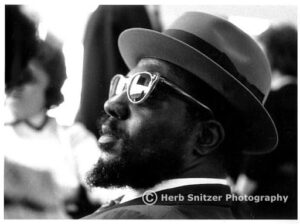

In a non-stop career than spanned more than 50 years, Snitzer – as a professional on assignment for Life and Look magazines, the New York Times and other publications – created dozens of now-iconic images of the great jazz musicians of the 1950s and beyond. He discusses his self-described job as a “visual historian,” his thoughts on photography as an art form, and why he prefers to work in a darkroom, perfecting his prints, rather than shooting things digitally. Other topics include the business of selling limited-edition prints and Snitzer’s important role as a chronicler of the civil rights movement in America.

{{QUOTE1}}

{{QUOTE2}}

Table of Contents

(00:00 – 01:10) Introduction

(01:10 – 04:21) Taking A Good Photograph

(04:21 – 07:59) The Rise of Digital Photography

(07:59 – 17:51) The Jazz Era and Herb’s Early Career

(17:51 – 22:16) Miles Davis

(22:16 – 23:52) Nina Simone

(23:52 – 27:57) Transitioning as a photographer

(27:57 – 32:52) The Photography Market

(32:52 – 36:01) Herb With Jazz Musicians

(36:01 – 36:53) Thoughts on St. Petersburg

(36:53 – 38:23) Conclusion

Joe: I’m sitting today at the home of iconic photographer social documentarian through photos, Herb Snitzer. It’s good to see you sir.

Herb: Nice to see you too, thanks.

Joe: Well, you’re most known for your photography, so let’s start with exploring that a little bit. What makes a good photograph?

Herb: Well, like any piece of art it has to touch the soul of the person. And on that level I’ve spent 60 years making images that convey this attitude.

Joe: And when you go about to start to make a photo how are you interacting with your subject matter? How are you experiencing it? And how are you framing it?

Herb: Well, sometimes in a very cohesive way where I get to know the subject that I’m photographing so many times when I was working for life for Look magazine back in the days, you didn’t have much time with the subject that you were committing to photograph. But in the jazz world which I lived in that world for a number of years I got know many other wonderful players, and it wasn’t difficult to try and find a little bit of humanity or a lot of humanity in the people that I was photographing. I love jazz musicians and jazz singers.

[00:02:25]

Joe: Sure. So, when you get magic in a photograph, how often do you know it when it’s happening because perhaps of your relationship with the subject matter, or the person int he photograph, and how often does it come to you when you’re actually developing the shots later on?

Herb: Well, developing the image that you were going after, that’s the mechanical way of looking at any art. I have to relate to the person or to the people. I have to show them my side of life. And once I was able to do that and recognize it was happening time and time again I realized that I was doing something that not too many other photographers were doing.

Joe: And you think most of that comes in the eye in the front in?

Herb: Well, it comes in the heart.

Joe: In the heart.

Herb: Yeah, I say to my young students tell me how you feel about what you’ve created. It’s not just a mechanical thing. I mean, photographers are human beings and some are nice people and others are not nice people. And it boils down to just what your thoughts and feelings are for what you are doing. Now when it was a commercial gig that’s one thing, but when it was my own feelings about things sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t, but every time I was able to deliver an image that has lasted for 60 years, I mean a long time.

[00:04:05]

Joe: Sure. You famously resisted moving to digital for quite a while, saying that it didn’t give you the same connection. When you sort of mapped that onto students and they are trying to connect with their heart to the subject matter do you feel like the proliferation of digital tools, and you know, just even the economies have been able to shoot infinite photos without having to pay for film and developing has been ultimately a good thing, and what it’s opened up in photography for the world, or something that has hurt the craft overall?

Herb: Well, commercially photography is still doing what it has done for a 150 years which is what we call the wet process. Now we have the dry process, and I don’t put a lot of emphasis on digital photography because of the quality of the result is what I am after. I am after a luminosity of paper and opportunity to contemplate when I did my developing. It was a slower process, and for me, a more thoughtful process where I get in the dark room. You know, it’s me and that enlarger, it’s me and that piece of film. And I’m conflicted with it because I come from a different generation and some of the things that are done digitally, especially with the sports photography, it’s like boy those guys are really good. They are really good, they really get the moment, but then they move on. Whereas for me I stick around and try to understand what I’ve done because a lot of it is intuitive. You know, artists are not alike. Like these pieces here they came about because of my feelings about voting, and my fear about what may be occurring on November 4th. So, this is more a tribute to John Lewis who I happened to meet in Washington one time and just was awe-inspiring to shake his hand.

