{{QUOTE1}}

The Florida Orchestra’s Pastreich leaves his legacy through community

In July, Michael Pasteich announced his plan to step down as the executive director of The Florida Orchestra after 11 years of leadership that sparked immense growth in the organization Pastreich met in dire straits.

When Michael Pastreich took the helm at the Florida Orchestra in 2007, the organization was $3 million in debt. That may not seem like a staggering figure to some – symphonies across the country have been declining slowly as attendance has continued to lag. People just don’t seem to be as interested in seeing an orchestra as they once were…

According to Pastreich, the $3 million debt was more than a small problem – in fact, having to borrow any money at all was the signal of a serious predicament for the organization. “Orchestras are cash rich,” said Pastreich, “By the time the season starts we have all of our subscription money in the bank, we have most of our sponsorship money in the bank, we have all this money for stuff that hasn’t happened yet. So if an orchestra gets to a point where it actually has to borrow a penny, they’re already deeply in the hole.”

And deeply in the hole they were. At the start of his tenure, mid-season, Pastreich eliminated $1 million of the organization’s debt, making difficult decisions at every turn. What he didn’t expect was the reception that the board would give him at the proposal of a plan to tackle the problems facing the organization – “I think I’m reasonably good at managing a board room,” said Pastreich. “This meeting was bedlam.” Though his plan passed by a narrow margin, over the next six months all but three board members resigned.

But the plan also attracted the next three board chairs to the organization. “What I had not counted on was what a filter that plan was gonna be for the organization,” Pastreich commented.

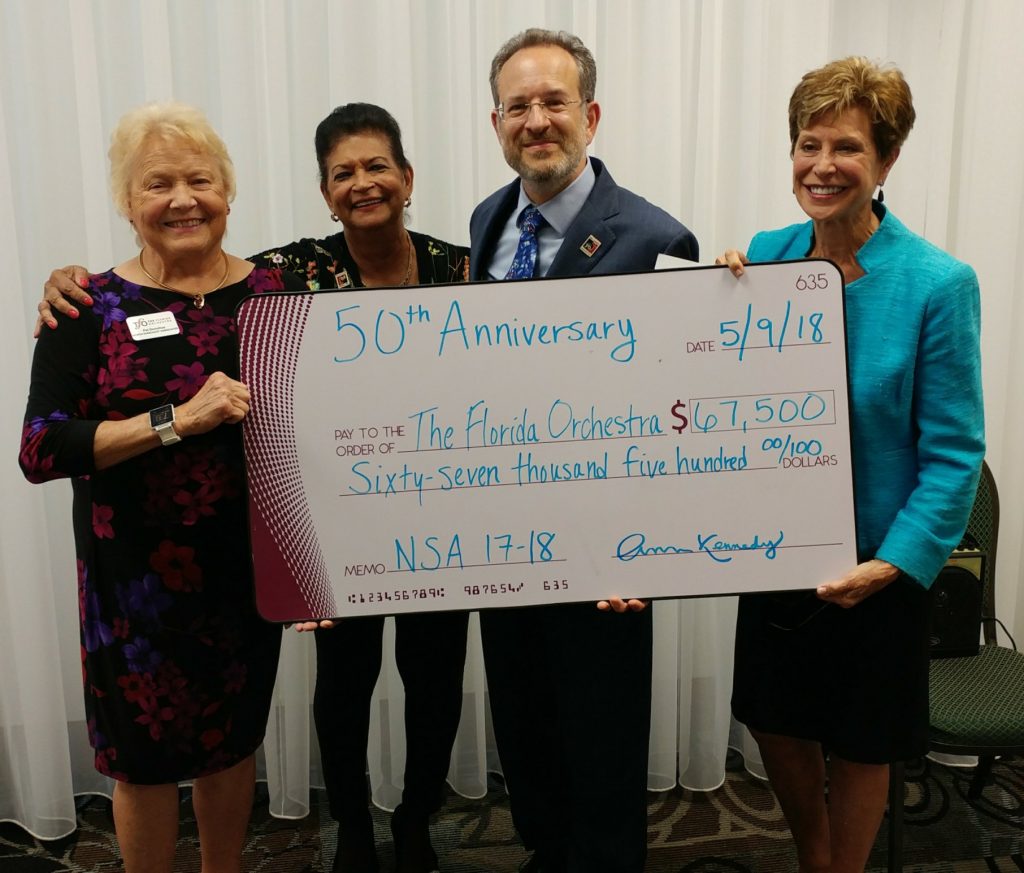

Since that time, the Florida Orchestra has seen major growth, much of it attributable to Pastreich’s plan and the direction of the impressive board that he assembled. In 2011, he reduced ticket prices to a range between $15 to $45. By lowering ticket prices, Pastreich has seen the orchestra’s audience change – attracting a younger, less predominantly white assembly. Attendance increased dramatically, peaking at a 49 percent increase in the orchestra’s 50th season.

But success was neither all about the music, nor all about the revenue for Pastreich. “My drive is to figure out not how do we make the greatest music possible, but to ask the question, ‘To what end are we making great music?’ said Pastreich. “Music in itself can’t be the goal for me.”

Those ends have included reaching wider audiences through multilateral efforts. The orchestra has taken on eclectic programming, curated pop-up performances across Tampa Bay, and made an effort to reach into communities.

One such end is the partnership the Florida Orchestra has made with the Carter G. Woodson African American Museum. Located next door to Jordan Park, just off of the Deuces Live Historic Main Street, the Carter G. Woodson serves one of the poorest neighborhoods in St. Petersburg.

The chamber series, underwritten by one of the Florida Orchestra’s board members, utilizes a pay-what-you-can model and all proceeds go toward the Woodson Museum. The series not only brings music to a traditionally under-served neighborhood, but also encourages the traditional audience of the orchestra to venture into places they may not otherwise go.

“So it’s an example of yes, we are making great music,” said Pastreich. “People who go to the concerts, consistently the feedback is that it’s a phenomenal experience. For me, we’re harnessing music to impact the neighborhood in a way that nobody but an orchestra possibly can.”

