:38:10]

Joe: Not to mention that when the doctors leave those distressed areas that’s only going to make the burden on the government-

Iqbal: And let’s just be honest, a lot of those poor areas of American primarily which were African American, at that time there wasn’t a very big Hispanic population in the Americas.

Joe: Right.

Iqbal: It’s grown in the last, you know, 40 years or so, but it wasn’t that big, if it was it was concentrated in a few areas in the country, Texas, and Arizona, and New Mexico, but now it’s all over. You didn’t see any white doctors practicing in those areas. And I’m not knocking them, it’s because they were serving in other areas, but there was a real need for people from the community being trained to go back and work in the community. And so, I basically said to them you’ve got to put me in front of the right people so that they don’t make what I call a stupid decision. So, I’m not coming here to beg for money, I’m telling you you’re going to create a human capital problem and you’re going to create a serious backlash from a lot of groups all over the country because you’re shutting down the historical school. And whatever process they went through internally we got notified that the decision had been pulled back, so we continued to get funding.

Joe: That’s great. Then how long did you stay in that role?

Iqbal: I was there just under two years because it was a primary turnaround kind of job and then the idea was to recruit potentially if we could find— Which we did— An African American executive to succeed me because I thought it was the right thing that the community be served by one of its own, which we did find an outstanding person to come into that role. And then I moved on and moved to Miami for a few years to run a health system there and from there went to California for a short time to launch the international division of the healthcare company, we were going to work in the Pacific. So, I was living out of there and working in the Pacific. And it was during that time that I was recruited to come to Philadelphia to become the chief executive of the healthcare system for the university and then two years later I became the president of the university. And that was a big transition for me because I left running healthcare and systems into academics and going to higher education. And I was honored that I was recruited and it was a big step in my life to move into that career and I did that for seven years.

Joe: In which university?

Iqbal: Hahnemann University in Philadelphia. And then I decided at that point to step out of academic life- Actually I took a sabbatical, which is not uncommon after seven years, and I studied healthcare systems in Eastern Europe which were emerging from communities after the collapse of the Soviet Union in Southeast Asia which was referred to in those days as Tiger States Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand. So, I went to study the healthcare systems for six months and during that time I decided that this was an opportunity for me to be an entrepreneur in the academic life and take all my years of experiences and launch a healthcare company. And I selected the market to be Southeast Asia over Eastern Europe and went to Warburg Pincus large equity fund in New York and raised capital with them, launched a company and spent five years building the healthcare company in Asia, which I ultimately sold.

Joe: So, the raising capital piece of that, was that a connection that you had? Or did you go to multiple places and end up there? Or what was that pitch process like?

[00:42:01]

Iqbal: No, the connection was that during my sabbatical in Asia the head of Warburg Pincus in Asia was based in Hong Kong. And I met him at a meeting in India. He was there assessing a project in India to invest in and I happened to be at that time in India asked by Apollo Hospital, the company that he was looking at, the president of that company to give him some advice. So, I was on the other side assessing the opportunity. His name was Chip Kaye who is now president of Warburg, but at that time he was head of Asia. He met me and we struck up a conversation and he said to me, “If you want to launch a company in Asia, why don’t we fund you?”

Joe: That’s easy. [Chuckle]

Iqbal: He said to me why don’t you come to New York? I’m coming to New York and meet the president of the health group; his name was Rod Moorhead. He said come meet him and let’s have a conversation. And one thing lead to another and we came to an agreement that I would go launch a company in Asia and base it in Kuala Lumpur and they funded me.

Joe: And what was the last-

Iqbal: For the company, I built up the companies, it started as aggregating primary care initially and at the same time using the leverage of the primary care aggregation to establish ambulatory centers, surgical centers, and then build two hospitals which would be the feeder from our primary care network. But the key thing was to bring systems and processes that would create efficiency and effectiveness, and high-quality of the delivery of care and at the same time accessing the intellectual capital, the kind of training and education that was available to upgrade the staff and then take them back. So, on both the business side and healthcare delivery side we participated in training business staff, and then we’d train doctors, we’d train nurses who have been trained in the country and then we give them additional training at a higher standard to come back that created the sort of privately financed to serve the emerging middle class the kind of care that they were seeking. So, that’s what I did. And we built that company and I left and the company continued and I sold my interest in the company. And that company ultimately three, four years after I had left went public, it’s called Qualitas it’s trading on KL Stock exchange, very successful.

[00:44:30]

Joe: And is it at this point that you started the consulting business.