[00:06:27]

Joe: So, continuing on the thread with regard to the time in the darkroom, do you think that is a valuable time developing the full photographer as an artist that you lose when you are just cranking out hundreds of digital shots?

Herb: Yeah, I think that if you have the time to think about what you are doing to understand the assets and limitations of wet photography, so to speak, it’s a wonderful quiet. It’s almost like a Buddha quiet when I’m in the darkroom. I mean, when I first started out I could be in the darkroom 18 hours straight. I don’t do that anymore. I don’t have the darkroom anymore, but I still photograph. And I can always have it processed so then what do I do with the contact sheet and the negative? You know, I’ve got to find resources that will enable me to make images which I have found in the arts center here in the Morean Arts Center downtown. They have a full wet/dark room that is just not the place to be right now, but it certainly is a wonderful venue and they let me use their darkroom facilities, which is terrific.

Joe: Jazz is obviously a big part of your canon. And you did a lot of that work on assignment. And I think before we get into looking how jazz juxtaposes against the other pieces of your career, let’s dive into jazz a little bit. One thing that you’ve remarked on previously is how hard it was for jazz musicians to just get by. And everything from the standard struggles of making a living as a musician to the racism and just the difficulty, you know, the expectation. So, as you look back on your relationship with jazz in those times, you were covering the greats – what stands out? I mean, the greats? What stands out most for you?

[00:08:34]

Herb: They are humanity. I love jazz musicians. I think that they are just wonderful people. And as a metaphor I see the music as a cry for freedom. And it started with my interest with the be-bop era and moved forward. But that was protest music, that was Dizzy Gillespie saying I can do whatever I want to do if I want to put my horn up in the air I’m going to do that. Or Lewis Armstrong, who talked down Fidel Castro with saying he is no spy, referring to himself, that I am no spy. John Coltrane and his protest music, I mean Max Roach, Abby Lincoln, all during that period of time saying we are people. And it juxtaposed right with the freedom movement. So, it was something to experience. And it has continued to this very day like Black Matters.

Joe: How apparent was it when you were going through it? Did you know you were in a special place in time? Or did you sort of understand that a little bit later on?

[00:09:51]

Herb: A little bit later on. What I was doing in the early part of my career was basically to establish myself in New York as a young photographer, documentary photographer, which I was able to do and ended up photographing for Life magazine which was a thrill all by itself for somebody so young and so inexperienced really. It was a glorious time. And musicians, they are not brain dead, you know? They really do understand life’s issues because they were always traveling. And being in the South it was like combat pay. You know, it was frightening. I remember when Brown V Board was passed by the Supreme Court in 1954. I was in the army then, I was drafted in the army. And I was stationed in the South. And I was friends with a couple African-American kids who were also drafted. And we were in uniform and we were in this bar, we walked into this club. I forget where it was – and dead silence. I was like the only white face in the crowd. And the bartender said you better get out of here kid because I don’t think you’ll be welcomed, you know? But I was naive enough to just be able to walk in. Now, conversely during that same period of time audiences were segregated. When I first went to Richmond, Virginia, I wanted to see the ballet theatre from New York, they were performing. And the audience, the African-Americans were up in the balcony in the right side of the theater and they were dressed to the nines. I mean, it was just such a paradox for me. You know, and they were dignified, they were middle-class black people, teachers, so on. And I thought man, I would love to have them as neighbors, you know? Just beautiful people.

[00:12:10]

Joe: So, the nation being the way that it was at the time, how did that effect your paradigm traveling with them? I know you were close with Nina Simone, you took some bus trips. Were you slow to be trusted? Or did you feel like you just connected in a way completely outside of that?