{{QUOTE2}}

Table of Contents

(0:00 – 0:52) Introduction

(0:52 – 5:24) Michael’s Roots and the Love for Music

(5:24 – 7:57) Classical vs. Contemporary Music

(7:57 – 9:56) Impact of Classical Music on People

(9:56 – 19:57) Michael’s Career

(19:57 – 29:37) Recruitment and Leadership at the Florida Orchestra

(29:37 – 40:23) Creating a New Perspective of the Organization

(40:23 – 42:19) The Role of Finance in a Non-Profit

(42:19 – 46:04) Shaping a Board and Board Philosophy

(46:04 – 51:22) Endowments

(51:22 – 55:13) Innovation and Symphonies

(55:13 – 56:58) Michael Francis

(56:58 – 57:39) Conclusion

Full Transcript:

Joe: Joining us today for SPX. We’re welcoming the CEO of the Florida Orchestra, Michael Pastreich. How close was I?

Michael: Perfect.

Joe: Thank you.

Ashley: Right on.

Joe: Well, my job’s done, going to you, Ashley.

Ashley: [laughing] Wait, what did you just say?

Joe: I said my job’s done. Right? I got the name.

Ashley: Oh, yes, and then I will unveil all the questions. So good to have you here.

Michael: Thank you so much for having me.

Ashley: Well, why don’t we start from the very beginning? And Michael, I think that people who watch the Florida Orchestra have seen a considerable evolution of your organization since you’ve taken over and I am sure there are a lot of variables to how that came about, but one common denominator is you and one of the curiosities that many have is where all of this originates from, from an experiential perspective. So maybe give us an insight to your upbringing and where this love of music came from.

Michael: It’s actually – that it turned into the love at all is interesting because my father was a symphony manager, he did exactly what I do. I was born the week after he started with the St. Louis Symphony, then he was in the San Francisco Symphony for a very long time. And I, growing up I despised classical music and despised is a very mild word. If I woke up in the morning with that stuff blaring through the house I would be in a dreadful mood for the day. All my memories of concerts as a child are of my mother hitting me and telling me to sit still. And then high school came and my first day of school in second class, freshman year, I made friends with Irfan Mirdad(?) and he thought it was really cool that my father worked for a symphony and asked whether we could go that weekend. And I said, ‘Sure.’ And then the next weekend he wanted to go again, and I’d say within a month I’d fallen in love, and I would say I virtually never missed a weekend of concerts since then.

Joe: Oh.

Michael: I’m not a musician, I studied trumpet for a year in the third grade and the teacher told my father not to be sadistic and that was the end of it, I have no ability. But I have fallen very, very much in love with the music.

Ashley: So can we talk, really just touch briefly on your original disliking of classical music? Is there–

Joe: Sounds like it’s more a dislike for having to sit still and be quiet than it was for the music itself.

Ashley: Well, I’m wondering what you would attribute that to. I don’t know if it was when you came of age or I don’t know if it’s something about the music that’s unearth an existential angst?

Michael: Yeah, I think it is more…

Ashley: Maybe I’m projecting this onto you.

Michael: I think I was being asked to listen as an adult when I was a very hyper, dyslexic, failing student – who was getting into more trouble for stealing and breaking windows and fighting than anything else.

Ashley: Got it.

Michael: It wasn’t what I was there for.

Ashley: What the music brought up in you, it wasn’t what you were listening to per se.

Michael: Right, yeah. I think it was just… I shouldn’t have been forced to have that much music all the way.

Joe: So you’re saying the lesson that Ashley is projecting is that she needs to start listening as an adult to the music. Could that be?

Michael: Yeah. It’s interesting. I used to think that if you didn’t go along with music on some level you weren’t gonna transform to it, you couldn’t resonate with you older. And even as I started to see exceptions to that, I continued to tell myself that. But I think especially now as we’re launching our community engagement activities, right? And as we’re really trying to figure out how do we serve people who have never been to the concert hall, I’m amazed at the number of people who are coming to the orchestra quite late in life. The transformation that I’ve seen many, many times is really I think been the most tender transformation that I’ve seen is I’m amazed how many people in our audience fell in love with the orchestra after they lost their life partner. So these aren’t young people, alright? These are people in their seventies who were not deeply rooted in the orchestra. Somehow, they went to a concert in that period of transformation and we became all important to them. Symphony has a magical power that I think I’ve only really started to come to appreciate in the last two-three years.

Joe: Can you articulate how you began appreciating it?

Michael: I haven’t lost a life partner, so I can’t tell how the music has that impact. But as I talk to people about it there’s a voice that the symphony has that draws them in. I don’t know if it is the quiet space, the magic combination of sitting quietly focusing in a communal activity. There’s no other experience like a symphony to have a profound intellectual journey that is entirely your thoughts reacting to the sound and being influenced by the sound around you and at the same time doing it with a lots of other people.

Ashley: Maybe that’s why it inspired existential dread in me in one point in my life, because maybe at that age I was introduced I didn’t understand what plane I was existing with the music on and maybe as an adult I should probably per Joe’s advice take back into that form of art. But you mentioned something about appreciating artists of your time and in the relationship to music. With the assumption that you have a different appreciation for music that hails from artists that are living and coming of age during your time, do you think part of the reorientation to classical music is because we haven’t grown up with these artists and we haven’t had a life in tandem with them and their own reality that we aren’t innately connected to them? I could’ve asked that differently.

Michael: When I listen to Beethoven, who is 250 years old next year, when I listen to Beethoven’s Seven, the second movement, it has a longing, a quiet exploration of all that is sad in me, that speaks to me better than anything written today. And when I listen to Michael Daugherty’s Red Cape Tango, which was written now, maybe 15 years ago, there is a joy and a fun of it that speaks to me just as well but in a different way. So that the great thing about literature, whether it’s a symphony or whether it’s Moby Dick or whether it is Georgia O’Keeffe, literature is timeless, and Iliad and the Odyssey virtually disappeared from the Earth for a while, but then it came back. Beethoven’s violin concerto entirely disappeared, it was 50 years from its premiere to its second performance. But then, great literature, it got its roots again and now it’s undoubtedly the greatest concerto ever written.

Joe: I believe that’s one of the reasons classical music doesn’t exist in people’s lives like that, it’s because it is timeless. I think that popular music defines generations and it hits people as a reflection of that generation at that developmental space in their life, whereas that’s why you have to listen as an adult the classic music, because it’s timeless and it’s intellectual and it ties more to everlasting themes versus temporary themes that are the arbitrary themes of the decade that define us.

Michael: I think also if you think of some senses, right? Think about what you ate as a child or even as a teenager. I loved whatever it was, sugar pops and I can remember how much I enjoyed it but have no desire to hear it again. There is some really bad pop music I loved as a high school student. I still enjoy it when I listen to it today because music, you absorb it as a timestamp in a way that other senses don’t absorb as a timestamp, they become more of a memory.

