Episode 060

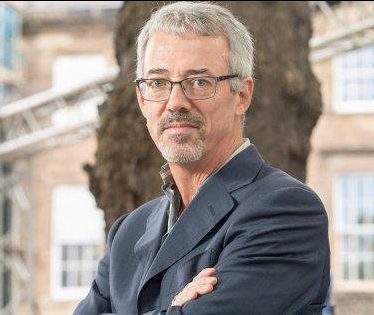

David Mearns, Shipwreck Hunter

Shipwreck Hunter: David Mearns talks process, finding the unfindable and stories of his most memorable discoveries

On this episode of SPx, Shipwreck Hunter and Aresty speaker David Mearns joins Joe in the studio to talk about uncovering some of the world's most famous shipwrecks and finding the "unfindable." Mearns shares the painstaking process of locating a shipwreck, the all-or-nothing stakes and the controversies attached to these discoveries. He shares the incredible story of the HMAS Sydney and the Kormoran, and how he cracked the code to find the location of the ships' wreckage in 2008.

Key Insights

- On this episode, David Mearns joins Joe Hamilton in the studio following his lecture in the OPEN Aresty Speaker Series. Mearns is a world-famous shipwreck hunter.

- Mearns attended the University of South Florida College of Marine Science, where he studied geology and oceanography, two subjects he still uses in his work today.

- Bob Ballard, who discovered the Titanic, had said that the Derbyshire and the Sydney could not be found. This hampered the campaigns of many family members to find the famous shipwrecks. Mearns eventually found both ships.

- On Bob Ballard: "I wouldn't say bested him, but I went out and found things that he said wouldn't be found ... It just puts a little bit more pressure on you to overcome that resistance from somebody as famous as he is."

- On process: "I have a starting point. And then beyond the starting point you have a big zone of uncertainty where it could be located because the navigation isn't perfect. So, what I focus on is those navigational clues, position, latitude, longitude, range and barring, eye witness statements, observations about currents, observations about winds."

- Mearns says a project must also be fundable, which requires a great deal of research on the front end. Mearns will put a pitch together and approach governments, television companies or sponsors like Paul Allen, who sponsored many of Mearns' discoveries.

- "Then you start putting together the actual expedition, decide on what type of ship you need, what type of instruments you need, you put together your crew ... So, you're talking four to six months for planning a major expedition which could last anywhere from a couple of weeks to 45-days or so."

- Most of Mearns wrecks are found with a side scan sonar, which utilizes a low-frequency, wide-swath sonar.

- On sonar: "These soundwaves - they race across the ocean floor and anything that is sticking up or hard it reflects that sound back to a receiver and that's recorded on computers top side. And I learned that trade at College of Marine Sciences as a geologist characterizing the seabed - whether it's rocky, whether it's sediment. And I decided to learn it for finding shipwrecks."

- "These low-frequency 33, 36 KHz, they can cover five kilometers in a single pass, three nautical miles. So, we're hoovering up great big swaths of the seabed searching for objects with the detection capability for picking up relatively small shipwrecks."

- In the very deep ocean, known as the abyssal plains, the ocean floor is fairly homogenous, but in somewhere like the English Channel, there can be thousands of shipwrecks to discern.

- Mearns rarely recovers objects from the shipwrecks he finds, as most of them are war-time wrecks and therefore mass gravesites.

- The exception to that rule was the recovery of the H.M.S Hood bell, which was recovered in 2015, 14 years after Mearns first discovered the wreck.

- In a highly secretive industry, Mearns has coined the phrase, "Democratize the seabed." He wants the public to see what he and very few others have been able to see through their work. But treasure hunters pose a threat.

- "Ideally you want to make everything open and free, and democratic, because these are shared underwater cultural heritage, not just of one country, but of the world's. But how do you do that in a responsible way to make sure in the first instance that cultural heritage is protected from people doing the wrong things with it?"

- Mearns tells the story of the Kormoran and the Sydney, and the battle that took place between them in 1941. He shares how he cracked the code to eventually find the Sydney and the Kormoran in 2008.

- On Paul Allen: " Paul was a remarkable man. And his legacy will live on forevermore and not just in the area of shipwreck exploration, but the Allen Brain Institute, his work in conducting census of wild African elephants. You know, he had a huge role in solving the problem of Ebola two years ago."

"In the deep ocean what we call the abyssal plains, you know, deeper than 4,000 meters in the middle of the ocean, you know, generally unless there is lots of geology there it's flat and homogenous, and you don't see anything else, and there's no other shipwrecks. But if you work in an area like the English Channel for example it's full of wrecks from the wars, World War I, World War II. Thousands of shipwrecks have been sunk around the English isles."

"There's no 50% success, 80%, it's only successful if you find it. And your reputation is based on your track record of finding it. And I've always approach a project like I'm going to be judged on my last one."