Herb: I was trusted almost right away because I was paying attention to the musicians. I wasn’t just listening to their music, I was talking with them, hanging out with them, smoking a little dope with them, you know? It was an experience that I was able to recreate when I moved to Florida and joined the St. Pete NAACP branch, in which it was so different from what I was experiencing as a new resident of St. Petersburg. I mean, my goodness.

Joe: Different in what way?

Herb: Well, different in things were going on in the city regarding wages, regarding employment, which were not altogether known by the majority of people. Central Avenue as you may know was the dividing line. Whites lived in the South part of town – And I mean, blacks lived on the South side. And so it almost branded you if you said that you lived South, you know, First Avenue South, 34 Street South. So, it affected me and it affected the way that I look at people.

Joe: But you had a sensitivity to prejudice from your earliest days.

Herb: Oh yeah, it just didn’t come out of the blue. I mean, my parents were programmed out of the Ukraine, they came to America as refugees. I’m a first-generation American.

[00:14:03]

Joe: You tell a story of when you were first string quarter back went down on your high school football team and there was an African-American and yourself and the coach decided to put the African-American in to play but asked you to choose the play.

Herb: Yeah, well that was wonderful on one hand because it sort of substantiated me as a player, but on the other hand it was a totally racist thing for him to do. And so you begin to wake up, it was a little slow for me, but I woke up. And what I woke up to was something that I didn’t want to be a part of. So, I did what I had to do photographically to bring myself and others together. I’ve always seen my role as being a visual historian with a edge for disruption.

Joe: And when one looks at your full body of work that’s clear you’ve gotten arguably most of your commercial success and fame around the jazz work, how does that sit with you? Obviously, jazz was a real blessing for you, do you feel to some extent it pigeonholed you at all? Or were you just wholly grateful for it?

Herb: Oh no, I loved what I was doing. I have no regrets about leaving the jazz world when I had the opportunity to work in a summer hill type school for 13 years. And it was just a glorious time. It was the beat generation, it was The Beatles, and again, they were on the edge, these were young kids. I mean, Bob Dylan who was 24 years old, I have great stories about him and me.

Joe: I would love to hear one.

[00:15:56]

Herb: Well, it’s more sad then anything else when I was so involved in the jazz world, Bob Dylan was a block away at one of the coffee houses in New York and I didn’t go down, I just stayed. So, I never did meet him until years and years later. And I told him the story it was pretty funny.

Joe: So, there’s a lot of mythology in there. I was a beat fan myself, and imagined Ginsburg showing up to watch Dylan play in one of those little coffee houses in Soho or wherever. So, understanding what a part of history you were and understanding that through those images that’s how history largely gets made, how did mythology and place making shape your career and story-telling out of that time?

Herb: Not so much. I was a working artist. And instead of using paintbrushes I used light. You know, somebody asked Gene Smith if he used available light as opposed to studio light, and Gene said, “I’ll use any light that’s available.” That’s what it is for us. I mean, the way that light is falling on your face it’s kind of almost sinister.

Joe: Sinister?

Herb: [Chuckle] Yeah.

Joe: Pick a different adjective Herb, come on, how about angelic? [Chuckle] You know, you had an interesting front row seat to some of the personalities, specifically in jazz. One of the, we’ll say enigmas, was Miles Davis. And I think you used a quote where you say you take your hat off – Or you quoted somebody else saying they would take their hat off to the artist and put it back on.

Herb: Yeah, Toscanini.

Joe: Toscanini, yes, thank you.

Herb: Yeah.

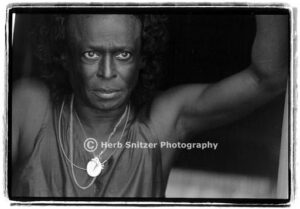

Joe: What’s the scoop on Miles? Was he a tortured artist? Was he angry?