Joe: What about some of the biggest… I don’t wanna say breakthroughs, but some of the biggest advancements and understandings of the human body have come in interplay between external things and internal things and how the brain works – and how much of that is part of your discussion the way classical music biologically affects the listener? And does that come up in deciding your curation or just even in the musical theory now?

Michael: It probably should. And I bet if you’ll talk to Michael Francis, our music director, he would answer that brilliantly.

Joe: Right.

Michael: When I think about what to do with music and how we should be constructing our organization, my drive is to figure out not how do we make the greatest music possible, but to ask the question, ‘To what end are we making great music?’ Music in itself can’t be the goal for me. So that I think a great example for me is our subscriptions to the Carter G. Woodson African-American Museum, right? It is a museum in one of the poorest parts of St. Petersburg, there’s interesting stuff happening on that corner and it’s a neighborhood that needs our traditional audience to come into that neighborhood. And so by starting a chamber series there we’re able to bring our audience into that neighborhood. The neighborhood is also filled with people who are unlikely to spend $45 to hear a Beethoven symphony at the Mahaffey for a variety of reasons. And with a pay-what-you-can in the neighborhood supporting a local organization the audiences are about half people from the neighborhood. And since we have a board member who underwrites it, all the pay-what-you-can goes to the museum so they can build the infrastructure throughout the year. So it’s an example of yes, we are making great music. People who go to the concerts, consistently the feedback is that it’s a phenomenal experience. For me, we’re harnessing music to impact the neighborhood in a way that nobody but an orchestra possibly can.

Ashley: And just to take it back a little bit. So you did not pursue a career in music initially. And then what did you pursue a career in?

Michael: So my studies are in silversmithing, I have my Bachelor’s from Washington University and I had a Fulbright to start my master’s in Finland, which is Finland and London are the two places to study it. And then my summer job was a forest firefighter and actually dropped out of College thinking that that would become my career, but quickly saw that I couldn’t find anybody who is 30 years old and still enjoyed it. And so I decided that that’s actually my first two years in College were… I was an okay student. I think I came back from my college dropout era a very serious student, I was at a transition point.

Joe: So staying back – silversmithing and firefighting and then there was music. What were some of the biggest memories you have of interacting with your father’s, interacting with the orchestra that still play in your life today?

Michael: So for my father I would say that I didn’t see a strong differentiation between home and work. He is a brilliant person, his symphony was central to who he was, his shirts all said, ‘San Francisco Symphony’ or ‘St. Louis Symphony’. There was paraphernalia all over the place and we went to concerts regularly. And so when he had me during the day for whatever reason I would be brought to Powell Hall, St Louis Symphony’s concert hall and put in the box office with Ann Rice, the box office manager. And my job would be to take the ticket stubs and put them in numeric order or count stubs or whatever needed to be done that a six or seven or an eight-year old could do. Later in life the St. Louis Symphony had a fundraiser, a gypsy caravan which was sort of a big giant garage sale in a parking lot and I would help with those. And then by the time I was in high school, San Francisco’s Symphony, both my freshman and senior year, had negotiation with the musicians and so I got to help out with those negotiations. I wasn’t at the table, but he had possibly the greatest team of department heads in the history of that industry at that era. And so I got to be a part of the caucuses. And then when they would go on to negotiate my job was to type out the words that had been agreed onto and then Xerox them, so they were about the same size as the contract, and then Xerox the contract and cut it and paste the new words into the document.

Joe: So you were writing the contract?

Michael: Yeah, and so they went then…

Joe: How old were you then?

Michael: I was in my freshman and senior year in high school.

Joe: Okay.

Michael: So that when they came out of their negotiations they would have the language all ready for them. And so I remember – I must’ve been ten years old – sitting on the balcony of my father’s apartment and talking about his general manager and the challenges that he was having. And I would say, “Well, I think you need to fire him.” And clearly, he didn’t deny I was wrong, but throughout my life he involved me in his discussions, his thoughts, he talked business around me, we socialized with the greatest soloists and artists of that time, Aaron Copland took a nap in our house. We hd a soprano die in my brother’s bed. Symphony was part of my life.

Joe: And those pieces of it, do you look back fondly on as opposed to the music which you didn’t?

Michael: I would say all those parts are just me.

Joe: Yeah.

Michael: They’re who I am.

Joe: Neutral.

Michael: And I think they certainly come in handy now. I feel as I’m tackling the challenges that we face on a daily basis I’m remembering conversations that I had with my father as he talked about it. I remember once something didn’t go well and talking with my step-mother in front of me and saying the other person really did all these different things wrong. But once I’ve done something wrong I was no longer in a place to complain. I couldn’t argue about it anymore because I, my father, was wrong. And that was a lesson that I tried to infuse into my activities on a daily basis. All the ethical challenges that he had to face then. I remember when the San Francisco Symphony back before computers, they had a box office and before computers if you turned back your ticket, it was a ticket that said $50 on and you turned it back saying, “I don’t need my ticket anymore,” and then the box office would sell it to the next person who came. And it turned out that the box office was pocketing the money, right? And it turned into a big scandal, right? And made it into San Francisco Chronicle and FBI and the whole works. And I remember at dinner time, every night at dinner for a couple of weeks the phone would ring, and it would be another employee asking if they could meet with him the next day. And I remember just seeing the pain on his face whereas we got these calls, and talking with him about how he was gonna handle it, right? And he ultimately decided that if the box office manager was taking the money and then dividing it at Christmas to all the box office employees. And the employees said, “Well, we thought it was the Symphony giving us the money.” And so they said, “Alright, if anybody declared it on their taxes then you can keep your job.” And so just finding a fair…

Joe: Did any of them?

Michael: No, they didn’t. And so understanding the pain of tackling these problems and of course it grew over. My father has only once taken me to task since I’ve been a professional manager and that was in my first job as executive director. I’d been there for four months and we had a director, one of the department heads – department heads were four of us – but the marketing director, who I thought was not effective and needed to not be a member of the team anymore. And so I spoke with the board member that I was probably closest to at the time and to my father-in-law at the time and asked them, “And how do you fire somebody?” And both of them told me exactly the same thing, they said, “You wait till Friday afternoon, call them into your office, tell them that they’re fired, walk with them to their desk, have them put their stuff in and walk with them out of the office.” And so the night before, just by chance that Thursday night I was talking to my father and I told him, “I’m gonna have to fire this person tomorrow.” He said, “Well, how are you gonna do it?” And I told him. And there was this cold silence and he said, “Michael, that’s a human being. You can’t do that. First, think about how you would feel if you were in their position. And second, everybody else on staff is gonna be watching how you handle this and everybody else on staff is gonna expect you to treat them the exact same way someday.” And so just having all of this infused through my life I think has really – I pull from it on a daily basis.