Table of Contents

(00:00 to 01:48) Introduction

(01:48 to 04:28) David’s Speech At The Mahaffey

(04:28 to 08:20 ) The Overall Process of Shipwreck Hunting

(08:20 to 10:55) Locating A Shipwreck

(10:55 to 11:59) Recovering Items From Shipwrecks

(11:59 to 16:02) Secrecy In The Trade

(16:02 to 24:01 ) The Story Of The Kormoran And Sydney

(24:01 to 27:42) The Detective Work Behind The Kormoran Account

(27:42 to 33:00) Stakeholders Behind The Expeditions

(33:00 to 36:36 ) Different Sectors In Shipwreck Hunting Community

(36:36 to 39:51 ) The Legacy Of Paul Allen

(39:51 to 40:56 ) Conclusion

Full transcription:

Joe: Joining me on SPx today is David Mearns who is with Blue Water Recovery.

David: That’s correct.

Joe: Welcome sir.

David: Well done, thank you.

Joe: So, you were an Aresty speaker, we were just talking a little bit about ping pong. And I think before we go anywhere we should say that you not only beat, but can we say wiped the floor with Jim [Aresty]?

David: You want to put this on the record? Our ping pong?

Joe: I do, only because he beat me last time we played and so this is my chance to get what revenge I can. If I can’t get on the table I will get for posterity on a podcast.

David: Okay, well Jim you asked for it, so here it comes on the record.

Joe: Yes, and you notice he has the whole apparatus with robot player and everything like that in there.

David: Yeah.

Joe: So, there’s really no excuse for him to lose ever, as far as I’m concerned.

David: Yeah, I was kind of playing left-handed, but yeah.

Joe: Oh, nice. So, we’ll dive into just the fun topics since Jim and I have a ping pong rivalry. We’ll preface by saying you gave a great talk at the Mahaffey as an Aresty speaker a couple of nights ago. And that was put on through OPEN and USF. And really a lot of people came together to fill the house and you did a great job.

David: Thank you.

Joe: So, I have a ton of follow-up questions from that, but obviously for folks who weren’t there will want to dig into some of the setup of it. But the first thing that jumped out at me I remember is a couple of times you made sure to mention to the audience that you bested Mister Ballard.

[00:02:09]

David: Well, I wouldn’t say bested him, but I went out and found things that he said wouldn’t be found.

Joe: Which seemed to make it a lot sweeter when you found them.

David: Well, it adds to the story, doesn’t it? Because for people who don’t know Bob Ballard is the guy who lead the discovery of the Titanic. Which in my book is still the most famous shipwreck of all time, which makes Bob Ballard the most famous shipwreck hunter. And you know, I’m a little bit younger than Bob. But it was important to those two groups because they fought and campaigned for many years for these ships to be found. One is the Derbyshire, a large loss of life, the other one is the Sydney, and equally large, greater loss of life. And when Ballard was asked he said they couldn’t be found, it set back their campaigns because he had this great fame and notoriety as a shipwreck hunter. So, I think it was important to them that they were able to break through that resistance and finally find somebody who was willing to take it on and for governments to fund it. So, that’s the reason why we make a point of mentioning that. Nothing against Bob, he’s a great guy, and I know him, and we get on fine.

Joe: I think a few of our listeners minds may be blown right now that James Cameron didn’t discover the Titanic, but it was actually Bob.

David: No, but Jim will tell you that he’s done on Titanic as much as anybody. I think the only people who dove more are the Russian pilots who piloted the submarines. But the movie was almost a byproduct of his interest in the Titanic.

Joe: How does that work in the space if someone like Ballard does come out and say it’s difficult? And because of him being the leading voice, you know, funding probably gets more difficult for the efforts. And then people who are interested in finding that, you know, the families and the governments then does that sort of cause an awkward-?

David: It’s another hurdle that you’ve got to get over. And it just makes you do your job even more carefully and thoroughly to any concerns that he had and he had valid concerns. So, I have to make sure I overcome those concerns with my research and my planning for how to find those wrecks.

David: And fortunately, with the Derbyshire and Sydney we successfully located both of them. It just puts a little bit more pressure on you to overcome that resistance from somebody as famous as he is.

[00:04:20]

Joe: So, with that then before we get into the Sydney which I thought was super interesting especially leading up to the book and the code which I’ll tease now I’ll get into later. But can you talk a little bit about how it works? So, from a technology standpoint it certainly seemed like technology has advanced rapidly, you are able to cover so much area. But what is the general process when you hunt for a shipwreck?

David: Well, the starting point is research and archive. First you need to know the shipwreck, the name of the shipwreck, when it sank, why it sank. And with that little information you can start going into archives. National archives, these are depositories of public information. A lot of it created during the war if you are looking for World War II shipwrecks that have now been declassified. A lot of the information I’m looking at originally was classified. It has been declassified after a 30-year period or a 50-year period. And you’re searching for clues, navigational clues, that will give you a starting point to the search. The first question a lot of people ask you about shipwreck hunting or if you’re looking at a specific wreck, do you know where it is?