[00:17:54]

Herb: Well, he tried to come off as being very hurt, and very deprived. He came out of a middle class environment in East St. Louis, his father was a dentist. He went to the right schools, I mean. And somewhere along the line he became a different person. My theory is that he was growing up at the same time that Clifford Brown was playing and Miles grabbed all of the attention. And what happened is Clifford was killed on the Pennsylvania Highway. He was going for a gig and it was snowing and sleeting and he got into an awful crash which killed him and I think one of his other players. And Miles knew this, obviously we all knew it. If Clifford had lived, here’s a young man who had five CDs or five records before he was 25 years old. I mean, it’s just an outstanding creative young man, lost to history in a way. And Miles knew that if Clifford had continued to play that people would be talking about Clifford Brown and not Miles Davis. That’s a pretty strong statement to make, like who am I to say Miles Davis is a terrible player, he wasn’t, but he was tortured and not very kind to women.

Joe: Do you attribute his middle-class upbringing to an insecurity around his authenticity to be part of that group? Or was it just entitled? Or was it really just baked into his personality?

Herb: No, I just think Miles felt entitled.

Joe: Entitled.

Herb: Yeah, he was a great player, can’t take anything away from him, he’s a great player. And I met him in 1960, that’s 60 years ago at the Apollo Theatre, the great Apollo Theatre in Harlem.

Joe: Did you feel like it got worse or better as he got more successful, had more money.

Herb: As a person?

Joe: As a person.

[00:20:08]

Herb: Oh yeah. I was living in Cambridge and the Boston Globe Jazz Festival was organized by George Wein, the producer. So, we are both at the theatre in Boston and Freddy – and I forget his last name, the producer of the Boston Globe Jazz Festival – said to me, “Miles doesn’t want you backstage.”

Joe: You specifically?

Herb: Yes, specifically. So, I said, “Well, what’s he going to do if I’m backstage, hit me?” You know, I’m a little guy, you know? So, I’m backstage because that’s where I wanted to be to do what I needed to do.

Joe: Right.

Herb: And Miles is facing the audience. So, I’m facing Miles’ back. I must have made a noise or something but he looked back and he takes his sunglasses and goes like this and I thought terrific, I got what I want and let’s see if I can get out of here in one piece. And Miles glaring at me, he knew me for 30 years for goodness sake. He just glared at me and I just stood my ground and looked back at him figuring what’s he going to do? Come onstage? Make a scene? So, that gave me a terrific image.

Joe: Yeah, it sounds like it.

Herb: Yeah.

Joe: Intensity.

Herb: Very intense.

Joe: You know, that seems aggressive for him to single you out and to say that.

Herb: No, all photographers. He didn’t want any photographers backstage.

Joe: Got it.

Herb: And there weren’t that many to begin with in those days. It’s not like today. So, if there were three of us back there the other two guys took off.

Joe: Right, so you got the only shot.

Herb: I got the only image of that time, yeah.

Joe: And how did that play in the rest of the jazz community? Did the other musicians feel similarly about him as far as you could tell?

Herb: Yes, some did. I would rather not name names, but some did.

[00:22:16]

Joe: Sure. Let’s flip over to a sweeter personality. I think you said you were closest with Nina Simone?

Herb: Yeah, for a long time. She was a real true love so to speak. Yeah, I met her during a commercial assignment for Colpix Records, Columbia Records in those days. And they hired me to do a series of photographs on Nina. And I had never met her before, but we just hit it off. I mean, we just took to each other like a duck to water. I mean, it was just astounding. And I kept in touch with Nina for years. And then because I moved out of New York and was involved with this free school, I didn’t see her for quite a number of years, but then I was able to with contacts talk to the producer of the Baron Jazz Festival and he hired me for three years in a row to come to Switzerland to photograph.

Joe: That’s a good gig.

Herb: And one thing led to another and Nina and I got together again and just had a wonderful time. I didn’t buy into it, she was difficult, you talk about a difficult person. Nina was very difficult, but it never washed over me. She and I just had a great time.

Joe: So, at some point in your career you transitioned from working photographer type of gigs through sort of a few other iterations but ultimately ended up at a place where you are a known photographer who people collect your work. You have a website, you know, you do limited addition prints. So, talk about how that grew in you and that transitioned to the place that where you are now where your name has a great value in the photographic community and how that sort of sprouted in your life.