Joe: As you’ve taken these last few positions, how involved has he been in back and forth as far as…?

Michael: I think it’s depended on his world. When he was a manager of the San Francisco Symphony, very little.

Joe: So you overlapped? He was…?

Michael: Well he was in San Francisco and I was in Elgin at the same time.

Joe: Okay.

Michael: But when he was working full time, very little. Then he retired from San Francisco Symphony and became a consultant and seemed very interested. Then he got a job working for Philharmonia Baroque, another ensemble, and he became pretty focused on them. Then he retired from them and he started to get much more involved.

Joe: Gotcha.

Michael: Then he went back to work for ACT and that became his life. He is a pretty focused guy.

Ashley: So Michael, where were you before you came to Florida?

Michael: So before here I was in Elgin, Illinois – smaller town, just outside the city of Chicago, if you go from the Chicago loop to O’Hare you’re halfway to Elgin.

Ashley: What were you doing there?

Michael: I was executive director of the Elgin Symphony for 12 years. When I got there it was one of a dozen suburban orchestras that surrounded Chicago, and then 12 years later it was by a significant measure the second orchestra in the state. And I think there we were able to develop a few key strategies that really transformed the organization, and I think the strategies that were developed in the first few months that were then just were driven forward… I think one of the things that a board member of mine, Jerry Goldstein, expressed to me is that we had when I arrived there spoken to everybody in Elgin, and everybody in Elgin had decided that they’re gonna attend or they’re not gonna attend. And spending another penny trying to get people in Elgin to come was a waste of money because they knew what they were gonna do. When it started it was just, “Let’s go to Berrington and the surrounding communities,” and very aggressively started to build strategies that talk to them. The Elgin symphony was, I would say, an orchestra that was in deep mediocrity, so nothing bad and lots of potential if only they became great. And so I think when I got here the strategy was first to consolidate expenses. There actually the strategy was to expand expenses. And so we started to market very aggressively at first in the communities around Elgin. Twelve years later we were really trying to draw a C shape from the lake to the lake surrounding Chicago and really take all the suburbs. And I always thought we were so like a flea on the back of a dog, right? The Chicago Symphony might not have felt what we were taking but we felt what we were getting quite nicely. We saw the fastest growth of audience of any orchestra in the country during that period and…

Ashley: What do those numbers look like, do you remember?

Michael: It is about a 300% growth and a little over 300% growth over a 12-year period.

Ashley: That likely played into your recruitment over here in Florida. Would you care to share any memories from that transition and that recruitment over to the Florida orchestra?

Michael: There were two things that led me here. The first one was my wife at the times’ parents had moved to Sarasota and her brother lived in Orlando. And so she kept saying, “There’s got to be an orchestra in Tampa and I want you to go there.” And so I had told all of the recruiters that if Leonard would ever retire, that I wanted to go to Tampa. I think that the recruiter actually called very few people when the job was open because she knew that I wanted it. But then there was the other academic question of I had been in searches for other orchestras before and orchestras that were in crisis. And I noticed a couple of things. One, the orchestras that were in crisis, they never got out of crisis on the one side, and it never died on the other side. And so I had the academic question in my mind, why? Why couldn’t they break out of it and if it’s so bad they couldn’t break out of it, how come it didn’t kill them? And so I came here wondering that because I saw that the people who manage the Halls were people I could work with. The orchestra committee leadership, the people who represented the musicians were great people I could work with, the board chair Jim Gillespie was somebody that I could see that I would mesh well with. So it felt like if I was gonna jump into it in some orchestra this is probably as good a place to do it as I was gonna find. And perhaps the next logical question is, so why don’t they die or why don’t they break out of it? They don’t break out of it because it is such a big challenge to break out of it. Orchestras are cash rich, by the time the season starts we have all of our subscription money in the bank, we have most of our sponsorship money in the bank, we have all this money for stuff that hasn’t happened yet. So if an orchestra gets to a point where it actually has to borrow a penny they’re already deeply in the hole. So unless you have an executive director who has really made sure the board understood the position, they get into these deep holes without even knowing it. And so in this case we had three million dollars of debt, right? In addition to all that cash flow stuff. And so that’s one challenge, it’s a big challenge by the time you’re in crisis. Second, every community has, whether it’s here or New York or Little Rock, you’ve got the people who support symphony, you’ve got people who support cancer research or animal rights. And if an orchestra’s been in crisis for a long time half the people who support the arts don’t talk to you anymore because something bad has happened over time. So the resources to tackle it are really impossible, right? Then the orchestras that are in crisis tend to get one of two types of people. They either get someone who is incompetent and can’t get a better job, or they get somebody who is really good and that uses the job to two years later leap-frog into something else. So they can’t get sustaining leadership. Those are the reasons that they can’t break out of crisis. The reason they can’t die is that they have one primary creditor, that’s the musicians. We’ve got a contract with our musicians and that is our largest liability. And the musicians can’t allow you to die, so that if they believe, they truly believe that they have to agree to something, they have to agree to it because otherwise you get what happens in the rare case of Oakland where the musicians say, “No, we won’t,” and then the board says, “Okay.” And it’s gone, and the musicians know it. So that was my discovery and that was the question that drew me here.

Ashley: I love that. I’m glad you went in a roll there, great insights. Without knowing the numbers, because I think the numbers that I pulled from the site might be somewhat dated in terms of endowment in 18 million. It’s higher now, isn’t it?

Michael: Twenty-one.

Ashley: Twenty-one million, and annual revenue is what, 15?

Michael: About 12.

Ashley: Twelve million…

Michael: Yeah.

Ashley: I’d love to understand the magic of getting from three million in debt in funding operations to where you sit today, a 12-million-dollar organization, have to fundraise over half of that to sustain operations with over 20 million in endowment. That coming from the state of things, love to glean some of what happened under your leadership.