Iqbal: So, no, then I came back to the U.S. and was doing some consulting on my own at that time, but really testing what I wanted to do next because I knew I was being approached by headhunters to go become president/CEO of the healthcare systems. And I thought, you know, I’m not sure I want to get back into doing that, but while I’m thinking through it, and by this time my kids were growing up and a couple of them had gone off to college and I was just thinking and I had re-married and my wife who was originally from Florida, that’s why I’m here now, she brought me back to St. Pete. But we met in Philadelphia and she was a banker and then became a venture capitalist, in fact she was a founder of Venture Fund in Philly. But I started thinking about what to do next and got a call- And I was advising a few bio-tech firms on the West Coast who were also Venture funded. So, the venture company came to me and said, “Could you sort of be the chair of a couple of companies?” They had entrepreneur chief executives but we want some senior leadership in those companies. So, one was in San Francisco, one was in San Diego. And I was commuting running those companies and I got a call from the founder of eBay, Pierre Omidyar, who then recruited me to be the first president of his foundation after he had taken eBay public and created a substantial amount of wealth for himself. And he established the Omidyar Foundation, which ultimately morphed, while I was there, into a multi-sector network organization because it does philanthropy, venture investing, deploys private capital for social good, and some public policy work.

[00:46:16]

So, we do all three things. So, I became his first president in 2002 and stayed there till 2007 to scale it. And so, I ran that foundation for five years and when I retired from that it was then that my wife Janet said, you know, she wanted to come back to St. Pete. She had left here when she was 18 so she had been gone 35 some years. But she wanted to come back, her mother was aging and so she said I want to come back and spend some time here. So, we decided to come back not with the idea of we were going to live here long-term, just to come back and spend a few years. It’s sort of an initial landing pad. And just over time, you know, the city morphed and changed and grew. We fell in love with the city, we loved the people we had met. And here we are 10 years later made St. Pete home. And so, now it’s more than 10, 11, we came in ’08. And so, over those 11 years after I was here it’s when I established my boutique practice and my first client was John Hopkins and then Atlantic Health, then Emory University, and Emory Health, and now the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

Joe: One relevant to St. Pete, obviously John Hopkins ended up with a second true John Hopkins location here.

Iqbal: Yes.

Joe: What role did you play in that?

Iqbal: So, I was involved in the initial assessment of that opportunity on behalf of Hopkins. So, I was on the Hopkins side. Then when the decision was made, working with the board of All Children’s to bring them into John Hopkins. I recruited some of the staff from Hopkins and was involved in the first two years of what we call integration. So, now Hopkins has been here for seven, eight years, but the first two years I was involved in helping integrate what I would call the sort of capacity of Hopkins. You know, it’s intellectual, human, social capital, all the things that were there into All Children’s and the consolidation of the back office and all. So, I spent two years doing that as a consultant helping them, so that was the role that I played in that. And then stayed in role for another year sort of quarterly meetings and strategy and advising in those days. Yeah, so it was 2013/14/15 those two or three years.

[00:48:39]

Joe: You know, you’ve had a very large variety, almost three lifetimes worth in what you’ve done.

Iqbal: And I haven’t talked about my life in Africa. I’m very involved because I was appointed by President Obama to the African Development Foundation which is a U.S. government agency back in 2013 I was appointed. So, I’ve been on it now going on six years on the foundation where I’m a board member but I’m also very active. I’ve led the strategic planning committee, I was the chair of the search committee that brought the new president there and I’m in Africa three to four times a year for two weeks at a time working in conflict/post-conflict Africa in 18 different countries doing economic development, social development, working with local communities, empowering women, empowering youth. So, I’ve been involved in the power of Africa project to bring off grid energy to rural Africa and the YALI Project which is training young Africans to become leaders. So, I spent a good bit of my time now as a volunteer working on the continent.

Joe: I would like to get a little of your wisdom. And with all of that experience and all those inputs you’ve had all this time, I want to talk first of all about wealth disparity. So, obviously you’ve seen it from many different angles. So, someone mentioned recently that wealth disparity has always been there, that it was always the king, or the monarchs, or the leaders that had it, but we’re certainly digging into more intellectually now with as we can see the flow of capital more transparently. What are your thoughts on wealth disparity and its role?

[00:50:11]

Iqbal: So, I’m very troubled by that. I don’t give myself a label, you know, about being a liberal, or a socialist, or conservative, or I don’t label myself. I label myself as a humanist, I consider myself a world citizen, literally. I’m U.S. citizen, but I’m a world citizen. I’ve lived in parts of the world, I’m a traveler. And I’ve not only seen it, but I’m troubled by it more and more. And I see the kind of distortion it creates in human life, in access to services, and that wealth disparity especially when you look at the bottom half or two thirds or three quarter of America which is where the disparity is becoming bigger and bigger, the stresses it causes on families, the lack of opportunities therefore that they have. Forcing young men and women to not pursue their dreams and education because they have no choice but to make a lively hood just to survive. So, you know, from my perspective the wealth disparity is increasing contributing to breaking down the long-term value proposition of what America stood for and what it’s social and human values were, not just here, but all over the world. And I’m seeing that being eroded. I’m also troubled by the fact that so many of our policies that I would think that our elected officials who are supposed to represent by the people for the people actually represent very small number of people, most of the other people seem to be marginalizing the process. And what does surprise me, yes it troubles me, but surprises me, is how many people continue to vote against their own self-interest. That they’re not thinking about the people who they are electing who are not serving them except during election time to get their votes. All of that is troubling.