[00:24:21]

Herb: Well, it wasn’t so much an either or. While I was doing the jazz, I was a documentary Life photographer. I was having other assignments rather than just the jazz, Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Betty Davis, Tennessee Williams. These are not jazz people, but they were assignments from the New York Times. And my photography was my life. I was consumed with making photographs. I just was so fascinated, so taken aback by what I considered magical moments that it just kept me going. I mean, I would carry my camera around all of the time. And we did that, that was part of being a documentary photographer in those days. You were privy to other photographers who were doing the same thing. And when we would meet each other we’d talk about things and so on. It wasn’t so isolating. The darkroom was isolating, which I love. But I also enjoyed the idea of just walking the streets of New York.

Joe: Right. So, when did you decide to start publishing books, and selling prints, and going down that road?

[00:25:44]

Herb: Well, almost from the beginning. It just was almost a fluke. I knew Nat Hentoff, and Nat was a great writer, constitutional writer for the New York Times. And I said to him I’ve done a book on Central Park. And what I would like to do is meet an editor here in New York who would understand my images which were very poetic. And he gave me the name of Emile Capouya, who by the way his son lives here. And when I met his son I said to him I said, “Are you related to Emile Capouya?” And he said he was my father. I lost it at that time. I didn’t know what to say. I was just so overwhelmed with feelings because Emile gave me my first break as far as books. He hired me to photograph a radical school in England. In which I then flew to England and photographed this school for many months. And life just flowed, it was really one thing led to another which led to another.

Joe: Right, but now you have a successful business. You command Good Bunny for your prints. And so I’m just really curious if that’s the – Not for all photographers, but obviously many photographers wouldn’t mind if that happened or they got to a point where they had the name recognition and the quality to have a career as long as you’ve had, but then also get to a point where there is a collectability around your work.

Herb: Well, you live long enough I guess that’s what happens. Yeah, don’t die. [Chuckle]

Joe: So that doesn’t move the needle for you at all? That sort of recognition knowing that you’ll go down in history as a really lauded collectable photographer? I think that’s a fantastic achievement.

Herb: Yeah, I guess so. I don’t make much of it when people come and look. Not now, I mean, this virus has brought me to a standstill at this point.

Joe: And when you go down that road, I’m curious about even things like pricing prints. And, you know, I find art pricing fascinating. I feel like you could take a piece and maybe put it on the wrong gallery or the wrong store in Central Avenue and price it at $500 and it would never sell, and you could take the same piece of art and put it on the right gallery in Miami and put $50,000 on it and it might sell in two hours.

[00:28:19]

Herb: Yeah.

Joe: It’s a strange psychology.

Herb: It’s a crapshoot. I mean, especially now that photography has been recognized by the kings, the people who matter so as I say it. It’s like this portfolio that I have, this jazz portfolio, 75 issues of the portfolio, 10 prints. 10 beautifully produced prints. And when we started out Gus Kayafas, the producer, he was either giving them to certain people in the photographic world or selling them for $15,000 for the 10 prints. Right now today it’s priced at $10,000 now. Same prints. I didn’t do anything other then supply the negative to Gus and he got the producers and all involved.

Joe: Are you saying that he was strategic in who he gave those to, to sort of see the interest?

Herb: Oh yeah, it became a marketing tool. And some of these guys demanded very high money for them. Like I have a portfolio by one of the great 20th Century photographers. I was a very close friend of him. And I had this portfolio that he produced only five copies, I had number one. It’s now worth about $50,000, the portfolio. But when I got it, it was no where near that. So, it’s just like any other demand that became a commodity.

[00:30:04]

Joe: What sort of persona do you think is the biggest driver of that – is the strategic buyer who sets the trends? Is it that broker in the middle?

Herb: No, the buyer. There were two men who collected photography. I mean, really, besides Alfred Stieglitz, who was the father of us all. With these two men, put a lot of money in politics and they are standing in the community and all of a sudden it broke lose. And then photography became a real expensive commodity.

Joe: And when you referred to the kings deemed is that who you were referring to?

Herb: Yeah, the people who really run the photographic galleries, the photographic shows, the articles on photography.

Joe: Right, make it a market.

Herb: Yeah, it’s the market. And my experience with that is not very good.

Joe: Why not?

Herb: Well, in their terms I lived down here. I’m not interacting socially, I’m not buying, going out and spending money buying gifts and all this kind of stuff that photographers thought that they needed to do. I never did.