Well, of course I don’t know where it is because it wouldn’t be a search, but I have a starting point. And then beyond the starting point you have a big zone of uncertainty where it could be located because the navigation isn’t perfect. So, what I focus on is those navigational clues, position, latitude, longitude, range and barring, eye witness statements, observations about currents, observations about winds. And that’s where my oceanographic background comes in. I didn’t practice as a physical oceanographer, but I was taught the basics of it here at the College of Marine Science then a department. And that allows me to assess this information as a sort of holistic group of disparate clues that leads you to a starting point we call the most probable sinking position and then the zone around which you have to be prepared to search before you find it.

[00:06:09]

Joe: So, even that process can take a long time and consume a lot of resources. So, at that point have you engaged with interested parties who are funding that? Or how do you decide which of these to dig into?

David: Most often I start the process myself before I start looking for funding. By the time I come to looking for funding I know that wreck is findable. And not just findable that I have a high degree of confidence in finding it. These deep-water projects, search projects, in 3,000, 4,000, 5,000 meters of water, they cost millions, you know? Not tens of millions, but three, four, five, six million dollars. And you generally get one shot and it’s either a success or failure. There’s no 50% success, 80%, it’s only successful if you find it. And your reputation is based on your track record of finding it. And I’ve always approach a project like I’m going to be judged on my last one.

You’re only as good as your last project. So, you really have to make sure, first off, it’s findable, that you have a high degree of confidence that if you’re initiating the project, that there’s a rationale or a reason for finding it. That it’s fundable, there is significant interest there to whoever the potential sponsor is that they say, “Yeah, I believe in your vision to locate it for whatever reasons.” And so, all of that research and planning has to be done in advance. And generally, I do that myself on a specular basis; I have the time to be able to do that. And then I finally start putting pitches together, and whether I’m approaching governments, or television companies, or sponsors like Paul Allen, who sponsored quite a bit of my work.

Joe: So, let’s just say then you have an idea, you research it, you feel good about it, you find stakeholders, they fund it, what happens from that point on?

David: Then you start putting together the actual expedition, decide on what type of ship you need, what type of instruments you need, you put together your crew. Generally, these things are all around the world so there’s a lot of shipping and time. So, you’re talking four to six months for planning a major expedition which could last anywhere from a couple of weeks to 45-days or so. Then you go out and you execute your plan and hopefully you’ll find what you’re looking for.

[00:08:16]

Joe: What’s the technology involved in the process involved in executing? I was shocked when you said some of them once you got on it with the technology that you have you’re talking 30, 40 hours of search time. How does the actual physical search work?

David: So, most of the wrecks that I have found I’ve located using a special type of side scan sonar, a low-frequency, wide-swath sonar. The side scan sonar is a tone acoustic device that puts sound into the oceans and it gives you a map plan of the seabed and objects sticking off of the seabed. These soundwaves they race across the ocean floor and anything that is sticking up or hard it reflects that sound back to a receiver and that’s recorded on computers top side. And I learned that trade at College of Marine Sciences as a geologist characterizing the seabed whether it’s rocky, whether it’s sediments. And I decided to learn it for finding shipwrecks.

And the type that I use, these low-frequency 33, 36 KHz, they can cover five kilometers in a single pass, three nautical miles. So, we’re hoovering up great big swaths of the seabed searching for objects with the detection capability for picking up relatively small shipwrecks. And that gave us a huge advantage of how it was being done before because we can find things a lot faster. So, this is where, you know, finding the H.M.S. Hood within 39-hours, the Kormoran in 64-hours. It’s not measured in days; it’s measured in hours. Now that’s not always the case. You have to be looking in the right place at the right time, but still, you know, it does show how effective this low-frequency sonar can be used if you apply it in the right way.

Joe: I’ve seen these programs, or whatever, where these treasure hunting companies are just combing the ocean looking for these things; there’s one based out of Tampa here. And when you’re doing this, are you seeing multiple hits and then it becomes an identification exercise?

[00:10:08]

David: No, it’s exactly that. You have multiple hits. And it depends on where you’re searching. In the deep ocean what we call the abyssal plains, you know, deeper than 4,000 meters in the middle of the ocean, you know, generally unless there is lots of geology there it’s flat and homogenous, and you don’t see anything else, and there’s no other shipwrecks. But if you work in an area like the English Channel for example it’s full of wrecks from the wars, World War I, World War II. Thousands of shipwrecks have been sunk around the English isles. So, it’s what we call a target rich environment. And the targets can be either geology, which often times can be confusing and make it difficult to find it, or other shipwrecks similar size, similar era, of the one you’re looking for. Then as you say it becomes an identification problem.

Joe: And how often are you, you know, of the wrecks that you find, how often are you recovering things from it?