[00:52:13]

Joe: What’s your best explanation for why they do that?

Iqbal: Well, there are probably many things one could think about, right? Which is all of this comes from being enamored with charismatic people and therefore you believe in something or they think that they will do something for you until you realize that you have to do it for yourself, nobody is going to do anything for you. I think the other explanation is that we have lost the kind of transparency, information gets distorted easily, you know, talk about what has happened to the field of journalism and news. I’m troubled by the fact that there are many ideological movements emerging in the country, maybe they’ve always been here, but I thought at least in my time in this country I thought so much of that was finally achieving a level of playing field. People were thinking about the difference, but instead I’m seeing ideology re-emerging and I think people are latching onto that ideology. And sometimes people are latching onto single causes. So, they vote against their self-interest because there is one cause that they are committed to and they will follow that at the expense of the many other things that they are actually losing out on. So, there are many, many of those sort of issues. You and I could have hours of discussion on all of that, but why people do that and what is happening. And I’m yes, very troubled by that, you know, this country gave me amazing opportunities. I achieved my success in this country, I worked hard for it, but I achieved it here and he told me that at some point no matter who you were or what your background was, what your color was, what your faith was, you could achieve. You know, people used to talk about this is the land of opportunity and I’m seeing so much of that getting eroded, it’s very troubling. I’m saddened by it. But I’m fighting it in my own way.

[00:54:12]

Joe: Yes.

Iqbal: Fighting it meaning I’m working hard to level the playing field. I work hard in things that would give people who lack opportunity access to opportunity to create the enabling conditions and environment for people. I do it in Africa, I’m doing it here too in my own ways. I don’t want to leave this conversation without saying that even though a lot of my work is taking me out of the country and out of the region here, but for the past few years my wife was very active in the community. She has served on many different boards more recently the Chair of the Florida Orchestra has been asking me to give more time in the community. So, I became involved in the World Affairs, I’ve been involved working with the OPEN Initiative, I’ve been meeting with the university officials at USF St. Pete to think about how the community and university could work together. So, I am starting to devote more time back into the community here besides nationally and internationally. And I hope to continue doing that.

Joe: That’s wonderful. Just a rough guess, lifetime air miles, how many you got?

Iqbal: How many air miles have I flown?

Joe: Millions.

Iqbal: Oh wow, yes. I mean, when I had the company in Asia just during that four-year period I flew back and forth to Asia about 47 times just during that four-year window and other flights in between. Yeah, I mean on the average I’m on a flight pretty much every week and four or five times a month I’m on a plane somewhere in the U.S. or in the world.

Joe: So, we end every show with a shout out, someone that you think is doing good work that doesn’t get as much attention that can be an organization, that could be anything you want essentially that you just want to shine a little light on.

[00:56:00]

Iqbal: So, I think I could shout out many organizations internationally are doing amazing work which I’m really proud of and who I’ve worked with or supported. But I think given that I’m here in St. Pete sitting with you here I think it’s fair to give a shout out to some local organizations who I think are doing amazing work. Not because my wife is the chair, but I’ve become more informed about the work of the orchestra. To be honest when I first got to know the orchestra and my wife was getting involved I told her, you know, this bunch of elite people going to the orchestra, predominantly white, and you’ve been involved in many social things. She was on the Foundation; she still is on the board of the Foundation for Healthy St. Pete. She was on the board of the Free Clinic. I said this is interesting you want to do this. She said I’m doing it because I want to enhance the connection of the orchestra to the community and through my engagement with it I have learned the thousands and tens and hundreds of thousands of people who get exposed to an opportunity through the orchestra, the kids who learn music, concerts they’re doing. Now I’ve learned they do a lot of community work, so I want to give a shout out to them. I want to give a shout out to the Free Clinic; I think they do fabulous work. I am starting to be more involved in U.S. St. Pete in any way I can. I think highly of the Chancellor Marty Tadlock. And I think that institution has done a lot for this community and I think can do more and I look forward to working with them. And then there are small emerging organizations, like yours, your organization and the OPEN Initiative. They are still young and they are looking to have an impact in the community. And I hope to be able to work with them also in whatever I can do to contribute to that. So, while you’re asking me to give a shout out I’d say you and your team are doing an amazing job contributing back to the community even though you are a business, I know how much work you do pro-bono and how you support the community. So, thank you for that.

Joe: I appreciate that, thanks. Well, that’s a perfect note to end on as far as I’m concerned. [Chuckle]

Iqbal: Wonderful, thanks for having me.

Joe: Thanks for coming in.

Iqbal: Appreciate it.

0 Reviews on this article

About the host

Joe Hamilton is publisher of the St. Pete Catalyst, co-founder of The St. Petersburg Group, a partner at SeedFunders, fund director at the Catalyst Fund and host of St. Pete X.