Joe: Do you feel like the internet and the connectiveness of the world has changed that at all?

Herb: Yeah, I work directly through the computer. And we’re not talking about millions of dollars here, although I do have an archive which I’ve been trying to place, which is now valued at 1.5 million dollars.

Joe: Wow, so tell me a little bit about the archive.

Herb: Well, it’s all my work. It’sn100,000 negatives, thousand prints, I have it all up here.

Joe: Do you feel like the reproducibility of photographs made it tougher sledding then say an oil painting?

[00:32:00]

Herb: Well, that’s always been the argument with photography. But the art world can produce prints, can produce other ways to make an image. I consider each print that I make an original print. It’s not an afterthought, it’s an originally print. And I limit prints. And so, for me, it’s just part and parcel of the art world. I started off as a painter. I painted for years. I found that I was better taking pictures then painting. So, that’s where we are.

Joe: You know, before we move, I know we talked about the jazz musicians and the experiences you had with racism throughout your life or observed, and felt, and felt a need to take pictures that showed your feelings about it. So, I wanted to spend a little more time on that because I think it’s a very important topic. Can you talk a little bit about how the jazz musicians struggled, and the people who you worked with at that time how their livelihoods, careers, and sort of beings were affected?

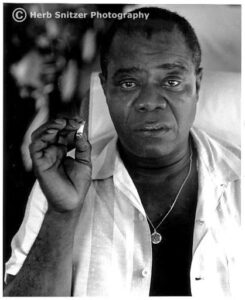

Herb: Sure. Louis Armstrong, on that bureau, was made on a bus tour when I took with Pops and his band. Leaving his home in Fleshing getting onto whatever that road is. Pops had to go to the bathroom. It was a bus with no air conditioning and very few amenities. And so, we stopped the bus, Pops got out, went into this dinner and we were told to just wait. And he comes out looking so angry. This is in Connecticut now. He was refused to use the bathroom facilities. And the only explanation I came up with is because he was Black. And I never forgot the look. As a matter of fact I made a couple of photographs of him walking across the street.

[00:34:23]

And he already was, you know, Pops was a little guy, he was like my size if you could believe it, he could blow a horn. And he is not recognizable by many people, he had on shorts, he had his shirt open, it was a hot June day. So, that’s one example. Coming back from Tanglewood at 2 in the morning we stopped at a diner, at an all-night diner, and here is Louis Armstrong, the most recognizable voice in the world sitting in this diner at two o’clock in the morning having a cup of coffee. But before he got there the road manager went into the diner to make sure that it would be OK if Lewis Armstrong came in and got a cup of coffee. Well, they were thrilled, but it showed me that they were also very, very cautious because you never know like today. You never know whether some crazy white supremacist would pull a gun. You know, in those days it was just as volatile. So, when the road manager said it was OK, all the musicians, Trummy Young, Mart Herbert, they all came into the diner and we had a party, we had a party going. The guy who owned the diner was thrilled, you know, the great Louis Armstrong. But you never knew what was going to happen.

[00:36:01]

Joe: And how about St. Petersburg specifically? You’ve been here for many decades, you live South of Central Avenue Lakewood Estates. And how do you feel St. Petersburg has done in your time here with regards to equity?

Herb: Oh, it’s changed dramatically. Just dramatically. There were no Jewish real estate people downtown, this is the white world now downtown. You wanted to see where they all were, Clearwater. The doctors went to Clearwater. It was segregated. And that’s gone now. I mean, I like to think that we’ve grown up, we’ve become a bigger city. And it had, from an art standpoint when I first moved here I couldn’t believe what I was moving into.

Joe: You’ve been a big part of that.

Herb: Yeah, so I got involved with Salt Creek Artworks and we kept it going for many years. And it left a mark.

Joe: So, as you’re now moving into the, we’ll say the second half of your career?

Herb: Oh, this is the third. [Chuckle]

Joe: The third half, OK.

Herb: You know, I struggle with Parkinson’s, which is no fun. But I keep making photographs. I keep photographing and I hope for the best.

Joe: Wonderful. Thank you.

Herb: Thank you.

End of transcript – [00:37:26]