David: Infrequently. Any of the wartime wrecks, anything that was a warship, especially if loss of life is involved, then we don’t touch them. It’s look but don’t touch. There are the exceptions, rare, extremely rare, like the bell of HMS Hood. So, the Hood is a massive war grave. 1,415 men died, it’s the largest loss in British naval history. But when I found that in 2001 we also saw the bell lying in a debris field. And it took many years before we all got comfortable, including the soul living survivor at the time Ted Briggs, with the idea of actually recovering that bell because it was at risk from somebody else coming along without the right intentions of recovering it, selling it, or doing something stupid. And we recovered it on behalf of the Navy and gifted it to the National Museum of the Royal Navy in Port Smith where it is displayed permeating. And that was a project sponsored by Paul Allen. So, that was on that I came to him with.

Joe: Interesting. So, obviously there are a lot of wealthy people in the world who would have the means to rent the equipment to get to some of these wrecks for their own sort of personal collections. How much does that come into play as far as when you find it? Do you try to keep it a secret? I know you had mentioned Ballard had kept one of them that you looked for a secret from you and you had to actually re-find it which means that is now two people that have found it. So, how much does that come into play the antiquities trade?

[00:12:15]

David: Generally, the industry is very secretive for a number of reasons for a number of reasons. One because people just don’t want anyone else knowing what they’re doing. They are maybe doing things unethically and they don’t want people to know about it. Or they are salvaging things whether legally or illegally that has great value, so they want to make sure that no one else goes there. The one thing about the oceans particularly beyond the territorial seas and beyond the EEZ there’s no jurisdiction that covers it in a way. So, it’s almost a free for all. And so, you could find something that you have spent a lot of money finding it and you think you have the rights to it in terms of either the property rights, or the image rights, or anything else. But if somebody else comes along and re-finds it, well, you know, they can promote something or release images and there’s nothing that you can do about it. And there’s actually been a test case on that on the Titanic where somebody wanted to bar another team taking photographs of the Titanic.

And I believe that case went actually to the Supreme Court where they ruled if somebody wants to take a picture of the Empire State Building, you can’t stop somebody else from taking a better picture of the Empire State Building. And it’s the same thing with something like the Titanic in deep water. So, it’s a part of the industry and it’s one that actually hinders us. It’s not good for the public. And more and more I feel that we need to unlock these secrets. I’ve coined a phrase democratize the seabed. And I think there’s ways that we can actually do that. And for the treasure hunters that’s not great, but it cuts both ways because if you democratize the seabed so that anybody can see it just like go on Google Earth and the shipwreck is there, you can look at photographs of it, some of these things we want to protect, you know? And once you release that position, they’re no longer protected. And that is a real issue of people salvaging war ships, people doing things illegally, unethically, or doing it in the wrong way. So, it’s a complicated question.

[00:14:07]

Joe: Well, first, it strikes me I remember during your talk you said that on a couple of occasions when you found the Japanese ship that Paul Allen had tweeted it and you were getting back translations of the instructions for the catapult or something that was found, right? And then the same thing that the Australian Prime Minister went on TV live the same day you found, or within a couple of hours, of finding the Kormoran. And people are going to see these big ships out here and they’re going to know where you are. It’s not going to be a secret.

David: Yeah, and today there’s an automated system that tracks ships. So, the public can watch vessels going out and searching for things. So, 20 years ago that technology wasn’t around. It wasn’t even around 10 years ago, now it’s commonplace. And you’ll see on the internet, Twitter, I was searching for Emiliano Salas’ plane, people knew when I was leaving port and what was going on. You know, to the point they’d know what track lines you’re running. So, you can’t hide these things the way you could hide them before. But, you know, for example in Sydney afterwards I wrote a book about it. And there was also the conspiracy theory saying we wanted to make sure that we put those to bed. That people knew exactly where the ship was.

One the cover, the front cover of my book we gave the position of the Sydney. That’s because in Australia they have a legal system to protect the wreck. They have a real motivation to make sure that people don’t go out and disturb the shipwrecks. So, there’s a regime in place that even if we reveal the precise position, that Australia will do their best to make sure nobody goes out and messes around with it, unauthorized disturbance. It helps that Sydney is 2,500 meters deep so the barrier to entry is quite great. But these are the problems we all sort of struggle with. And ideally you want to make everything open and free, and democratic, because these are shared underwater cultural heritage, not just of one country, but of the world’s. But how do you do that in a responsible way to make sure in the first instance that cultural heritage is protected from people doing the wrong things with it?

[00:16:01]

Joe: Interesting. So, I’d like to dig in just because I feel like I’ve heard the stories and I’m sort of asking some follow-on questions for the folks who weren’t there. I want to at least dig into one wreck so they can experience the whole story. So, I would like to do the Kormoran and the Sydney – fascinating.