Michael: In the beginning and the end it’s all about the board. A great board builds a great organization, a weak board doesn’t. We early on recruited a board member, a man named Howard Jenkins who is, if you read “Good to Great” the description of the level five leader, Howard is I think the personification, right? He does not have an overbearing personality. The only time you see his eyes really light up is when you start talking about Publix, his company, or when you talk about his grandchildren. And Howard never told me how to do anything. I don’t think it ever occurred to him, even in areas where he clearly knew more than me, that he could or should tell me how to do something. But he would tell me, “You gotta do something,” right? And I remember I arrived as I said earlier, a week before the Dow hit its high, right? And so when I first arrived we aggressively came in and removed about a million dollars in the first year, mid-season and made a bunch of really hard decisions. And then a year later a recession hit, right? And I remember talking to Howard who at the time was giving a lot of money, and I said, “Howard, I don’t think that we can cut any more.” And Howard said, “Well, if I stop giving you a million dollars a year you’ll figure out how to cut.” I’ve never again said you can’t cut. I’ve talked about the price of cutting. Because every decision you make has consequences, right? And with the orchestras I find that dealing with crisis, the hard thing is buying time. Because if you have to make a decision that you’re gonna implement over five years you can probably figure out how to do it painlessly. If you make the exact same decision but it has to be done next season or within this season you can go into rupture. And so we had to build plans that let us think longer term. And I think probably my largest surprise that happened after I got here was I arrived in October of ’07, in May of ’08 we brought forward a plan for how to tackle the challenges in front of us. This is before the recession hit. And we brought it to the board meeting, I think I’m reasonably good at managing a board room. This meeting was bedlam and unfortunately Howard came there, and he saw the bedlam which was, I think, unfortunate in many ways. But the plan barely passed, it only passed through the power of a binary vote and within six months all but three board members had left the board. Some left because they thought it was too draculian, some left because they thought it was only looking at revenue and pie in the sky, people left for a variety of reasons. It also was clearly how we attracted our next three board chairs. What I had not counted on was what a filter that plan was gonna be for the organization.

Ashley: Was there a response or reaction more about the plan for the operation itself or for their expectations as board members, i.e. if there is a fiduciary expectation or some other element that directly affected them?

Michael: We hadn’t yet, it would be a couple more months before we started talking about board minimum gifts, so we hadn’t yet tackled that aspect of it.

Ashley: So your loss of three remaining board members at that time?

Michael: No, those three are all still on the board.

Ashley: Right.

Michael: Greg Yadley, Jim Gillepsie and Suzie Betzer have been here through hell and back.

Ashley: God love them!

Michael: The board at the time, I think a lot of their loyalty wasn’t to the orchestra, right? A lot of them were… they worked for a corporation who sponsored us and so their CEO told them, ”Go be on the board.” So to some degree they were there to watch out for the interest of their corporation more than to look out for the symphony. In some cases they were people where the musicians went and said, “We need somebody to look out for our interest, can you please go join the board?” And so there were a variety of areas. I think maybe much like what I see in the world right now, when you go into crisis people turn into caricatures, that when you’re in a crisis the board becomes this cold, hard board and the staff becomes this bureaucratic entity and the musicians become whatever musicians become. And only by breaking out of crisis and giving people a chance to breathe and relax and become a family can you turn these caricatures into human beings. Right? And so I think that this filter is the people who were invested in their caricature didn’t feel comfortable anymore. And then we were able to bring on human beings, right? And this is no longer true, but for the first almost decade every single board member who came on was a subscriber before they became a board member. So we brought people who profoundly loved the music and who have great business acumen and they brought them both together. And I’m probably talking too long but I think this is important, so I’m gonna stick with it for a moment. Because I’ve seen boards with great business people who aren’t tied to the mission of the organization and that fails. I’ve also seen boards with people who love the orchestra and don’t have an ounce of business acumen and that’s absolutely no better either. You need a board of people who really live the mission of the organization and can really understand business implications.

Ashley: That was great. I’m curious about, in the moment when you lost all but three board members, you were very new to the organization and now you have the perspective to look at them as caricatures or have a perspective and then to see the value in what you’ve now created, a – not family, but can you describe how the emotional resilience to – not knowing what was going to be the ultimate fallout by losing nearly 100% of what had been built – Did that bring you anxiety or…?

Michael: I had the huge advantage in youth of being a screw up and being the disappointment throughout my life, so that I’m used to that. It’s how I have lived my life, so I think I enjoyed it, yeah, I enjoyed the battle and I enjoyed seeing the difference from day to day.

Joe: Did you enjoy the battle because you had a vision that you were fulfilling, or did you have a generally right path you knew you were on and it was more of a tactical enjoyment?

Michael: Yeah, I think the latter. The whole concept of vision, I don’t know what vision is. We talked a little before we went out and turned on the microphones about Jim Collins and “Good to Great”.

Joe: Right.

Michael: And I’ve read all of his books multiple times. And in the beginning, his first book, “Built to Last” he talks about vision and he talks about BHAGs and all sorts of what I think is rubbish. And by his later books vision isn’t talked about at all anymore. I think in his book “Good to Great” he comes up with the hedgehog principle, which to me seems to be a pragmatic replacement for vision, right? And the hedgehog, it’s a nexus of what you do best in the world, what your economic engine is and what you’re passionate about. I think that in essence is vision. And in his book “How the Mighty Fall” he talked about the CEO of Hewlett Packard and the CEO of IBM who were both brought in to save failing organizations. And the CEO of Hewlett Packard kept talking about vision. This is when I concluded that Collins gave up on vision. When I asked him he disagreed with me, I still think he gave up on it. The head of Hewlett Packard kept talking about vision, and we owe you a vision, and we’re gonna build a vision, and vision, vision, vision. And clearly, she failed miserably. The head of IBM was asked about vision and he said, “Good God, the last thing we need is a vision.”

Joe: I think that maybe you’ve abandoned vision because the idea of vision is abused, not because it’s bad, innately right. And maybe it’s used inappropriately at inappropriate times so that this Hewlett Packard guy may have been correct that the last thing they needed at that time was a vision. But if you look at–

Michael: IBM.

Joe: Or, excuse me, IBM. If you look at the elements of… the three facets of passion and… it’s a bit happenstance to look at them passively and say, “What are they?” and then react to it versus what are they while you have a chance to define what they’re going to be, right? And that’s where vision plays into that. It’s sort of an internal reflection as to what’s important and what are you passionate about, but then the vision comes in in how do you mix those three elements together and what could be a viable reason to do that and what’s on the other side of that potential. And that’s essentially seen an ending spot to go towards.

Michael: I think that we have a variety of board members at the orchestra who are thoroughly frustrated to no end as I refuse to grab on to a vision. I’ve friends who I think are some of the greatest symphony managers of our era who talk in great visionary tones. I don’t.