David: Well the battle between the Kormoran and Sydney was a famous action that took place off the coast of Western Australia, a place called Shark Bay, that happened in November of 1941, Sydney was a light cruiser and a proper war ship of the Australian Navy that had acquitted herself extremely well in the Mediterranean in 1940, returned to Sydney to mainly convoy duties and to protect that country during the war. And was really a loved ship because it had a namesake. So, it was really a famous ship that the Australian public took to its heart. It was the flagship of the Australian Navy. And it was sunk in a battle with a German raider. Now a raider is also a war ship but disguised as a merchant vessel. So, from the outside you can’t tell that this is a ship that could destroy you. And these two ships came across each other and in the process because the Kormoran held that disguise and actually sort of drew Sydney towards her even though Sydney was a superior ship, faster, stronger, better armaments, better armor protection, the element of surprise allowed the Kormoran to gain a very early and decisive advantage.

And literally within the first sort of minute and a half 50% of Sydney was destroyed. Their A-turret was gone, B-turret was gone, it was hit by a torpedo, the bridge was destroyed, hundreds of men were killed. And then over a five-minute period of that battle it was hit dozens and dozens of times by all sorts of heavy guns. And 70% of the crew were killed in that short of period of time. So, it was really quite rare, ship to ship actions, in World War II of that nature at literally navel equivalent of point-blank range are rare. Now this was extremely rare and it’s the only time that a raider sank a ship like the light cruiser. So, the end results, all 645 Australians died even though the German ship sank because it was hit, it had to be scuttled. Most of those men survived and the Australian public didn’t understand why Sydney was lost, and why all the people died, and it was a ship that had to be found.

[00:18:22]

Joe: So, the raider ship – I didn’t want to go too far passed that because that’s interesting, I’ve not heard that before. So, they’re basically just a tactic of camouflage to draw boats in. And when you get a boat that close, again, I guess it’s unique, so there’s probably not an explanation for it. But didn’t they know it was highly likely they were going to go down too when they were battling such a big ship?

David: Well, yeah, the Kormoran were frightened by the fact that they could be sunk. And that’s why as soon as they saw Sydney they ran away, but Sydney was faster and caught up to it. And the captain, that was his great fear that he would run into a ship what he called of the Grey Funnel Line or the Grey Navy, most war ships are painted grey. So, his first priority was to make sure that he didn’t engage and battle with a war ship. But he had no choice because he was caught up. And then his only option then was to get this element of surprise. And actually, when Sydney was right alongside Kormoran and they were exchanging signals the Sydney asked Kormoran for a secret call sign which they did not have, which as this disguised merchant vessel it should have had. And the captain turned to his first officer and said, “Do we have this secret signal?” And he said, “No, we don’t. We don’t know it.” And he said, “I guess you only die once.” And then he gave the order to de-camouflage and fire. So, this was last option for them.

Joe: Wow. And the reason you know that is because as you mentioned they decided at this point they had mortally wounded the Sydney, but they were able to off-load a lot of their sailors and make their way to Sydney where they became prisoners of war for what I think you said seven years?

David: Yeah, they were actually six combination of boats and life rafts. Six of them either made it to land in Western Australia, not Sydney, or picked up at sea, 320 men, and they spent the rest of the war all the way into 1947 beyond the end of the war because they had to be repatriated back to Germany and they couldn’t find a ship. They were low priority then so they could find a ship to send them back. So, they spent at least six years in Australia before they returned home.

[00:20:18]

Joe: And during their time in the POW camps there was an investigation that went on. And so, you were able to start collecting the data, the accounts of it to aid in your search. How did that process go?

David: Yeah, there’s an enormous amount of information because the Royal Australian Navy wanted to find out what happened. And they deposed all the men, they took testimony from them, questioned them multiple times. All of this was recorded information, it all exists in the archives even to the point that in the POW camp they set up a secret room and recorded conversations between the German officers. That was recorded and the intelligence officers that watched all of that happening, I had not just their official accounts, I even found their private accounts, what they thought had happened. So, literally every scrap of information I could find. Ultimately, I think it was nearly 3,000 individual documents I uncovered. It takes about four or five linear feet in my library of all the information that I discovered. And that had to be sifted through and picking out these clues. Navigational clues, but also between the action, what happened between them.

Joe: And we’ll get to the one key element that you found which is still one of my favorite parts of your talk, but help me understand why it would have been such a mystery? I mean, as you look back on it, you know, we’re sneaking around, Sydney came up on us, we had no choice, we fought them, why would that be such protected information that it would take you this many years later? And finding that magic clue in Germany to piece it altogether. It seems like the guys there would have been like yeah, this is what happened.

[00:21:50]

David: Yeah, and that story had been told at the time, but the Australian public didn’t trust it. They simply did not understand or accept that Sydney could be lost this way. That the Captain Barnett could have made such a fatal tactical error by coming so close to the raider. And to be fair to Barnett he wasn’t the first to have done it, others have done it and nearly lost their lives. But he made this fundamental error. People didn’t want to believe it happened and that was it. And the government made the mistake of releasing it in a way that there was this vacuum of information over a period of a couple of weeks before the public were informed. It was several days before Sydney was lost before the Navy even knew that it was lost. Then it was even more like 10 days before the government even announced that the Sydney was lost. Normally when a capital ship is lost like that they conduct a board of inquiry. There was no board of inquiry. So, for all these reasons there was this vacuum of information and understanding. And once you have that, conspiracy theories come in. And those conspiracy theories have a life of their own. And that’s why ultimately it was the greatest naval lost in Australian history, it then became the greatest maritime mystery in Australian history, and it had to be solved.

Joe: The greatest mystery, take that Bob Ballard.

David: Well, yeah.

Joe: I’m just teasing. And then why was there no board of inquiry?

David: No one knows. There was no documentation whatsoever. I think if I want to speculate the Navy knew that Barnett had made a mistake and maybe they didn’t want to go through with the process of a board of inquiry where he would be found culpable in writing that would damage his legacy. He died, you know, but still damage his name and legacy forevermore. It was a very difficult time during the war. Shortly after we had Pearl Harbor. And so, it was a bad year for the Royal Navy, for the Royal Australian Navy, and for America, and people were reeling. If there was any time in the war where people feared that Germany and Japan might win was 1941. And possibly that was added to the reasons why they didn’t go through with the board of inquiry because they had more important things to worry about.

Joe: And one of the German survivors was the captain of the ship who after his time in Australia as a POW was returned home. You said that he went to live with his nephew and you were able to go visit his nephew and found an interesting James Bond style piece of evidence there.

[00:24:12]

David: Yeah. Now, to be fair to other researchers that were involved with this, that dictionary was known about. But it wasn’t really thoroughly examined to the extent that we examined it. So, I got a lead that Detmers’s nephew lived in Hamburg. And I had some contacts with the Germany Navy because of my work on the Bismarck which I did with the permission of the German government. So, I put out my feelers and said, “Listen, does anybody knows a chap named Hans, the nephew of Captain Detmers roughly in Hamburg?” And within a week the answer came back, “Yes, we’ve located him.” And then I contacted him and then flew to Hamburg and personally was able to inspect the dictionary. And we found this account under the bridge, but also the account for the engine room. People didn’t even know about that; we saw that for the first time. And then it was a process called de-dotting, transcribing those dots putting them into Germany language. That wasn’t a coded account, that was a straight German language account. And then comparing that to other accounts. So, that was the forensic detective work that I, myself, and somebody else did that together.

Joe: So, he was given a German to English dictionary when he was a POW and he actually went through it in lieu of writing the letters he put a dot under each letter in the dictionary. So, if I needed a T, then the next T I put a dot under it. If I needed an H, the next H. And then put hundreds and hundreds of dots. And so, you feel that – Had nobody taken the time to go through and take all the letters and the dots out?

David: No one had ever done that before. I mean, yeah, he had this dictionary with him the entire time, nobody found it, and he was searched multiple times. As a matter of fact, one time he escaped. And from that master account in the dictionary he created a coded account on paper, put it into his jacket, sewn it on the inside of the jacket so nobody could see it. And he was captured and they found that account. And that account became part of the record. And we had that decoded and compared.

[00:26:06]

Joe: So, you had found the cipher for that code? Wow.

David: Yeah, it was a fairly simple code. He wasn’t a coding expert; it was a fairly simple one. But even to the point that original was missing and we relocated it in Australia, and a family had it, it was the family of the intelligence officer. And these are the things, these clues get disseminated, dispersed in different locations. You have to track all these people down. So, ultimately, we found every single account that Detmers created or was indirectly responsible for and compared them against each other. And just like a detective you see they question somebody multiple times asking the same question multiple times in different ways to see if you get the same answer. That’s a test of credibility that people give you the same answer.

Well, I’m applying the same principle to written documents. If he writes the same thing multiple times over a stretch of period, including things that he thought the Australians would never see that was only for his eyes, or for German eyes, you know, that increases your credibility, your belief that he’s telling the truth. A lot of Australian people didn’t believe that. I had quite a bit of experience using the records of German Naval officers and I knew how good they were. And I got the measure of Detmers as a man, as a commander that he would put together a correct account. And that was the strength of my conviction, but I had to convince the Australian Navy and the politicians that they had the same confidence as me. That I would be able to go out there and find the wreck based on that information.

Joe: That’s fantastic. Can you talk a little bit about the stakeholders? I just can imagine from obviously the relatives feel about this effort in some way that the government does, the television people feel about it in a really different way. And then you look at the actual tangible pieces. I mean, there is so much value just from a collectors standpoint that it’s created literally in every story that you tell. You know, right now I have the urge to go to a museum and see the piece of paper that you talked about that the intelligence officer’s family had. And to see this German/English dictionary. And so, there’s so many counter, just all the different interests that must come together and sort of you’re at the nucleus of all of these different interests.

[00:28:18]

David: Yeah, exactly.

Joe: How do you manage that? Where is that piece of paper now? Did it make it to a museum? And is that go in a Germany museum? Does that go in an Australian museum?