Joe: Right. I consider myself a pragmatic visionary, I think that I know that there’s a function that I want to fulfill in St. Petersburg or there’s a position that I want to hold through my achievements or a thing that I want to bring to St. Petersburg and I don’t necessarily have general definitions and directions on how I’m executing that. And that’s fun, a lot of that is governed by the passion and what you’re best at and things like that. But I also see that I’m actively building my hedgehog, because I don’t know that you can just realize it, and have it be there, because what I want to do… I think that’s just… At the end of the day people’s existence can’t be boiled down to that one element that they roll up and that’s their defense…

Michael: Right.

Joe: …but I believe my defense in this city has to be a little bit more multifaceted and that, so I need to get the legs on and the quills on and stuff, and then I know what that is but it’s not something that’s just gonna exist as a singularity right away.

Michael: Yeah. I think, as I look at the orchestra, there are things that I pursue pragmatically that probably equate on some level to what you’re calling vision. For example our economic model is subscription model, and of course unfortunately the subscription model is falling apart in the world, but I think we’ll redefine it as frequency, total paid attendant in frequency is close enough to subscription. And so I focus on driving those numbers, which is pragmatic. Now of course the more we drive those numbers the more people we’re serving, which is missionary and visionary. So there’s some connection. I‘m a firm believer going back to Collins, in his book “Great by Choice” he talks about the 20-mile march, the race to the South Pole. And one of the people would charge as far as he could in good weather and hold up in the tent and ultimately failed and died. The other one went 20 miles no matter how bad the weather was and didn’t go more than 20 miles no matter how good the weather was. And it’s a concept that we try to pursue, so that I think in order for us to be a great orchestra we need to be more financially competitive with our musicians, right? And we need to be able to retain our best musicians, we need to be able to attract ever better musicians. So a couple of things in there. One, I’ve tried since the 2010 negotiation to have a 4% raise for the musicians every year so that things are good, I try not to give more than 4%, if they’re bad I try and push the board to give a 4% raise so that there’s this constant move. We compare ourselves with what we call Group Two Orchestras, it kind of starts in San Diego and goes down to Toledo and we’re in the middle. And when I got here it was the second lowest paid Group Two Orchestra. We’re now the seventh lowest paid Group Two Orchestra. The end of this contract my hope is that we’re the eight lowest paid so that it’s not some big vision and we’re going to charge forward; let’s just get up one notch and through there – maybe that’s vision, right? Because the goal is to become as incredible musical force that rivets you to your chair and this is one way to do it. Another one is that we say either introduce a new subscription series or grow an existing one every year. On the surface it sounds maybe not that hard, but over 12 years later, 11 years later it’s hard. And in the process, we’re hiring the musicians more, we have to invent new series so that we’re doing all sorts of stuff we would never have dreamed of a dozen years ago or even half a dozen years ago. Maybe that’s vision. For me that’s pragmatic.

Joe: I think a lot of it it’s just vocabulary, to your point.

Michael: Yeah.

Joe: And I see it as a puzzle, and when you think about a traditional puzzle you look at the box as the picture of what it’s supposed to be when you end up. And to some extent there’s some nondescript thing that is the highest and best orchestra and you know the pieces that go into that, you need the best paid musicians, you need the best curated music, you need the most impressive or best quality conductor, you want the most engaged board… Then these are all things that all feed into a central purpose…

Michael: Right.

Joe: …and the highest ideal of that purpose I guess, then, becomes what I would call vision.

Michael: And then other areas that perhaps these are vision is when you question – I think some of our hard discussion have been when we’ve questioned some basics, right? So that in 2011 we launched our accessibility initiative where we drastically lowered ticket prices, simplified packaging, diversified what we performed. And I think it was predicated on a new understanding for us that full halls had value beyond ticket revenue, right? That what we and virtually every orchestra in the country was doing is that as we needed money we raised ticket prices and if we raised ticket prices 10% and we’d lose 5% of our audience we’re up money, we’ve got more money.

Joe: Right.

Michael: Of course, you take that to the end and you’ve one person paying 20 million dollars for one ticket, and you’re fine until that person dies. And so we realized the five values of a full hall beyond ticket revenue are: One, it’s a better experience to be in a full hall and if you’re the only one there you’ll wonder what you’re doing wrong. Two, musicians play better in a concert hall, it’s an interactive experience. Three, only a third of our revenue comes from tickets, so that means 60% comes from fundraising; one could argue that we’re not in the ticket selling business, we’re in the fundraising business; in a full hall there are more potential donors. Next, our current donors feel better about supporting us when the hall is full because they see we have a future. And then finally we can fight better when the hall is better, right? If we’re having a problem with the mayor or a hall manager or whatever it is, we can look out for our interest better if our hall is full than if it’s empty. And so with the accessibility initiative where we just completely rethought how do we bring people into the concert hall? That was an interesting, a full year of conversations with the board as they went from, “What do you mean? We’re in financial crisis, our ticket revenue is going down at $100,000 a year, we need every penny we can get. How can you possibly be suggesting we lower ticket prices?” Right? And two years of the board really balking that, but… and probably using whatever collateral I had to go with the board spending it so that we stuck with it, and then within three years the board would say, “Boy, we’re geniuses, this is great!”

Joe: I’m surprised it was such a hard sell. It makes even just the five benefits that seem so obvious, I’m surprised it was such a hard sell.

Michael: Well, things that are in easy sell in a room in an academic conversation.

Joe: Yeah.

Michael: And things that are the same argument when you’re in a room with people who are…

Joe: …caricatures, yeah.

Michael: …seeing the budget rupturing and ticket revenue going down and we gotta get money.

Joe: Yeah.

Michael: You think differently, right? And so a lot of tackling the challenge is, I think, trying to figure out how do you get breathing room? And then fortunately buggaboo about a breathing room is that often when you get breathing room you slow down, right? And so how do you both fight to get a breathing room and maintain the urgency to go forward?

Joe: It’s a great point.

Michael: And we tackle that to some degree, we created urgency. For example we had a line of credit, three million dollars line of credit. We decided that any time which we get money we were gonna pay down that line of credit. So that meant that we stayed in crisis for four years, even though we were having surpluses, right? Even though in theory we didn’t have to be in crisis. But we needed the pressure, right? We needed to make sure nobody for a second thought that they could let up.

Ashley: Do you think that non-profits should be showing surpluses? Do you think that that’s… you wanna stay…?

Michael: Absolutely.

Ashley: Yeah?