David: You mentioned the dictionary, how valuable that dictionary is in terms of its place in history. When I wanted to go to Australia after I had done all my research and I was invited to conduct a launch of this expedition. The public were going to be there, we’re going to be making an announcement in the press with the media all there about the launch of the search. I brought that dictionary with me. But that dictionary was so valuable, we couldn’t ship it. I actually flew Hans from Germany to London. I picked it up from him personally. It was the first time he had ever been in London. I paid for his trip to come over. I took it myself, brought it to Australia, nobody knew I had it. But when I was able to show and picked up my hand and say to them- You know, the first question is, “Why are you so confident?” And I said, “Here’s why I’m so confident. This is the master account.” And that one, I don’t want to call it a trick, but one way of presenting that information in person physically to people changes their minds. They can see it, they can fixate on it, there’s a tangible proof that this guy knows what he’s doing. There’s tangible proof that this actually happened, that this isn’t all made up, you know?

This isn’t smoke and mirrors. And that had a huge impact bringing in the dictionary there and springing it on everybody. And then I had to return it the same way to make sure that it got back to him. And ultimately that will be donated to a museum in Germany, that’s where it will stay. So, yeah, I’m in the center of all of that. And some of these projects the threads that go out from me, you know, dozens and dozens, family groups, survivors, permission from both Navy’s, the Australian Navy, the German Navy, my technical teams, my sponsors, television companies, all of that. And I’ve had that experience a number of times. You really wouldn’t be able to manage that unless you had been through it. Initially early in my career it was baptism of fire, but I’ve done it a number of times now with Hood, with Bismarck, with any of these big shipwrecks because as you say there are so many stakeholders, and it’s a very, very sensitive thing. You know, generally in almost all of these cases there’s high loss of life. And so, you have to first and foremost have those people who have the moral authority or the ones who lost loved ones in the center of your mind about everything that you do.

[00:30:41]

Joe: And I would assume because of that with the emotions there’s going to be sort of winners and losers along the way. And how much rage and anger do you get on any large project based on the folks that didn’t get what they wanted?

David: Well, not too much. I mean, you try to do it in the least controversial way. You don’t want to disturb people about it, you want to bring people along, you want to bring stakeholders along, make sure everybody is involved. And I guess where is the best example of that? The recovery of the bell of Hood. When we found the bell of Hood not for a second did it come across our mind that we were going to touch it or recovery it in 2001. We were at sea in the middle of the North Atlantic and we just saw it. And it was remarkable, but that was it. We didn’t know that everybody in England were debating should they recover it or not? People were writing letters to editors, they were on the television, radio, all talking about it. We had no idea. And that was in 2001. And that idea had to sort of percolate, and gain traction, and gain acceptance about the possibility of the recovery of the bell of hood. And even Ted Briggs himself, there were only three survivors, he was the last who was alive, who in my mind had one of the greatest in terms of moral authority what we did. I would never do anything that would upset Ted. So, it was only until a couple of years before he died that Ted came to me and said, “I’ve given a lot of thought about the bell.”

[00:32:04]

And he had given a lot of thought about whether we should even find Hood because it’s a little bit of a Pandora’s Box. Once you open it you can’t uncover it. It’s found, it can’t be unfound. So, we had to do that very, very carefully. Bring people along, explain to them why we were doing it, where it would be held. And we went out to old families who were connected to it and asked them, “Do you think this is a good idea? If we recovery it, where should it be presented?” And by doing it slowly, carefully, thoughtfully, you know, you reduce the number of people who are upset by it. Now it’s not unanimous, you know, there will always be people who are so grief stricken they can’t get over the fact that something happened 70 years ago. They’ll never get over that. But you do your best with that. And overwhelming people are very positive about Hood’s bell. And then once we found out what it was, there’s no question about it, it was the best thing that anybody could have done.

Joe: It’s a wonderful story. How does that conversation change when there’s precious metals on board? I noticed that none of your ships that you went for had that in play, but obviously, again, there’s the Tampa company that will find 10 quadrillion dollars in gold bullion or silver. And then is there sort of a divide between the outfits that go after treasure and those who are going after information? Or?

David: Yeah, there’s huge divide. There’s almost sort of three sort of camps. And it’s very controversial, it’s very combative. This is where the secretive element comes into play. There’s one school of thought that certainly for historical shipwrecks, and that’s fairly well accepted, and historically where do you set the marker? 20 years? 50 years? 75? Well, the communities mainly archeological communities set it at 100 years. There’s rules and legislation in place, accepted practice about 100-year-old wreck that that is cultural heritage shared and that should not be disturbed or exploited commercially. You can’t take bits of it, sell it, keep it in your own possession and things like that. And every country is very difficult. You have to understand the legalities. It is a minefield of legal uncertainty because there’s various jurisdictions whether it’s in state waters, territorial waters, open seas, blah, blah, blah. That’s one. At the far extreme at the other end there’s treasures hunters, they are there to find shipwrecks, mainly ones with precious metals, gold, silver, antiquities, gems, that sort of thing. And generally, those are all these older historical shipwrecks.