Michael: So, let’s talk about the role of finance in a non-profit. So as a non-profit we’re not bringing in money so we can pay shareholders or bonuses and I think a non-profit leader should never get a bonus is my personal belief. We’re there to serve the community, to make it a better community. And finances are a tool. If you have more finance, then you can think more strategically. If you have less finance, you can think less strategically. If you’re financially strong you can experiment with innovation, you can figure out what parts of the community are being served, you can figure out how you can serve the people you’re serving now better, you can do all sorts of stuff if you’ve got money. If you don’t have money then you go from a focus on serving to a focus on survival and when a non-profit is focused on itself, right? That’s the last thing a non-profit can be focused on, right? So when you’re in a world where you’re focused on yourself you bring yourself down a deadly spiral.

Ashley: What about the donor’s perspective though? If you come to them in a state of “If you don’t help us we cease to exist,” versus “We’re doing great and we can do more,” you see a different response on the other side.

Michael: Well, different yes. But what different means is curious. Because there is no doubt that there are board members and community members who love whatever your non-profit is, where if you go in and you say, “We’re gonna die if you don’t give money,” who will make a gift because they believe in your mission and they don’t want you to die. But you’ll wear them out. They’ll do that one or two or three times and then at some point they’ll pack in the towel because…

Joe: …it’s a zero sum.

Michael: Right. And they want to support because they want to make a difference. And when you’re fundraising on a deficit it’s filling a hole. If you’re fundraising from a position of strength, it’s about vision.

Joe: You mentioned when we got to the part where you were down to three board members and that gave you a chance to really have a concept of a board and be in a position to shape the structure of the board the way you wanted and now you’ve got one of the giants in the city as far as boards go. So tell me your philosophy on boards and building and shaping and structuring them and…

Michael: So, first just a point of clarification, we never had three board members, right? There was a six-month period where board members were coming off and board members were coming on. So we talked a little bit about it earlier, I think board members have to be people who both have an intrinsic belief, a dedication to the mission of the organization and have to have a strong business acumen, and anybody who doesn’t have both of them shouldn’t be on the board.

Joe: When you look at the board make-up do you actually break it up into skillsets and try to fill a financial person, a marketing person?

Michael: No.

Ashley: So you have a board with fiduciary responsibility, then you have an advisory council if I’m not mistaken.

Michael: So we have three boards. So those are two very good questions. I’m gonna answer that one first and then that one. So I’ve heard board members say, “Let’s take a look at what we need.” And to some degree that probably depends on the size of the organization, right? If you’ve got a new-found organization with no staff, then you need to make sure you know you have somebody who can keep the books for you and you have somebody who can do the fundraising for you and so on and so forth. By the time you get to our size you’ve got I think a high quality professional staff who know how to fundraise and know how to do accounting and know how to write a press release and know how to write a grant better than any of our board members do. So then the board’s job is no longer skill-specific and what we need from our board members are thought partners. If staff says, “Hey, we think we ought to do x,” we need people to say, “Why?” Right? And when we say, “Here’s how we’re gonna do it,” then we need people to say, “That doesn’t make any sense.” We need thought partners, we need people who can take our ideas, tear them apart, push back so that by the time we’ve answered all the questions we’ve got something phenomenal. That’s what we need in our board. Yes, we have three boards. We’ve got a board of directors, a board of consultants and a council of advisors. The board of directors are the primary fiduciary and so they’re the ones ultimately if the worst happened they’re financially on the hook. They also if you’re on the board of directors you are absolutely expected to fundraise. There’s a high personal gift and you have to give $10,000 a year and it has to be personal. So that if you work for Raymond James who gives us a very large sponsorship each year that doesn’t count, right? You have to have your own personal skin in the game. You meet regularly, you meet every other month, there’s high expectations you really understand the finances. If you’re one of the directors you can never say, “I didn’t understand that.” If any director comes with any financial question any department head will drop absolutely everything and spend as much time as necessary.

Ashley: How many do you have total on board?

Michael: Thirty-eight, I believe. Then we’ve got our council of advisors. We do everything we can to make the council of advisors feel like they’re the board of directors, but they meet quarterly instead of every other month, their gift is $2,500 instead of $10,000. For the consultants actually your corporation can make the gift for you. There are some consultants who are phenomenal fundraisers, but you don’t have to fundraise. So it’s a way for us to bring our tentacles deeper into the community, to be much more inclusive and it’s about the same size group. And then the council of advisors, they’ve done their time and they want to stay on the inside, and so we meet with them twice a year, we have a good candid state-of-the-nation conversation with them.

Ashley: An emeritus board, essentially?

Michael: Yeah, largely. And I think nobody’s joined it in the last eight years.

Ashley: I’m wondering if you actually, when you talk about financials, look at the potential – for lack of a better word – windfall that could come through bequest of your current constituencies in terms of planned giving…

Joe: Don’t ask that.

Ashley: …planned giving and legacy giving and how that factors into not vision, but in terms of you could find yourself with a pretty large sum of money over the next decade or so, especially here in St. Petersburg and here in Tampa Bay. And you’re in a unique position compared with other non-profits who are dealing mainly with youth or young families. And if you look at your current constituency, you would be hard pressed not to be aware of that.

Michael: So clearly there’s about to be a major generational shift and we are clearly trying to develop strategies to make sure that we come out as strong through that as possible. We’re also moving into a world where we are finding more and more ways to serve the community that has little or no revenue, right? So that if you go back to when I got into the business as a professional, not as a kid, but as a professional 25 years ago, orchestras were about half earned revenue. Now we’re a third. So that as time goes by that that will shrink and so we’re gonna have to grow our endowments in order to make the difference. The reason is the percentage through earned revenue is gonna change a variety of things, but one basic thing is that in organizations like symphonies, like Universities, or at least Universities before they invented distance learning, is that there’s not much room for innovation to save money, right? If you work for Apple and you’re making cell phones, over time you’ll find ways to make them more efficiently or to make them faster, and so that helps fight inflation. In most forms of business innovation helps make it cheaper over time, and so inflation goes up, you find savings and so your expenses don’t go up too fast. In 1900 it took about 100 musicians, about 40 minutes to play a Mahler symphony. A hundred and 18 years later it takes the same number of musicians, the same amount of time to do the same amount of work and there’s been no efficiency whatsoever, there’s nothing to help offset inflation. And so as that happens we need to find other ways to make it so people can come. And what the orchestras have been doing and what the arts have been doing is we’ve just been raising our prices and the price of attending the arts over the last half century has gone up at a rate that dwarves inflation, so that much of the country just can’t afford the arts anymore. We found that in 2011 when we drastically lowered ticket prices, right? We knew basic economics say the lower the price, demand goes up. We weren’t prepared for the 45% increase we saw. What we discovered was that this community loves the orchestra, they hungered for the orchestra, they just couldn’t afford it. And so then we have to figure out how do we tackle that? And endowment is certainly one of the many ways. The other thing that has to offset is that I think that as a parent of teenagers I’m betting that my children aren’t going to be able to pay for a ticket what I was able to pay, and I certainly wasn’t able of paying as a young adult what my father was able to pay for tickets, right? And so we need to figure out ways to become more effective at making it so that anybody in the community who wants to attend the orchestra is capable of it.

Ashley: Just an off-side, do you have a special way of preserving… so if I’m a widow, I come and I’m mourning my husband’s passing through your art and I decide to leave everything that I own to you, are there special ways that you honor my hour legacy beyond the sustainability of your business? Have you found new and creative ways to…? If you think about capital investments or for brick and mortar, capital projects, it’s easy. You have your…

Michael: Right.

Ashley: …William Hoff on the wall and it’s there for decades, if not centuries. But how do you preserve a legacy?

Michael: So we probably try to understand what means something to you, right? So that we have endowed musicians, so then we started shortly after I arrived is our musician sponsorship program, so that if you make an annual fund gift of $10,000 or more you sponsor a musician. And all that we promise when you sponsor a musician is that we’ll arrange a lunch or dinner with that musician each year and when we have events we’ll invite that musician – which is enough seasoning for you to build the relationship that’s right for the two of you, right? And there’s some people who really go on vacations together or go to spring training every game together. And there are people who give a friendly nod in the lobby depending on what the chemistry is between those people. And there are people then who become very close and they want to endow that chair. So that’s one way to address it. There’s some people where what we do with the schools really matter to them, and so they can endow those activities. What’s surprising to me is that most of our bequests that we get are not designated at all, they are left to the organization to do what we think is the best use of them and our policy is to put it into our endowment and not spend it but then spend a little bit of interest each year. Because we see these tidal waves of new activities that we’re gonna have to go and get into in the future if we’re gonna be the servants that we have to be.

Joe: I’m surprised to when you say, this is a change of subject, the Apple example, I still feel like that’s one lane that innovation plays in. There are quite a few other lanes that aren’t product based. So it may take 40 minutes to play the piece with 100 musicians, but you may be able to heal someone’s…

Michael: Oh, absolutely! What I think symphonies do brilliantly, symphonies I think are great at figuring out what can never change. I have no doubt in my mind that in 100 years from now you’ll have large rooms with people who sit quietly and listen to a Beethoven symphony played by a group of 70 or 80 musicians. Those musicians might be holograms for all I know, and the people might have chips in their brains where they’re able to see the notes, who knows? But the act of sitting in a communal experience listening to music being played that won’t be quite the same tomorrow night, right? Because it’s a live experience. That will stay the same. At the same time, symphonies reinvent everything, right? We reinvent how we market… When I worked for the Chicago symphony back in 1990 the idea that we would play a pop’s concert at the Chicago symphony was absolutely absurd, and now Chicago is defined as the pop series. The idea that we would play the music to a Harry Potter film, if even we had imagined some movie about wizards, would’ve been absolutely scoffed at, right? But as time has gone by the symphonies have reinvented themselves, we’ve understood that we need to perform in different ways. Now we do music of video game music and I think if they are, for many of our people the most important thing we do all year.

Ashley: Isn’t that a sold-out event?

Michael: They’re sold-out events and what I didn’t anticipate was how much feedback we get from parents of autistic children. The games speak to them in a way that nothing else in this kids’ life speak. That’s something that it didn’t occur to me symphonies could do. For us until two years ago our definition of education was we’d perform music and talk to you a little bit about the music you heard, that’s what we called education. And two years ago we got our teaching artist and we started call education physically teaching teachers how to teach. Now with this prodigy program, education is we’ve got kids with violins in their hands and our musicians. Cynthia, one of our musicians is there saying, here’s how you play. So our definition of education has gone down a spectrum and I will be interested to see how we define it by next year. The lobby experience has changed, seats have changed… If you’d go to a Florida Orchestra concert just four years ago you’d go to a concert, you’d see musicians warming up and ignoring you, then you would see a librarian come, turn her back to you, she put the music on the stand and then a conductor would come and turn his back to you and conduct. Oh, and in between there a voice of God would come down and tell you all the things you’re not allowed to do. And now when you go to a concert the musicians are warming up and ignoring you as always, but then they leave the stage, they come as a group and so that the audience can applaud to them, they bow to the audience, there’s an interaction there. One of them continues to stand and asks you to turn off your cell phone, that’s the one thing they continue to do, all the other don’ts are gone, and they tell you a little about themselves, they usually compete for how they can be humorous, they build a bond, then the conductor comes down and talks a little bit about the program you’re gonna hear and then the concert starts. It’s an entirely different experience. And I think that we have to constantly be asking ourselves, how do we reinvent the orchestra, how do we reinvent every aspect of us while guarding as preciously as we possibly can the core of who and what we are?

Joe: That’s great. Let’s finish up with our beginning favorite topic, Michael Francis. What’s it like to work with this gentleman?

Michael: Michael is discipline incarnate. What I think Michael does for me when working with him, I’ve never met somebody who knows how to push for the ideal since once the 11th hour and become incredibly pragmatic. When he’s under his programming I think he’s brilliant, he thinks more holistically about programs than anybody I’ve ever met. He is not an easy guy to work with, doesn’t matter if it is how to perform tonight’s concert or what our brochure looks like. He has an opinion, he has a strong opinion, he pushes you and it’s not that he’s pushing you for his idea, he’s pushing you to do something five times better than you’ve done it already.

Ashley: Explain his charisma.

Michael: I don’t know if I can. His energy is clearly an intelligence that dwarves everybody else in the room and at the same time a humility that I think comes through his religion. He’s just magic. He can go from this imp-like humor, British humor to really deep serious conversations about the state of the world or how do we touch the soul of human beings. He is clearly driven by deep missions within himself. He can talk about his football or our football or car racing or golf or Shakespeare or Beethoven or jazz and his deep knowledge is extraordinary. And I hear it was true with Kennedy, I met Barack Obama when he was my state senator and I felt it, and I feel it with Michael. They are these rare people who have this natural magnetism and Michael’s got it in spades.

Joe: Perfect. Thank you.

Ashley: Yes.

Joe: Really appreciate it.

Ashley: Thank you.

Michael: Thank you for having me.