[00:34:25]

Well, that puts them into direct confrontation with the archeological community. Which, frankly, wants to outlaw and criminalize what treasure hunters do. And that’s the sort of two extreme camps. In the middle there is ships that sink with commodities that are not historical, that are not 100 years old, there’s nothing special about them, nothing unique about them. A ship could have sunk two weeks ago, and if it sinks with 5,000 tons of refined metal, copper, tin, nickel, cobalt, of which is dangerous to get that stuff out of the ground, these things are mined. And that commodity is lost to the owner, it’s lost to society, it’s just sitting at the bottom of the ocean, you can salvage that, do it legally, there’s a legal regime for doing it. So, there’s that middle sort of area. And my company has worked in that middle area when it first started. And I personally don’t have the mindset of a treasure hunter, I never wanted to get rich finding gold, and silver, and things like that. Treasure for me are these stories, these historical accounts. I’ve now done some work on the archaeological society even though I’m not an archaeologist. I directed a major excavation of a very famous and ancient Portuguese shipwreck that’s one of the earliest ever discovered.

And this is where my scientific training comes in. To me, the end result of that is writing a paper that’s published in an academic journal, a peer-reviewed journal, so it’s shared with people, the artifacts are in a museum, and people can see it. So, you know, it’s where do you fall on that sort of spectrum whether you’re a good guy or a bad guy. And there’s grey areas. And the public are not aware of all of that, they just love all of it. Generally, people are drawn to the ocean. Frankly they are also drawn to disasters. You know, everybody is intrigued, curious, about what happened, and that’s why these ships are lost. People who are drawn to beautiful objects, they are drawn to technology. And they don’t quite understand the battlefield of shipwreck salvage, or shipwreck discovery. And that is a difficult area to navigate and still have some respectability at the end of it. Keep your reputation intact.

[00:36:34]

Joe: Wonderful. I’ve enjoyed the conversation. I would love to finish up by talking about Paul Allen. You know, a very interesting figure and a lot of stuff he brought to the world, passed away in the last couple of years. Can you just talk about your experience with him and sort of what you know that he’s done and given to the world of recovering some of these things on the bottom of the ocean?

David: Well, Paul was a remarkable man. And his legacy will live on forevermore and not just in the area of shipwreck exploration, but the Allen Brain Institute, his work in conducting census of wild African elephants. You know, he had a huge role in solving the problem of Ebola two years ago. I mean, countless, you can spend all day talking about what Paul’s legacy will be. And it really started as a personal enjoyment. He was personally interested in World War II. His father served in World War II. He loved the water, I mean, he had these expedition yachts. He spent a lot of his time on the water diving underwater. And he had the wherewithal to be able to build an expedition yacht with the sonars and ROVs that we used to find and film these famous shipwrecks. And I was ultimately hired by his organization, Vulcan, and I worked with them over a period of six years doing a number of projects of which the location of the Imperial Japanese battleship, the Musashi was probably the biggest one. But Paul, as I said earlier, also allowed us to recover the bell of the HMS Hood.

[00:38:00]

So, when I talked about him I wanted to make sure that the last slide was in memory of him and now his legacy lives on because there’s a ship that is still finding wrecks in his name, in his company’s name, and may that continue. So, you know, it’s quite an amazing thing to have somebody who has the wherewithal for his personal enjoyment doing these incredible expeditions. But it touched so many lives. Every ship that he locates still will be hundreds more people that have an interest in it. And through the internet now they can all see it. And that’s true democratization of the seabed. Nobody can buy these tickets, you know? A ticket to dive in the Titanic is a $100,000 or something like that. A ticket to see the wrecks of some of these great wrecks you have to travel around the world, you have to dive. You know, nobody can afford that, Paul could. And he’s allowed that by sharing it publicly to people. And that’s a great thing that he’s left.

Joe: Wonderful. And he gave one of those rare second chances because it was two trips, right? To get the bell up?

David: Yeah, not many people would have done that after the first failure. And it was the last time I saw Paul. We were there together. And when the bell was rung by the Princess Royal, it was one of the nicest things. The only people who were left from Hood who were still alive had served on Hood before they had died. And there were three of them, and their ages were 97 years old, 101 years old, and a 103 years old. And I was able to take Paul and introduce him to these men and really make that connection for him. And they were delighted to see him and he was really touched by their appreciation for what he had done. And that was the last time that I had seen him. So, we shared that great day together and it’s something that I won’t forget. And sadly, now two of those men have died, one is still alive. But it was a special moment in their lives as well.

Joe: Wonderful. Thank you for your time, thank you for your stories, thank you for your good work. And we’ll keep watching.

David: Great, thank you.

Transcription Ends [00:39:58]

0 Reviews on this article

About the host

Joe Hamilton is publisher of the St. Pete Catalyst, co-founder of The St. Petersburg Group, a partner at SeedFunders, fund director at the Catalyst Fund and host of St. Pete X.